Solemnity of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ Year B

Many a young child’s dream and ambition of becoming a doctor had been dashed by one simple fear - they were haemophobic. Not “homophobic” but “haemophobic”, the fear of blood, wounds and injuries. So, if you happen to have this sad condition, today’s feast and its readings, if you had really listened and paid attention to every word, may make your stomach churn. What unites all three readings is the mention of blood and bodies? Today’s feast is definitely a bloody affair!

Why is blood and a corpse involved in today’s feast? It would be stating the obvious that we are speaking of the blood and body of Jesus Christ since this is the proper name of this feast. But to understand why our Lord would sacrifice both His Body and Blood, we would need to understand two concepts in the Bible, that of sacrifice and the covenant.

The idea of sacrifice arises from the first and the highest duty of man, which is to hand himself over, to surrender, to submit himself to God. This sacrifice involves two parts - first, an interior and invisible offering of ourselves to God; and second, this offering must be outwardly and sensibly signified. In other words, one cannot sacrifice by merely intending it and making a mental offering to God. This must be matched by an external sign which signifies and makes visible that internal sign. This is fundamentally the basis of our sacramental theology - outward sign of inward grace.

What the Pharisees were guilty of and which our Lord condemned was that they had confined their sacrifices to outward show but lack the interior disposition necessary to make a true offering of oneself. Virtue signalling is a modern term coined for this. Today, the tendency is reversed. Many modern Christians argue that good intentions are enough and we should disregard external rituals and practices which are considered showy and frivolous. This would explain why so many Christians have abandoned the Holy Mass and even removed the altars from their sanctuaries.

But, for the Jews, the shedding of blood and the immolation (or killing) of the animal was necessary for the atonement of one’s sins. This was not just something which man cooked up in his sadistic blood thirsty mind but was in fact commanded by God. According to Hebrews (9:22), “Without the shedding of blood there is no remission.” By the very act of offering and giving these animals over to death, men acknowledged that they themselves were deserving of death because of their sins; and in this action, they expressly admitted, that did God will to judge them as their sins deserved, He could in justice inflict death on them. These poor animals would literally be the “scape goats” that take away the sins of the world. But the sad truth, as Hebrews tells us, is that these animal sacrifices could not remove the stain of our sins, nor could they reconcile us with God. A far greater and more perfect sacrifice was necessary.

Before considering that far greater sacrifice, it is necessary to look at another purpose of such blood sacrifices. Blood and sacrifice were also needed in the sealing of covenants. Ancient peoples did not just resort to lawyers and their penmanship to enact pacts with each other. Pacts and covenants were sacred affairs and to make them lasting and their breaking almost impossible, the gods were invoked to not only stand as witnesses to these agreements between mortals but to also be a party to them.

So, from the very beginning, the patriarchs entered into covenants with God by making animal sacrifices - Noah, Abraham and Moses just to name a few. The Mosaic covenant which we heard in the first reading required that the blood of the sacrificed animals be sprinkled on the altar, the tabernacle as well as the people. Just imagine the climatic scene in Stephen King’s Firestarter, where the protagonist Carrie is drenched in pig’s blood. In fact, everything that is to be used in the ritual sacrifice had to be cleansed with blood, not water. Can you picture a more bloody scene than this and happening in the sacred Temple of all places? With the use of blood in the sealing of the covenant, God, in essence, was declaring He would give His life if His promises were broken. There could be no greater encouragement to believers, since God is eternal and can no more break an oath than He can die.

All of these things were only “copies,” or “shadows,” of the better and more perfect covenant to come. The lives of animals could never remove sin; the life of an animal is not a sufficient substitute for a human life. The blood of bulls and goats was a temporary appeasement until the final, ultimate blood covenant was made by Jesus Christ Himself – the God Man. In the second reading, the author of Hebrews tells us that “the blood of goats and bulls and the ashes of a heifer are sprinkled on those who have incurred defilement and they restore the holiness of their outward lives; how much more effectively the blood of Christ, who offered himself as the perfect sacrifice to God through the eternal Spirit, can purify our inner self from dead actions so that we do our service to the living God.” Furthermore, Hebrews adds this claim: “His death took place to cancel the sins that infringed the earlier covenant. The shadows became realities in Christ, who fulfilled all of the Old Testament blood covenants with His own blood.”

