Twenty Seventh Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

When hosting a party, it’s hard not to take a person’s absence personally, especially if the reason goes unmentioned. Without an RSVP, the host is left to assume the worst. Did the person die on the way over? Or worse still, did they have better things to do and never really liked you in the first place? Such is the case, it seems, for us clergy who are wondering where some of the pre-pandemic stalwarts have gone. After almost a year of reopening our local churches with half a year of lifting of SOPs restricting church attendance, we are still not back to full capacity. Where did the rest of the people go? Why haven’t they gone back to church? Fear of infection could be one legitimate reason, but I think the most common reason is that many no longer feel a sense of urgency or need to come to church.

The English philosopher Alfred Whitehead once said, “Apart from religion, expressed in ways generally intelligible, populations sink into the apathetic task of daily survival, with minor alleviations.” These past two years for most of us have been exactly that - an “apathetic task of daily survival, with minor alleviations.” Religion no longer seems relevant nor does it alleviate our daily boredom.

What do we do when apathy sets into our faith life? The problem and remedy seem to be addressed by this week’s readings. Faith is the motif in each reading. The seldom-referenced prophet Habakkuk had grown frustrated with the lack of faith evidenced in his people's behaviour and responsiveness to God. They had grown spiritually slothful and now the prophet himself is tempted to follow suit. But God assures him, however, that his prayers are heard, and God never disappoints. Perseverance would be the first remedy to spiritual apathy. We should keep praying, even when we don’t feel like it. We should keep going for mass and confession, even when we seem to get nothing out of it. As the Lord assured Habakkuk, “if it comes slowly wait, for come it will, without fail,” because “the upright man will live by his faithfulness.”

Similarly in the gospel, when the disciples learned more about the demands of discipleship, they feared they did not have the faith to meet the challenges that came with it. The heaviness of discipleship weights down on them. To that end, they beg, “increase our faith,” a frank admission of their profound lack. But the problem is that faith is not quantifiable. Nevertheless, it is the power that inspires us, helps us to persevere, enables us to struggle and not lose heart, and keeps us ever mindful of God’s abiding presence. That is why our Lord uses the images of the mustard seed and the mulberry tree to graphically illustrate the power of faith, even the tiniest spark of it, can move the unmovable and accomplish what appears to be impossible.

At first glance, it might appear that the Lord was being sarcastic. But this was not His intention. In fact, He clearly knew and understood their weaknesses, but He also wanted them to understand that even a little faith goes a long way. His parable about the servant seems to say that faith is not a reward for the spiritually proficient; rather, faith is the requisite condition for every disciple. And when we have faith, we are merely doing our job as disciples and should seek no reward.

Yes, even a little faith can go a long way. Faith begets faith. True faith is like a small snowball poised at the top of a long slope, waiting to be pushed so it might then grow as it picks up speed. But that snowball is always first formed and moved by God. Faith is first and foremost a gift from God. But faith is also a response. When we respond in obedience to God and His gift, faith grows. This is because faith is also a habit, a power or capacity that gets stronger when it is exercised and atrophies when it is not. So, faith is like a spiritual muscle. The way you develop faith is, to exercise it regularly and to do so against ever increasing resistance. Don’t expect faith to get easier. It necessarily gets harder because the only way faith grows is to be challenged. If you ask for faith, know that this means giving the Lord permission to put more weight on the bar. If we wish to grow in faith, we must be ready to go against the grain, practise discipline, and do the hard work. For, as St. Paul says, “God did not give us a spirit of timidity, but a spirit of power and love and self-control (2 Timothy 1:8).”

That brings us full circle back to St Paul in the second reading and the wisdom he shared with his friend and colleague, Timothy. As he reminded Timothy, our faith must be tended, stirred and fed like a flame. Our Christian faith can be likened to hot coals which would make a fire when fanned but become cold and useless if left alone. Many of us Catholics were baptised as infants, thus becoming Christians before we knew anything at all. Many of us grew up without properly tending that initial spark of faith that was given to us at baptism or we had allowed the pressures and distractions of life to reduce our faith to cold ashes. The result being so many have left the faith of our childhood, the faith of our parents, believing this is no longer relevant.

How do we fan into a flame God's gift of faith that has been kindled within us? Fanning our faith into a flame implies that we respond to the grace of God in us. It is achieved through daily communion with God in prayer, taking time to prayerfully study His Word and frequenting the Sacraments of Penance and the Holy Eucharist. It means reading good spiritual books and attending good formations to deepen our faith. Being immersed in a faith community, like our BEC, is essential for our growth in faith. As we open our hearts to God in these ways, He strengthens our faith, allowing the seed of faith planted in us to blossom. But when we cease doing these things, we would soon find our enthusiasm for anything spiritual diminishing. When we cease committing ourselves to these spiritual exercises, we will soon see the fire within us become smouldering embers of a dying faith.

If some of us can recognise the value of a booster shot of vaccine to increase our immunity, we can also understand that most of us need an occasional shot in the arm to keep our faith strong and vibrant. But this does not mean that we should be constantly searching for extraordinary experiences that give us an emotional high. Growth in friendship with God does not happen only in the special, uplifting moments. It is through our daily efforts to be faithful to God, to live our faith in the everyday, with the help of the Sacraments, that our bond with God is strengthened.

Yes, we need to fan into flame the gift of faith God has given us. But for it to really catch fire, we need to step out in faith. Every step of faith that we take is like the oxygen added to the fire to keep it blazing! Our effort, feeble though it may seem to us (like a tiny insignificant mustard seed), works like a bellows blowing air onto the fire until it is a blazing bonfire. So, let us fan the flame of the Spirit. Let His fire burn away all doubt and hesitation, all sloth and apathy, so that you can become a beacon of faith, hope, and love for the people around you. And if you know of someone whose flame of faith has almost gone out or has faded entirely, give it a gust of new life by encouraging them to return to Church and be involved once again in the life of the community of faith. As Pope Francis constantly reminds us – what the Church needs more than ever today, are joyful witnesses full of enthusiasm rather than someone who had just walked out of a funeral.

Wednesday, September 28, 2022

Monday, September 19, 2022

Get off your comfy couch!

Twenty Sixth Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

Having gone back to pre-pandemic full capacity, many parishes are awkwardly still witnessing relatively low attendance at Masses. What could be the cause of this? In 2020 and 2021, as our country navigated between complete lockdowns and impossibly stringent SOPs governing public gatherings when some activities were allowed, many of our churches discontinued physical attendance at Masses for long stretches and substituted them with online services. According to the best research, it takes 60–70 days to form a new habit, and we had months of lockdowns and two years of restrictions! That’s plenty of time to form a new habit.

In today’s first reading, the prophet Amos confronts the people of Israel for their spiritual lethargy. He accused them of “lying on ivory beds and sprawling on their divans” while dining on their fatted lambs. He was practically telling them to get off their comfy couches, cease living a sedentary life seated in front of their televisions while gorging on junk food, while ignoring all the critical things happening around them. Apathy or indifference to the cries and plight of the poor, the marginalised, victims of oppression and injustice had become a new habit which they found hard to abandon.

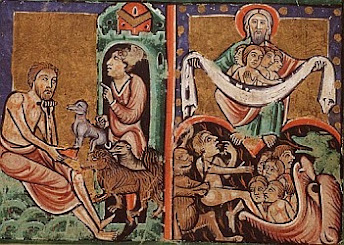

We see a vivid illustration of this in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, in the gospel. The rich man who enjoyed life was condemned to hell at the end of the story whereas Lazarus who suffered in this life, ended up in heaven. The parable is troubling not only for its mention of hell but because the rich man should even end up in hell, though he is not depicted as a horrible person. In fact, the gospel never states that the rich man mistreated poor Lazarus. There is no mention of him acquiring his wealth through unjust means. The point of this parable is not that the rich will be damned and the poor will be saved. Neither is the point of this parable describing a capricious God who likes sending poor souls to hell for the slightest infraction. The problem with the rich man, if you could consider it a problem, is that he was without suffering - he had no inclination of suffering because he had all the luxuries which money could buy. For this reason, he couldn’t feel the pain and the suffering of the beggar Lazarus.

What did the rich man do that was so horrible that he should deserve such a terrible fate as hell? It was simply his apathy. Apathy is indifference habitualised. Examining the Greek root of the word would give us a better understanding of this sin. Apathy comes from two Greek words - “a” which denotes the absence of something, “without”; and “pathos” which means suffering. Therefore, the apathetic person is one who does not know or feel the suffering of another, as opposed to an emphatic person, someone who experiences and feels the suffering of the other.

This was the “crime” of the rich man - he was enclosed in his safe little world of personal enjoyment, insulated by his wealth and comfortable life. Lazarus, therefore, was not treated as a part of suffering humanity but just a part of the landscape. In a word, the rich man was indifferent, and clueless: Indifferent to Lazarus’ plight, indifferent to his hunger, indifferent and clueless to his needs. They were the neighbours who never met.