We often forget that the Eucharist is the sign which signifies the new covenant of Jesus, and because it is a covenant, it also makes demands of us. Whenever we partake of this sacrifice and covenantal meal, we are declaring what Moses did in the first reading, but in a far more intense and firmer way: “We will observe all the commands that the Lord has decreed.” This becomes a real challenge to your average cafeteria Catholic, and there are many who fit this label. What is a cafeteria Catholic or using a metaphor closer to home - an economy mixed rice Catholic? A cafeteria Catholic is typically defined as one who picks and chooses what Catholic teaching he wants to believe. But the truth of the matter and a bitter pill to swallow, is that Catholics are not free to choose which teachings to obey. The faithful must give “a religious submission of the intellect and will” to the teachings of Christ and His Church. First and foremost, would be the faithful celebration of the sacraments of the Church according to their proper rubrics (rules) and not just adapt and make alterations which suit the celebrant’s preferences. It is hard to justify when claiming that one values Christ but chooses to ignore or reject what His Church teaches. Eschewing cafeteria Catholicism might satisfy our appetite temporarily, but only the full banquet prepared by the Lord can fill our souls.

Tuesday, May 28, 2024

Wednesday, May 22, 2024

Central Mystery of Faith

Solemnity of the Most Holy Trinity Year B

Today we celebrate Trinity Sunday. On other days in our liturgical calendar, we primarily celebrate the mystery of the life of Christ, His Incarnation, His ministry, His passion, death and resurrection and the impact this has on the Church and her members, in particular Mary and the saints. But today, we celebrate the mystery of who God is — the Most Holy Trinity. It is one of only two dogmas that actually have a feast day in the liturgical calendar. The term “mystery” is appropriate for the celebration.

I hate to do it but whenever I’m asked a question of clarification about the Most Holy Trinity, transubstantiation or the Incarnation, I would start with my standard curt reply: “it’s a mystery.” Though, this may appear to be a brilliant deflection and avoidance of answering the question directly, I can presume that it must sound awfully frustrating and condescending to the enquirer. But it is not my intention to deflect or avoid and I’m hardly trying to be condescending. I would proceed to explain what a mystery means in its theological context. It’s hardly Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew or Agatha Christie stuff which I am talking about. A mystery of faith is of a different category entirely.

When the Church refers to a teaching, a dogma, as mystery, she is not referring to something which is hidden from our knowledge - it is not some esoteric secret. In fact, mysteries of faith are part of divine revelation - their secrets have been revealed to us. But when the Church describes something as mystery, she is making the point that this truth cannot be known to us independently of such revelation from God. Our natural faculties including our intellect would not be able to arrive at this conclusion without God Himself having revealed or shown it to us.

And so it is with the dogma of the Most Holy Trinity. God is so far above us that we can never fully understand Him. We mortals would be incapable of knowing that God exists as One but in three distinct persons if this has not been revealed to us through Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition. In fact, the dogma of the Most Holy Trinity is not just one example of a mystery among many. The Catechism of the Catholic Church declares: “The mystery of the Most Holy Trinity is the central mystery of Christian faith and life. It is the mystery of God in Himself. It is therefore the source of all the other mysteries of faith, the light that enlightens them” (CCC 234). It would be ironic if we wish to delve into the meaning of other mysteries of faith and yet deliberately choose to ignore the central mystery of our faith just because it is the most inexplicable and most likely to give us a major headache.

There could be two major mistakes we are prone to make when considering the Most Holy Trinity as a mystery, even though it is uniquely described as the “central mystery of Christian faith and life.”

The first is to treat the dogma as a fascinating but abstract concept, a cosmic Rubik’s Cube that challenges us to fit all the pieces into their place through elaborate, brain-twisting moves. What might begin as a sincere desire to understand better the mystery of One God in three persons can be a dry academic exercise. If we’re not careful, the Trinity can become a sort of theological artifact that is interesting to examine on occasion, but which doesn’t affect how we think, speak, and live.

The second mistake is to simply avoid thoughtful consideration of the nature and meaning of the Trinity. The end result of this flawed perspective is similar to the first, minus all the study: to throw up one’s hands in frustrated impatience, “Well, it doesn’t make any sense. I don’t see what it has to do with me and my life!” While many Christians might not consciously come to that conclusion, the way they think and live suggests that is, unfortunately, their attitude.

Far from being a distant concept remotely removed from our everyday lives, it is fundamental to our identity as Christians. In a sermon given in the early 1970s, Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) wrote of how “the Church makes a man a Christian by pronouncing the name of the triune God.” This is what our Lord wishes to communicate in today’s passage as He commissions His disciples with this mission: “Go, therefore, make disciples of all the nations; baptise them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teach them to observe all the commands I gave you.” The baptism that takes place is to be done in the name of the Most Holy Trinity.