The indifference which blinded the rich man to the needs of Lazarus and others in this life is a foretaste of what is to come - the chasm that separates heaven from hell, a chasm wide and unbridgeable. There is no passing between the two, ever. In life, a big chasm had opened up between the rich man and Lazarus due to the former’s apathy. Lazarus never showed up on the rich man’s radar. In death, this chasm has grown infinite – in the words of Father Abraham, a ‘great gulf’ separates the minions of hell from the minions of heaven. The chasm which the rich man maintained through his indifference in life had ultimately separated him from God in death. Now, it’s the rich man’s turn to drop off God’s radar. Indifference does not only spell human tragedy, but it also means the lost of beatitude, the lost of salvation.

An apathetic person will not exert any effort to make a difference. He either sees no need to do so or feels so overwhelmed by the problem that he believes that whatever he does will make little to no dent in the issue. He tells himself, “What’s the point?” “Is this my problem?” Or “how does this even concern me?” He will simply sit back and watch events unfold. Unfortunately, this is all that is needed to make one’s journey to hell certain. In the words of the philosopher Edmund Burke, “All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.”

Apathy may seem as insignificant as a tiny crack but it eventually morphs into a great chasm that comes between heaven and hell. Apathy is what makes us ignore the message of the prophets and pass generations and even makes us turn our backs on the One who died and is now risen from the dead. In fact, apathy is what killed the Lord Jesus Christ. Both the fearful Pilate and the jealous High Priests would not have been able to put Jesus to death except for the thousands of people who didn't show up for the crucifixion. They didn't want Jesus dead or alive. They just didn't care. Apathy permitted Hitler to kill six million Jews, and abortion clinics to kill many more millions of babies. Apathy lets thousands die each day of starvation, and billions live each day without knowing Jesus.

At the end of the parable, the rich man asked Abraham to send Lazarus back to earth to warn his brothers to repent so that they would never join him in hell. Abraham told the rich man that if his brothers did not believe in Scripture, neither would they believe a messenger, even if he came straight from heaven. Looks like man’s indifference to his neighbour is finally unmasked – it is merely a cover, a symptom of man’s indifference to God.

Both Amos and our Lord are calling us to get off our comfy couches and to get going. There is no room for couch potato Christians. In fact, being Christian means that we must change our apathy into empathy, we cannot cut ourselves from others because as St Paul reminds us: “If one member suffers, all the members suffer with it.” In his personal letter to Timothy which we heard in our second reading, St Paul outlines what is required of us: “As a man dedicated to God, you must aim to be saintly and religious, filled with faith and love, patient and gentle. Fight the good fight of the faith and win for yourself the eternal life to which you were called when you made your profession and spoke up for the truth in front of many witnesses.”

Having gone back to pre-pandemic full capacity, many parishes are awkwardly still witnessing relatively low attendance at Masses. What could be the cause of this? In 2020 and 2021, as our country navigated between complete lockdowns and impossibly stringent SOPs governing public gatherings when some activities were allowed, many of our churches discontinued physical attendance at Masses for long stretches and substituted them with online services. According to the best research, it takes 60–70 days to form a new habit, and we had months of lockdowns and two years of restrictions! That’s plenty of time to form a new habit.

In today’s first reading, the prophet Amos confronts the people of Israel for their spiritual lethargy. He accused them of “lying on ivory beds and sprawling on their divans” while dining on their fatted lambs. He was practically telling them to get off their comfy couches, cease living a sedentary life seated in front of their televisions while gorging on junk food, while ignoring all the critical things happening around them. Apathy or indifference to the cries and plight of the poor, the marginalised, victims of oppression and injustice had become a new habit which they found hard to abandon.

We see a vivid illustration of this in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, in the gospel. The rich man who enjoyed life was condemned to hell at the end of the story whereas Lazarus who suffered in this life, ended up in heaven. The parable is troubling not only for its mention of hell but because the rich man should even end up in hell, though he is not depicted as a horrible person. In fact, the gospel never states that the rich man mistreated poor Lazarus. There is no mention of him acquiring his wealth through unjust means. The point of this parable is not that the rich will be damned and the poor will be saved. Neither is the point of this parable describing a capricious God who likes sending poor souls to hell for the slightest infraction. The problem with the rich man, if you could consider it a problem, is that he was without suffering - he had no inclination of suffering because he had all the luxuries which money could buy. For this reason, he couldn’t feel the pain and the suffering of the beggar Lazarus.

What did the rich man do that was so horrible that he should deserve such a terrible fate as hell? It was simply his apathy. Apathy is indifference habitualised. Examining the Greek root of the word would give us a better understanding of this sin. Apathy comes from two Greek words - “a” which denotes the absence of something, “without”; and “pathos” which means suffering. Therefore, the apathetic person is one who does not know or feel the suffering of another, as opposed to an emphatic person, someone who experiences and feels the suffering of the other.

This was the “crime” of the rich man - he was enclosed in his safe little world of personal enjoyment, insulated by his wealth and comfortable life. Lazarus, therefore, was not treated as a part of suffering humanity but just a part of the landscape. In a word, the rich man was indifferent, and clueless: Indifferent to Lazarus’ plight, indifferent to his hunger, indifferent and clueless to his needs. They were the neighbours who never met.

The indifference which blinded the rich man to the needs of Lazarus and others in this life is a foretaste of what is to come - the chasm that separates heaven from hell, a chasm wide and unbridgeable. There is no passing between the two, ever. In life, a big chasm had opened up between the rich man and Lazarus due to the former’s apathy. Lazarus never showed up on the rich man’s radar. In death, this chasm has grown infinite – in the words of Father Abraham, a ‘great gulf’ separates the minions of hell from the minions of heaven. The chasm which the rich man maintained through his indifference in life had ultimately separated him from God in death. Now, it’s the rich man’s turn to drop off God’s radar. Indifference does not only spell human tragedy, but it also means the lost of beatitude, the lost of salvation.

An apathetic person will not exert any effort to make a difference. He either sees no need to do so or feels so overwhelmed by the problem that he believes that whatever he does will make little to no dent in the issue. He tells himself, “What’s the point?” “Is this my problem?” Or “how does this even concern me?” He will simply sit back and watch events unfold. Unfortunately, this is all that is needed to make one’s journey to hell certain. In the words of the philosopher Edmund Burke, “All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.”

Apathy may seem as insignificant as a tiny crack but it eventually morphs into a great chasm that comes between heaven and hell. Apathy is what makes us ignore the message of the prophets and pass generations and even makes us turn our backs on the One who died and is now risen from the dead. In fact, apathy is what killed the Lord Jesus Christ. Both the fearful Pilate and the jealous High Priests would not have been able to put Jesus to death except for the thousands of people who didn't show up for the crucifixion. They didn't want Jesus dead or alive. They just didn't care. Apathy permitted Hitler to kill six million Jews, and abortion clinics to kill many more millions of babies. Apathy lets thousands die each day of starvation, and billions live each day without knowing Jesus.

At the end of the parable, the rich man asked Abraham to send Lazarus back to earth to warn his brothers to repent so that they would never join him in hell. Abraham told the rich man that if his brothers did not believe in Scripture, neither would they believe a messenger, even if he came straight from heaven. Looks like man’s indifference to his neighbour is finally unmasked – it is merely a cover, a symptom of man’s indifference to God.

Both Amos and our Lord are calling us to get off our comfy couches and to get going. There is no room for couch potato Christians. In fact, being Christian means that we must change our apathy into empathy, we cannot cut ourselves from others because as St Paul reminds us: “If one member suffers, all the members suffer with it.” In his personal letter to Timothy which we heard in our second reading, St Paul outlines what is required of us: “As a man dedicated to God, you must aim to be saintly and religious, filled with faith and love, patient and gentle. Fight the good fight of the faith and win for yourself the eternal life to which you were called when you made your profession and spoke up for the truth in front of many witnesses.”

Wednesday, September 14, 2022

Seeing beyond the veil

Twenty Fifth Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

All three readings, if read separately, would have had their own respective appeal and would have seemed reasonable had each been judged by their own internal logic. The problem is when we juxtapose them, as the lectionary does this week, and attempt to reconcile the seemingly divergent messages, we may end up having to do theological acrobatic somersaults. Or at least it would seem to be so.

In the first reading, the prophet Amos condemns both the political and religious leaders for the crime of social injustice and their part in oppressing the poor and the powerless. In the second reading, St Paul writes to Timothy and tells him to pray for civil authorities, including those who are corrupt and who are oppressing Christians, for as he reminds Timothy, God “wants everyone to be saved and reach full knowledge of the truth.” So far, so good. There is a recognition of mutuality and the need for checks-and-balances between the two spheres of religion and civil society. On the one hand, we are called to play a prophetic role with regards to civil authorities and call them out for their misdeeds whenever it is necessary. On the other hand, we should also not neglect our duty in praying for them, for it is the will of God that all be saved.

But the gospel seems to cross the line by providing us with the strangest advice on how we should interact and relate with civil society. In this pericope, a steward appears to be commended for dishonest behaviour and made an example for Jesus' disciples. Does it sound like the Lord is asking us to emulate the values of secular society, including buying friends with money and favours? If this was true, then a former Prime Minister of a certain county should not have been tried and sentenced to imprisonment. He should have been celebrated for his astuteness. Of course, none of us would come to this conclusion. This certainly takes the cake when it comes to the ludicrous. It is no wonder that many Christians find this parable a source of embarrassment. How do we reconcile this with the rest of the Bible and our readings for today?