Although the word “mystery” implies a certain distance, it involves an intimate encounter. A relationship would remain shallow if the parties are not willing to open themselves to the other. As some people would argue, there should be no secrets between lovers. The reason why God would unlock and reveal a mystery to us is because He loves us and wishes to engage us and wants us to enter into a relationship with Him. Through this relationship we come to know Him and by knowing Him more and more, we get to deepen our relationship with Him. This knowledge, admittedly, is not exhaustive but engaging. It draws us closer to the One who can never be fully known. It is a relationship of love. Just like the more you get to know someone you love, the more the person is revealed to be a mystery.

Now that we know His motivation is love, but why would God bother to reveal Himself to us? That we might have Eternal Life. And what is eternal life? It is actually sharing in the supernatural life of the Blessed Trinity. How can we share in a life which we have no knowledge of? Impossible. That is why, the more we come to know God, the more we wish to enter into a deeper communion with Him.

Far from being abstract or of little earthly value, the Most Holy Trinity is the source of reality and the reason our earthly lives have meaning and purpose. Because God is, we have a reason to be. Because God is love, we are able to truly love. Because God is unity, we are able to be united to Him. Because God is three Persons, we are able to have communion with Him. This is the reason why this dogma is the central mystery of faith.

St. Gregory of Nazianzus once wrote, “Above all guard for me this great deposit of faith for which I live and fight, which I want to take with me as a companion, and which makes me bear all evils and despise all pleasures: I mean the profession of faith in the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.” (CCC 256). We may not completely grasp the height and the depth of this great mystery but what St Paul wrote to the Corinthians helps us to embrace this mystery and relationship: “For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known. And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love” (1 Cor 13:12-13). May we guard our belief in the Triune God with our lives. And may we better know the Most Holy Trinity, so that “we may love Him, serve Him and be with Him in paradise forever”.

Today we celebrate Trinity Sunday. On other days in our liturgical calendar, we primarily celebrate the mystery of the life of Christ, His Incarnation, His ministry, His passion, death and resurrection and the impact this has on the Church and her members, in particular Mary and the saints. But today, we celebrate the mystery of who God is — the Most Holy Trinity. It is one of only two dogmas that actually have a feast day in the liturgical calendar. The term “mystery” is appropriate for the celebration.

I hate to do it but whenever I’m asked a question of clarification about the Most Holy Trinity, transubstantiation or the Incarnation, I would start with my standard curt reply: “it’s a mystery.” Though, this may appear to be a brilliant deflection and avoidance of answering the question directly, I can presume that it must sound awfully frustrating and condescending to the enquirer. But it is not my intention to deflect or avoid and I’m hardly trying to be condescending. I would proceed to explain what a mystery means in its theological context. It’s hardly Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew or Agatha Christie stuff which I am talking about. A mystery of faith is of a different category entirely.

When the Church refers to a teaching, a dogma, as mystery, she is not referring to something which is hidden from our knowledge - it is not some esoteric secret. In fact, mysteries of faith are part of divine revelation - their secrets have been revealed to us. But when the Church describes something as mystery, she is making the point that this truth cannot be known to us independently of such revelation from God. Our natural faculties including our intellect would not be able to arrive at this conclusion without God Himself having revealed or shown it to us.

And so it is with the dogma of the Most Holy Trinity. God is so far above us that we can never fully understand Him. We mortals would be incapable of knowing that God exists as One but in three distinct persons if this has not been revealed to us through Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition. In fact, the dogma of the Most Holy Trinity is not just one example of a mystery among many. The Catechism of the Catholic Church declares: “The mystery of the Most Holy Trinity is the central mystery of Christian faith and life. It is the mystery of God in Himself. It is therefore the source of all the other mysteries of faith, the light that enlightens them” (CCC 234). It would be ironic if we wish to delve into the meaning of other mysteries of faith and yet deliberately choose to ignore the central mystery of our faith just because it is the most inexplicable and most likely to give us a major headache.

There could be two major mistakes we are prone to make when considering the Most Holy Trinity as a mystery, even though it is uniquely described as the “central mystery of Christian faith and life.”

The first is to treat the dogma as a fascinating but abstract concept, a cosmic Rubik’s Cube that challenges us to fit all the pieces into their place through elaborate, brain-twisting moves. What might begin as a sincere desire to understand better the mystery of One God in three persons can be a dry academic exercise. If we’re not careful, the Trinity can become a sort of theological artifact that is interesting to examine on occasion, but which doesn’t affect how we think, speak, and live.