In this fairly simple, if somewhat unorthodox, parable, there is a major reversal of sorts. In most of the Lord’s parables, the main protagonist is either a representative of God, Christ, or some other positive character. In this parable, the characters are all wicked – the steward and the man whose possessions he manages are both unsavoury characters. This should alert us to the fact that Jesus is not exhorting us to emulate the behaviour of the characters, but is trying to expound on a larger principle. Certainly, the Lord wants His followers to be just, righteous, magnanimous, and generous, unlike the main protagonist in the parable. But what does this dishonest steward have to offer us as a point of learning? The gospel notes that the Lord commends him for his “astuteness”.

The dishonest steward is commended not for mishandling his master's wealth, but for his shrewd provision in averting personal disaster and in securing his future livelihood. The original meaning of "astuteness" is "foresight" – the ability to see ahead and anticipate what’s in store in the future. An astute person, therefore, is one who grasps a critical situation with resolution, foresight, and the determination to avoid serious loss or disaster.

If foresight is the true measure of intelligence, a Christian must be ‘super’ intelligent since his foresight extends beyond this temporal plane, it penetrates the veil of death and catches a glimpse of the eternal vision of glory. As the dishonest steward responded decisively to the crisis of his dismissal due to his worldly foresight, so Christians are to respond decisively in the face of their own analogous crisis with heavenly foresight. The crisis may come in the form of the brevity and uncertainty of life or the ever-present prospect of death; for others it is the eschatological crisis occasioned by the coming of the Kingdom of God in the person and ministry of Jesus. It follows that people who are just wholly invested in their present lives, seeking to make themselves rich, famous and popular, but giving little to no thought about the future, about what happens in the afterlife, will be shown to have been the most foolish.

Our Lord is concerned that we avert spiritual crisis and personal disaster through the exercise of faith, foresight and compassion. If Christians would only expend as much foresight and energy to spiritual matters which have eternal consequences as much as they do to earthly matters which have temporal consequences, then they would be truly better off, both in this life and in the age to come. St Ambrose provides us with a spiritual wisdom that can only be perceived through the use of heavenly foresight: “The bosoms of the poor, the houses of widows, the mouths of children are the barns which last forever.” In other words, true wealth consists not in what we keep but in what we give away. Wholesomeness is measured by the extent of how we live our lives for the glory of God, and not for ourselves or for things.

Today, many modern persons see no need for us to pray for them and neither do they believe that we are in any position to judge them. In fact, they often view the Church as anachronistic and Christians as unintelligent, superstitious and irrational dimwits. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Although no empirical research will be able to show this, but the personal experiences of many will testify to the fact that the most intelligent thing an intelligent human being can do is to turn to God, not away from Him. The faith and lives of the heroes and heroines in both scriptures and the history of our Church testify to this. We may have found ways and means of averting or resolving various medical, economic and social crises, but only God is capable of helping us avert the greatest crisis of all - the loss of Eternal Life. It is rightly said that wise men still seek Him, wiser men find Him, and the wisest come to worship Him. Anyone who ignores this truth would be a fool.

All three readings, if read separately, would have had their own respective appeal and would have seemed reasonable had each been judged by their own internal logic. The problem is when we juxtapose them, as the lectionary does this week, and attempt to reconcile the seemingly divergent messages, we may end up having to do theological acrobatic somersaults. Or at least it would seem to be so.

In the first reading, the prophet Amos condemns both the political and religious leaders for the crime of social injustice and their part in oppressing the poor and the powerless. In the second reading, St Paul writes to Timothy and tells him to pray for civil authorities, including those who are corrupt and who are oppressing Christians, for as he reminds Timothy, God “wants everyone to be saved and reach full knowledge of the truth.” So far, so good. There is a recognition of mutuality and the need for checks-and-balances between the two spheres of religion and civil society. On the one hand, we are called to play a prophetic role with regards to civil authorities and call them out for their misdeeds whenever it is necessary. On the other hand, we should also not neglect our duty in praying for them, for it is the will of God that all be saved.

But the gospel seems to cross the line by providing us with the strangest advice on how we should interact and relate with civil society. In this pericope, a steward appears to be commended for dishonest behaviour and made an example for Jesus' disciples. Does it sound like the Lord is asking us to emulate the values of secular society, including buying friends with money and favours? If this was true, then a former Prime Minister of a certain county should not have been tried and sentenced to imprisonment. He should have been celebrated for his astuteness. Of course, none of us would come to this conclusion. This certainly takes the cake when it comes to the ludicrous. It is no wonder that many Christians find this parable a source of embarrassment. How do we reconcile this with the rest of the Bible and our readings for today?

In this fairly simple, if somewhat unorthodox, parable, there is a major reversal of sorts. In most of the Lord’s parables, the main protagonist is either a representative of God, Christ, or some other positive character. In this parable, the characters are all wicked – the steward and the man whose possessions he manages are both unsavoury characters. This should alert us to the fact that Jesus is not exhorting us to emulate the behaviour of the characters, but is trying to expound on a larger principle. Certainly, the Lord wants His followers to be just, righteous, magnanimous, and generous, unlike the main protagonist in the parable. But what does this dishonest steward have to offer us as a point of learning? The gospel notes that the Lord commends him for his “astuteness”.

The dishonest steward is commended not for mishandling his master's wealth, but for his shrewd provision in averting personal disaster and in securing his future livelihood. The original meaning of "astuteness" is "foresight" – the ability to see ahead and anticipate what’s in store in the future. An astute person, therefore, is one who grasps a critical situation with resolution, foresight, and the determination to avoid serious loss or disaster.

If foresight is the true measure of intelligence, a Christian must be ‘super’ intelligent since his foresight extends beyond this temporal plane, it penetrates the veil of death and catches a glimpse of the eternal vision of glory. As the dishonest steward responded decisively to the crisis of his dismissal due to his worldly foresight, so Christians are to respond decisively in the face of their own analogous crisis with heavenly foresight. The crisis may come in the form of the brevity and uncertainty of life or the ever-present prospect of death; for others it is the eschatological crisis occasioned by the coming of the Kingdom of God in the person and ministry of Jesus. It follows that people who are just wholly invested in their present lives, seeking to make themselves rich, famous and popular, but giving little to no thought about the future, about what happens in the afterlife, will be shown to have been the most foolish.

Our Lord is concerned that we avert spiritual crisis and personal disaster through the exercise of faith, foresight and compassion. If Christians would only expend as much foresight and energy to spiritual matters which have eternal consequences as much as they do to earthly matters which have temporal consequences, then they would be truly better off, both in this life and in the age to come. St Ambrose provides us with a spiritual wisdom that can only be perceived through the use of heavenly foresight: “The bosoms of the poor, the houses of widows, the mouths of children are the barns which last forever.” In other words, true wealth consists not in what we keep but in what we give away. Wholesomeness is measured by the extent of how we live our lives for the glory of God, and not for ourselves or for things.

Today, many modern persons see no need for us to pray for them and neither do they believe that we are in any position to judge them. In fact, they often view the Church as anachronistic and Christians as unintelligent, superstitious and irrational dimwits. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Although no empirical research will be able to show this, but the personal experiences of many will testify to the fact that the most intelligent thing an intelligent human being can do is to turn to God, not away from Him. The faith and lives of the heroes and heroines in both scriptures and the history of our Church testify to this. We may have found ways and means of averting or resolving various medical, economic and social crises, but only God is capable of helping us avert the greatest crisis of all - the loss of Eternal Life. It is rightly said that wise men still seek Him, wiser men find Him, and the wisest come to worship Him. Anyone who ignores this truth would be a fool.

Monday, September 5, 2022

Coming to our senses

Twenty Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

Our lengthy passage provides us with three parables of lost-and-found scenarios. All three paint an unforgettable picture of the overflowing love and forgiveness of God. It opens with the one lost sheep, for which the owner scales hills and valleys, ravines and outcrops, until he reconnects it to the other ninety-nine. The passage continues with one lost coin for which the woman of the house does a thorough cleaning to find it. And our trilogy concludes with the story of the Prodigal Son. Perhaps our familiarity with the Parable of the Prodigal Son dulls our perception of just how radical this father’s love is.

Today, I would like to pay attention to the third and longest of the three parables. Its most common name is the Prodigal Son, but I would prefer to give it a title which follows the pattern of the earlier two stories. If the first two stories speak of a lost sheep and a lost coin, what we have here is a lost son. But the younger son wasn’t the only one lost. The ending of the story shows that his elder brother, who seems to have fulfilled his filial duties to their father, is equally lost, but with a big difference. There is no turning point in the elder son’s story.

I’m going to spare you another paraphrasing of an already lengthy but vividly told story with its many twists and turns. I would just wish to turn to the turning point in the story of the younger son, the wastrel who abandoned his duties at home, cursed his father to an early death, and lived a life of hedonistic excesses and debauchery. St Luke tells us that after having experienced a radical reversal in his fortunes and at the critical point when he had lost everything - his friends, his wealth and his dignity - “he came to his senses.” This is the moment of awareness, the long-awaited regret, the needed sorrow for his mistakes. It is matched by an overwhelming realisation of what he had lost - his father’s immeasurable benevolence shown even to lowly servants. He begins the long track home.