The second mistake is to simply avoid thoughtful consideration of the nature and meaning of the Trinity. The end result of this flawed perspective is similar to the first, minus all the study: to throw up one’s hands in frustrated impatience, “Well, it doesn’t make any sense. I don’t see what it has to do with me and my life!” While many Christians might not consciously come to that conclusion, the way they think and live suggests that is, unfortunately, their attitude.

Far from being a distant concept remotely removed from our everyday lives, it is fundamental to our identity as Christians. In a sermon given in the early 1970s, Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) wrote of how “the Church makes a man a Christian by pronouncing the name of the triune God.” This is what our Lord wishes to communicate in today’s passage as He commissions His disciples with this mission: “Go, therefore, make disciples of all the nations; baptise them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teach them to observe all the commands I gave you.” The baptism that takes place is to be done in the name of the Most Holy Trinity.

Although the word “mystery” implies a certain distance, it involves an intimate encounter. A relationship would remain shallow if the parties are not willing to open themselves to the other. As some people would argue, there should be no secrets between lovers. The reason why God would unlock and reveal a mystery to us is because He loves us and wishes to engage us and wants us to enter into a relationship with Him. Through this relationship we come to know Him and by knowing Him more and more, we get to deepen our relationship with Him. This knowledge, admittedly, is not exhaustive but engaging. It draws us closer to the One who can never be fully known. It is a relationship of love. Just like the more you get to know someone you love, the more the person is revealed to be a mystery.

Now that we know His motivation is love, but why would God bother to reveal Himself to us? That we might have Eternal Life. And what is eternal life? It is actually sharing in the supernatural life of the Blessed Trinity. How can we share in a life which we have no knowledge of? Impossible. That is why, the more we come to know God, the more we wish to enter into a deeper communion with Him.

Far from being abstract or of little earthly value, the Most Holy Trinity is the source of reality and the reason our earthly lives have meaning and purpose. Because God is, we have a reason to be. Because God is love, we are able to truly love. Because God is unity, we are able to be united to Him. Because God is three Persons, we are able to have communion with Him. This is the reason why this dogma is the central mystery of faith.

St. Gregory of Nazianzus once wrote, “Above all guard for me this great deposit of faith for which I live and fight, which I want to take with me as a companion, and which makes me bear all evils and despise all pleasures: I mean the profession of faith in the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.” (CCC 256). We may not completely grasp the height and the depth of this great mystery but what St Paul wrote to the Corinthians helps us to embrace this mystery and relationship: “For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known. And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love” (1 Cor 13:12-13). May we guard our belief in the Triune God with our lives. And may we better know the Most Holy Trinity, so that “we may love Him, serve Him and be with Him in paradise forever”.

Monday, May 13, 2024

Life in the Spirit

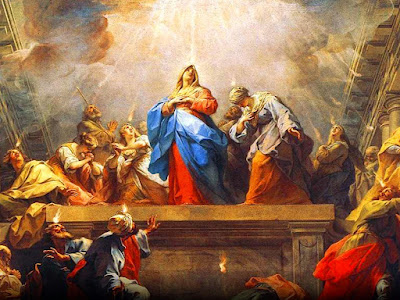

Pentecost Sunday Year B

The Catholic Charismatic Renewal has undoubtedly been a great gift to the Catholic Church in recent times as it has brought about a revival and renewed enthusiasm of faith among Catholics, often going against the mainstream trend of declining church attendees and vocations, cooling of devotional fervour among the faithful and over rationalisation of the clergy. Many a priestly or religious vocation and person deeply committed to lay apostolate would have attributed the seeds of their call to the renewal and the work of the Holy Spirit.

However, there is a danger of confining the work of the Holy Spirit to mere external signs in the vein of what took place at Pentecost which is recounted in the first reading - visible and tangible manifestation of the power of the Holy Spirit and the display of the charismata - the charismatic gifts of speaking in tongues and miracles. A deeper look at the work of the Holy Spirit will necessitate looking at the long-term fruits of the Spirit working in the life of a Christian. St Paul gives us this invaluable tool of discernment in the second reading. As we were reminded in a recent course on exorcism and spiritual warfare, the devil and his minions can imitate the charisms in that they can suspend and bend the laws of nature and our hunger for the spectacular, but only God and His Holy Spirit can plant the hidden fruits of spiritual grace in our lives and bring about our sanctification.

St Paul gives a full list of works of the Spirit and their opposites, the works of the flesh, that is, the works of natural, unreformed and selfish behaviour. Christ has sent His Spirit so that our behaviour may be completely changed, and so that we may live with His life. The works of the flesh are not merely the gross, ‘fleshly’ distortions of greed, avarice and sexual licence, but include also such failings as envy and quarrels. Paul’s list is a useful little checklist to apply to our own way of life. The desires of self-indulgence are always in opposition to the Spirit, and the desires of the Spirit are in opposition to self-indulgence: they are opposites, one against the other; that is how you are prevented from doing the things that you want to.

What is self-indulgence and why is it the greatest threat to a life in the Spirit? Self-indulgence, simply put, is desire for pleasure. If we look carefully at people today and modern society in general, we see immediately that they are dominated by the passion of love of pleasure or self-indulgence. Our age is pleasure-seeking to the highest degree. Even in spirituality, so many seek to experience an emotional high in prayer rather than do the hard work of building virtue. Human beings have a constant tendency towards this terrible passion, which destroys their whole life and deprives them of the possibility of communion with God. The passion of self-indulgence wrecks the work of salvation.

According to the Fathers of the Church, self-indulgence is one of the main causes of every abnormality in man’s spiritual and bodily organism. It is the source of all the vices and all the passions that assault both soul and body. St Theodore, Bishop of Edessa, teaches that there are three general passions which give rise to all the others: love of pleasure, love of money and love of praise. Other evil spirits originate from these three, and subsequently “from these arise a great swarm of passions and all manner of evil.” St John of Damascus makes the same point. “The roots or primary causes of all these passions are love of sensual pleasure, love of praise and love of material wealth. Every evil has its origin in these.” Since love of money and praise include the intense sensual pleasure derived from wealth and glory, we can say that self-indulgence gives birth to all the other passions.

The antidote and cure to this predilection to sin is living a vibrant life in the Spirit. St Paul assured us that “If you are guided by the Spirit you will be in no danger of yielding to self-indulgence, since self-indulgence is the opposite of the Spirit, the Spirit is totally against such a thing.” Paul does not only list down the bad fruits which come from the spirit of self-indulgence but also provides us with a list of nine fruits of the Holy Spirit: “love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, trustfulness, gentleness and self-control”. Notice how self-control is listed last instead of first even though we may assume that self-control is the clearest antidote to self-indulgence. And yet, love is listed first. The reason is that love always seeks the well-being of the other rather than oneself, and if there is no love even in the ascetic practices of our faith, we are merely empty gongs and everything we do, even if it has the appearance of a virtue, is self-serving.

St Paul understood that the early Church whom he was writing to is made up of baptised Christians, who have died and been reborn with Christ and have received the Holy Spirit who descended on the day of Pentecost and is still a battleground of spiritual warfare between the spirit of indulgence and that of the Holy Spirit. If that were not the case, he wouldn’t have warned his audience about this nor would our Lord give us the power of the Spirit to forgive sins if every member of the Church was a perfect living saint devoid of sin. It is precisely, because we continue to struggle with self-indulgence that we have to constantly allow the Spirit to fortify us and strengthen our resolve to be holy and faithful to the Lord.

When our Lord appeared to the disciples in the Upper Room after His resurrection and greeted them with the gift of peace, it did not mean that their lives would now be secured and immune from trouble, conflict or even sin. Peace is not the absence of something but rather the presence of someone, our Lord Jesus Christ, who continues to work through His Church by the power of the Holy Spirit, forgiving sins, healing wounds, regenerating persons, and redeeming them from the world and the life of sin. The Church, as the third-century theologian St Hippolytus affirmed, is “the place where the Spirit flourishes”. The Church is the dwelling place of the Holy Spirit, the Spirit animating and bringing to life and holiness its members through the Word and sacraments, the ministry of the ordained (our bishops, priests and deacons), the various gifts and charisms of the faithful of every rank, the varieties of religious orders and ecclesial movements that express the Spirit’s power and anointing.

Today, we remember how the Risen Lord had breathed His Spirit on the apostles and on all of us: “Receive the Holy Spirit!” The Spirit comes to each one of us as a gift but also as a challenge to the ongoing conversion of our heart and mind. As the source and giver of all holiness, we implore the Spirit to keep us in grace and remove those artificial obstacles, habits and ways of thinking that prevent us from living fully in and for Christ. As St Paul writes in the Letter to the Romans, our baptism in Christ calls us to live no longer by the flesh, by the material things or selfish desires of this world, but to live according to the Spirit (Rom 8:5).

The Catholic Charismatic Renewal has undoubtedly been a great gift to the Catholic Church in recent times as it has brought about a revival and renewed enthusiasm of faith among Catholics, often going against the mainstream trend of declining church attendees and vocations, cooling of devotional fervour among the faithful and over rationalisation of the clergy. Many a priestly or religious vocation and person deeply committed to lay apostolate would have attributed the seeds of their call to the renewal and the work of the Holy Spirit.