It is this point in the third parable which makes it unique among the set of three. I don’t think that the lost sheep in the first parable nor the inanimate and non-sentient coin in the second, could ever come to their senses. Only man is capable of doing this because only man possesses the freedom of intellect and will need to repent of his ways.

But let’s not be under the impression that “coming to his senses” meant that he had fully acknowledged his culpability and was now truly repentant. His reasoning was still quite self-serving: “How many of my father’s paid servants have more food than they want, and here am I dying of hunger!” Yes, there was an acknowledgment that he had made a miscalculated move. He thought he would be better off on his own without his father but now realises that even his father’s servants have it better than him. But this was short of a contrition for his past faults. Hidden within this selfish and self-centred logic, is also the uneasy acknowledgment of his father’s generosity - that the servants under his father enjoy a lifestyle better than they could ever deserve and would ever need. But such acknowledgment was the first step to his repentance.

We are then presented with another amazing fact that the father in this story, whom every reader now understands, refers to God the Heavenly Father. “Nowhere else,” remarked the theologian Hans von Balthasar, “does Jesus portray the Father in heaven more vitally, more plainly.” This father, or God whom he represents, has never given up hope on his wayward and ungrateful son. The son may have turned his back on his father, he may have wished his father dead, he may have squandered his inheritance which the father had given him, but now returns to a father who has never given up or written off or turned his back on his son.

Yes, we all need to come to our senses. We all need to recognise that life can never be good apart from God. We all need to acknowledge that God owes us nothing, whether by virtue of our birthright, as in the case of the younger son, or by earning it like the older son. God’s riches and our inheritance of Eternal Life can never be earned nor is it something we are entitled to. Because He loves us, God has lavishly poured out upon us His most precious treasure of all. As St John so beautifully puts it: “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” (John 3:16)

Our lengthy passage provides us with three parables of lost-and-found scenarios. All three paint an unforgettable picture of the overflowing love and forgiveness of God. It opens with the one lost sheep, for which the owner scales hills and valleys, ravines and outcrops, until he reconnects it to the other ninety-nine. The passage continues with one lost coin for which the woman of the house does a thorough cleaning to find it. And our trilogy concludes with the story of the Prodigal Son. Perhaps our familiarity with the Parable of the Prodigal Son dulls our perception of just how radical this father’s love is.

Today, I would like to pay attention to the third and longest of the three parables. Its most common name is the Prodigal Son, but I would prefer to give it a title which follows the pattern of the earlier two stories. If the first two stories speak of a lost sheep and a lost coin, what we have here is a lost son. But the younger son wasn’t the only one lost. The ending of the story shows that his elder brother, who seems to have fulfilled his filial duties to their father, is equally lost, but with a big difference. There is no turning point in the elder son’s story.

I’m going to spare you another paraphrasing of an already lengthy but vividly told story with its many twists and turns. I would just wish to turn to the turning point in the story of the younger son, the wastrel who abandoned his duties at home, cursed his father to an early death, and lived a life of hedonistic excesses and debauchery. St Luke tells us that after having experienced a radical reversal in his fortunes and at the critical point when he had lost everything - his friends, his wealth and his dignity - “he came to his senses.” This is the moment of awareness, the long-awaited regret, the needed sorrow for his mistakes. It is matched by an overwhelming realisation of what he had lost - his father’s immeasurable benevolence shown even to lowly servants. He begins the long track home.

It is this point in the third parable which makes it unique among the set of three. I don’t think that the lost sheep in the first parable nor the inanimate and non-sentient coin in the second, could ever come to their senses. Only man is capable of doing this because only man possesses the freedom of intellect and will need to repent of his ways.

But let’s not be under the impression that “coming to his senses” meant that he had fully acknowledged his culpability and was now truly repentant. His reasoning was still quite self-serving: “How many of my father’s paid servants have more food than they want, and here am I dying of hunger!” Yes, there was an acknowledgment that he had made a miscalculated move. He thought he would be better off on his own without his father but now realises that even his father’s servants have it better than him. But this was short of a contrition for his past faults. Hidden within this selfish and self-centred logic, is also the uneasy acknowledgment of his father’s generosity - that the servants under his father enjoy a lifestyle better than they could ever deserve and would ever need. But such acknowledgment was the first step to his repentance.