However, there is a danger of confining the work of the Holy Spirit to mere external signs in the vein of what took place at Pentecost which is recounted in the first reading - visible and tangible manifestation of the power of the Holy Spirit and the display of the charismata - the charismatic gifts of speaking in tongues and miracles. A deeper look at the work of the Holy Spirit will necessitate looking at the long-term fruits of the Spirit working in the life of a Christian. St Paul gives us this invaluable tool of discernment in the second reading. As we were reminded in a recent course on exorcism and spiritual warfare, the devil and his minions can imitate the charisms in that they can suspend and bend the laws of nature and our hunger for the spectacular, but only God and His Holy Spirit can plant the hidden fruits of spiritual grace in our lives and bring about our sanctification.

St Paul gives a full list of works of the Spirit and their opposites, the works of the flesh, that is, the works of natural, unreformed and selfish behaviour. Christ has sent His Spirit so that our behaviour may be completely changed, and so that we may live with His life. The works of the flesh are not merely the gross, ‘fleshly’ distortions of greed, avarice and sexual licence, but include also such failings as envy and quarrels. Paul’s list is a useful little checklist to apply to our own way of life. The desires of self-indulgence are always in opposition to the Spirit, and the desires of the Spirit are in opposition to self-indulgence: they are opposites, one against the other; that is how you are prevented from doing the things that you want to.

What is self-indulgence and why is it the greatest threat to a life in the Spirit? Self-indulgence, simply put, is desire for pleasure. If we look carefully at people today and modern society in general, we see immediately that they are dominated by the passion of love of pleasure or self-indulgence. Our age is pleasure-seeking to the highest degree. Even in spirituality, so many seek to experience an emotional high in prayer rather than do the hard work of building virtue. Human beings have a constant tendency towards this terrible passion, which destroys their whole life and deprives them of the possibility of communion with God. The passion of self-indulgence wrecks the work of salvation.

According to the Fathers of the Church, self-indulgence is one of the main causes of every abnormality in man’s spiritual and bodily organism. It is the source of all the vices and all the passions that assault both soul and body. St Theodore, Bishop of Edessa, teaches that there are three general passions which give rise to all the others: love of pleasure, love of money and love of praise. Other evil spirits originate from these three, and subsequently “from these arise a great swarm of passions and all manner of evil.” St John of Damascus makes the same point. “The roots or primary causes of all these passions are love of sensual pleasure, love of praise and love of material wealth. Every evil has its origin in these.” Since love of money and praise include the intense sensual pleasure derived from wealth and glory, we can say that self-indulgence gives birth to all the other passions.

The antidote and cure to this predilection to sin is living a vibrant life in the Spirit. St Paul assured us that “If you are guided by the Spirit you will be in no danger of yielding to self-indulgence, since self-indulgence is the opposite of the Spirit, the Spirit is totally against such a thing.” Paul does not only list down the bad fruits which come from the spirit of self-indulgence but also provides us with a list of nine fruits of the Holy Spirit: “love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, trustfulness, gentleness and self-control”. Notice how self-control is listed last instead of first even though we may assume that self-control is the clearest antidote to self-indulgence. And yet, love is listed first. The reason is that love always seeks the well-being of the other rather than oneself, and if there is no love even in the ascetic practices of our faith, we are merely empty gongs and everything we do, even if it has the appearance of a virtue, is self-serving.

St Paul understood that the early Church whom he was writing to is made up of baptised Christians, who have died and been reborn with Christ and have received the Holy Spirit who descended on the day of Pentecost and is still a battleground of spiritual warfare between the spirit of indulgence and that of the Holy Spirit. If that were not the case, he wouldn’t have warned his audience about this nor would our Lord give us the power of the Spirit to forgive sins if every member of the Church was a perfect living saint devoid of sin. It is precisely, because we continue to struggle with self-indulgence that we have to constantly allow the Spirit to fortify us and strengthen our resolve to be holy and faithful to the Lord.

When our Lord appeared to the disciples in the Upper Room after His resurrection and greeted them with the gift of peace, it did not mean that their lives would now be secured and immune from trouble, conflict or even sin. Peace is not the absence of something but rather the presence of someone, our Lord Jesus Christ, who continues to work through His Church by the power of the Holy Spirit, forgiving sins, healing wounds, regenerating persons, and redeeming them from the world and the life of sin. The Church, as the third-century theologian St Hippolytus affirmed, is “the place where the Spirit flourishes”. The Church is the dwelling place of the Holy Spirit, the Spirit animating and bringing to life and holiness its members through the Word and sacraments, the ministry of the ordained (our bishops, priests and deacons), the various gifts and charisms of the faithful of every rank, the varieties of religious orders and ecclesial movements that express the Spirit’s power and anointing.