We are then presented with another amazing fact that the father in this story, whom every reader now understands, refers to God the Heavenly Father. “Nowhere else,” remarked the theologian Hans von Balthasar, “does Jesus portray the Father in heaven more vitally, more plainly.” This father, or God whom he represents, has never given up hope on his wayward and ungrateful son. The son may have turned his back on his father, he may have wished his father dead, he may have squandered his inheritance which the father had given him, but now returns to a father who has never given up or written off or turned his back on his son.

In Rublev’s icon of the Hospitality of Abraham, or more commonly known as the Icon of the Most Holy Trinity, the symbol in the backdrop which identifies one of the three nondescript angelic figures as a representation of God the Father (most often identified as the figure on the left), is a house with a tower and a large window. From this tower, it is said, the father of the Lost Son would keep vigil, look out throughout the day and survey the horizon so as to catch the first sign of his son’s return. As much as we are reminded to keep vigilant and stay awake for the Lord’s return, know this to be true: God never lets His guard down, God is always watching for our return.

And so, we have this poignantly beautiful description of how the reconciliation of the father and the son takes place: “While he was still a long way off, his father saw him and was moved with pity. He ran to the boy, clasped him in his arms and kissed him tenderly.” The father meets the son more than halfway, embraces him in love, even before the son was given an opportunity to utter his first words of apology. God’s “I love you” always precedes our pitiful and often half-hearted “I’m sorry.” “When you are still far away, he sees you and runs to you,” wrote St. Ambrose, “He sees in your heart. He runs, perhaps someone may hinder, and He embraces you. His foreknowledge is in the running, His mercy in the embrace and the disposition of fatherly love.” God offers life and love to every wayward soul; He runs to embrace the returning sinner.

How is the reconciliation sealed? One would imagine that the son is expected to pay back what he owed his father (with interests thrown in) or, work to pay off the debt and to prove his trustworthiness after this massive loss in confidence. But the father’s love goes beyond what we could ever imagine. Instead of demanding for recompense, the father lavishly pours out more gifts on this son: “Bring out the best robe and put it on him; put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. Bring the calf we have been fattening, and kill it; we are going to have a feast, a celebration…”

And so, we have this poignantly beautiful description of how the reconciliation of the father and the son takes place: “While he was still a long way off, his father saw him and was moved with pity. He ran to the boy, clasped him in his arms and kissed him tenderly.” The father meets the son more than halfway, embraces him in love, even before the son was given an opportunity to utter his first words of apology. God’s “I love you” always precedes our pitiful and often half-hearted “I’m sorry.” “When you are still far away, he sees you and runs to you,” wrote St. Ambrose, “He sees in your heart. He runs, perhaps someone may hinder, and He embraces you. His foreknowledge is in the running, His mercy in the embrace and the disposition of fatherly love.” God offers life and love to every wayward soul; He runs to embrace the returning sinner.

How is the reconciliation sealed? One would imagine that the son is expected to pay back what he owed his father (with interests thrown in) or, work to pay off the debt and to prove his trustworthiness after this massive loss in confidence. But the father’s love goes beyond what we could ever imagine. Instead of demanding for recompense, the father lavishly pours out more gifts on this son: “Bring out the best robe and put it on him; put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. Bring the calf we have been fattening, and kill it; we are going to have a feast, a celebration…”

What do we see in these 5 gifts? All these point to the Son. Who is this son? Definitely not the lost son who had sinned against the father and now returns in shame. Neither do these belong to the older son, who at the end of the parable has yet to “come to his senses,” which makes his younger brother better than him. You can’t earn these gifts. No, these gifts are the birthright of neither of these two sons but they belong to the One who is telling this story. It is Jesus Christ, whose garments are stripped from His body, who now confer the garment of righteousness upon those who have been baptised in His name and who now share in His death and resurrection. It is Jesus Christ, the Bridegroom, who now places the ring upon the finger of His Bride, the Church, whom He has washed clean with His blood shed on the cross. It is Jesus Christ, the Way, the Truth and the Life, who now invites us to walk in His shoes, His sandals. And it is Jesus Christ, the unblemished Paschal Lamb, the fatted calf, who offers His life as a sacrifice on the cross and now feeds us with His Body and Blood in the endless feast of the Eucharist.

Yes, we all need to come to our senses. We all need to recognise that life can never be good apart from God. We all need to acknowledge that God owes us nothing, whether by virtue of our birthright, as in the case of the younger son, or by earning it like the older son. God’s riches and our inheritance of Eternal Life can never be earned nor is it something we are entitled to. Because He loves us, God has lavishly poured out upon us His most precious treasure of all. As St John so beautifully puts it: “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” (John 3:16)