Today, we remember how the Risen Lord had breathed His Spirit on the apostles and on all of us: “Receive the Holy Spirit!” The Spirit comes to each one of us as a gift but also as a challenge to the ongoing conversion of our heart and mind. As the source and giver of all holiness, we implore the Spirit to keep us in grace and remove those artificial obstacles, habits and ways of thinking that prevent us from living fully in and for Christ. As St Paul writes in the Letter to the Romans, our baptism in Christ calls us to live no longer by the flesh, by the material things or selfish desires of this world, but to live according to the Spirit (Rom 8:5).

The Birth of the New Israel

Pentecost Vigil Mass

Many of you may be disappointed with the readings for this Vigil Mass. You were expecting to hear the story from the Acts of the Apostles of how the Holy Spirit descended upon them in the form of tongues of fire and how they burst out in glossolalia, speech which miraculously could be understood by pilgrims from various nations in their own mother tongue. But none of that in today’s readings. In fact, the first reading gives us an account of the theophany at Mount Sinai, which surprisingly sounds similar to our familiar story of the Pentecost.

But these two events are not entirely unconnected. To understand their close connexion, one needs to understand that Pentecost was first and foremost a Jewish Feast before it entered into the Christian calendar. Initially, Pentecost was the feast of seven weeks. Pentecost, or Shavuot in Hebrew, means fifty and is basically the sum total of seven weeks of seven days with an additional day added to the multiple of seven as how one would calculate a jubilee year. The Israelites left Egypt on the fifteenth day of the first month, the morning after the sacrifice of the Passover Lamb. They arrived at the foot of Mt. Sinai on the first day of the third month, which would have been approximately forty days. Moses then went up Mt Sinai and stayed there for several days and then brought back down the two tablets written on stone by the finger of God. This total timeline closely approximated the fifty days after Passover that the Feast of Shavuot was supposed to be held on.

Shavuot was, like the other two pilgrimage festivals of Pesach (Passover) and Sukkoth (Tabernacles or Booths), a harvest feast (cf. Ex 23:16), when the new grain was offered to God (cf. Nm 28:26; Dt 16:9). Later on, the feast acquired a new meaning: it became the feast of the Covenant God had made with His people on Sinai, when He gave Israel His law. The event which is narrated in today’s first reading. We still have one last piece of the puzzle. How is this feast significant for us Christians and why would God choose to pour out the Holy Spirit on the apostles on this day? The same day that the Jews were celebrating God’s giving of His Torah on tablets of stone, the Holy Spirit came and wrote His Torah on people’s hearts!

St Luke describes the Pentecost event as a theophany, a manifestation of God similar to the one on Mt Sinai: a roaring sound, a mighty wind, tongues of fire. But there is more. Both events occurred on a mountain (Mt. Sinai and Mt. Zion). Both events happened to a newly redeemed people. The Exodus marked the birth of the Israelite nation while the Pentecost event marked the birth of the Church.

The message is clear: Pentecost is the new Sinai; the Holy Spirit is the New Covenant; and once again there is the gift of the new Law to the Church, the New Israel. But the parallels are not just meant to be equivalent. The Christian Pentecost is meant to be the fulfilment of what was merely foreshadowed in the Old Testament - a definite upgrade. At Sinai the people were kept away from the fire on the mountain because they had not purified themselves. But at Pentecost, the fire comes into their midst through the Apostles. At Sinai, God gave the Law written by His finger on tablets of stone. At Pentecost, He gave the Law written on Tablets of the Heart. The Torah attempted to change people from the outside. The Holy Spirit changes from within.

The promise made to the prophets is thus fulfilled. We read in the prophet Jeremiah: “This is the covenant which I will make with the house of Israel after those days, says the Lord: I will put my law within them, and I will write it upon their hearts” (Jer 31:33). And in the prophet Ezekiel: “A new heart I will give you, and a new spirit I will put within you; and I will take out of your flesh the heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh. And I will put my Spirit within you, and cause you to walk in my statutes and be careful to observe my ordinances” (Ez 36:26-27).

The law of Moses pointed out obligations but could not change the human heart. A new heart was needed, and that is precisely what God offers us by virtue of the redemption accomplished by Jesus. The Father removes our heart of stone and gives us a heart of flesh like Christ’s, enlivened by the Holy Spirit who enables us to act out of love (cf. Rom 5:5). On the basis of this gift, a new Covenant is established between God and humanity. St Thomas Aquinas says with keen insight that the Holy Spirit Himself is the New Covenant, producing love in us, the fullness of the law.

This is the last and perhaps the most important of the parallels. At Sinai, after the people receive the law of the Lord, they swear a covenant with God. A covenant is how families are created. That’s the purpose of a covenant. When God swears His covenant with us, it’s to make us His family. The whole story of the Bible is a story of covenants as God is reuniting us with His family, which Adam got kicked out of. So God makes covenants with Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses and David. The Old Covenant sealed at Sinai is now replaced by the New at Pentecost. These Old Testament covenants are finally fulfilled in the New Covenant of Jesus Christ where finally the family of God isn’t only dictated by natural bloodlines, but through the blood of Jesus Christ.

The covenant of Sinai was broken by the people’s apostasy and rebellion when they demanded that Aaron make a golden calf as an object of worship, Moses ordered the Levites to slaughter the idolaters. It was said that 3,000 were killed. If you recall from the account of Pentecost in the Acts of the Apostles, how many were baptised and added to the Church on that day? 3,000. In other words, the 3,000 lost through the broken covenant at the foot of Sinai in the old Israel is restored to the New Israel – the Church - because of the New Covenant of Jesus Christ. This is the birth of the new people of God. What was dead has been brought back to life through the power of the Holy Spirit – through the sacraments.

So, there you have it. The backstory of Pentecost in the book of Acts is the scene at Sinai way back at the birth of Israel as the people of God. We are the new people of God. We are the New Israel, the restored and transformed kingdom of God in the New Covenant of Jesus Christ! Thanks be to God for the Holy Spirit! He brings us life. He manifests God in our presence. He continues the power of the resurrected and ascended Christ in our lives. It is the Spirit that gives life. The Holy Spirit brings Christ to us through the sacraments. He guides in the life of prayer. He draws us closer to our Lord so that we can fulfill our destiny as children of God. Don’t ever stop asking for the Holy Spirit.

Many of you may be disappointed with the readings for this Vigil Mass. You were expecting to hear the story from the Acts of the Apostles of how the Holy Spirit descended upon them in the form of tongues of fire and how they burst out in glossolalia, speech which miraculously could be understood by pilgrims from various nations in their own mother tongue. But none of that in today’s readings. In fact, the first reading gives us an account of the theophany at Mount Sinai, which surprisingly sounds similar to our familiar story of the Pentecost.

But these two events are not entirely unconnected. To understand their close connexion, one needs to understand that Pentecost was first and foremost a Jewish Feast before it entered into the Christian calendar. Initially, Pentecost was the feast of seven weeks. Pentecost, or Shavuot in Hebrew, means fifty and is basically the sum total of seven weeks of seven days with an additional day added to the multiple of seven as how one would calculate a jubilee year. The Israelites left Egypt on the fifteenth day of the first month, the morning after the sacrifice of the Passover Lamb. They arrived at the foot of Mt. Sinai on the first day of the third month, which would have been approximately forty days. Moses then went up Mt Sinai and stayed there for several days and then brought back down the two tablets written on stone by the finger of God. This total timeline closely approximated the fifty days after Passover that the Feast of Shavuot was supposed to be held on.

Shavuot was, like the other two pilgrimage festivals of Pesach (Passover) and Sukkoth (Tabernacles or Booths), a harvest feast (cf. Ex 23:16), when the new grain was offered to God (cf. Nm 28:26; Dt 16:9). Later on, the feast acquired a new meaning: it became the feast of the Covenant God had made with His people on Sinai, when He gave Israel His law. The event which is narrated in today’s first reading. We still have one last piece of the puzzle. How is this feast significant for us Christians and why would God choose to pour out the Holy Spirit on the apostles on this day? The same day that the Jews were celebrating God’s giving of His Torah on tablets of stone, the Holy Spirit came and wrote His Torah on people’s hearts!

St Luke describes the Pentecost event as a theophany, a manifestation of God similar to the one on Mt Sinai: a roaring sound, a mighty wind, tongues of fire. But there is more. Both events occurred on a mountain (Mt. Sinai and Mt. Zion). Both events happened to a newly redeemed people. The Exodus marked the birth of the Israelite nation while the Pentecost event marked the birth of the Church.

The message is clear: Pentecost is the new Sinai; the Holy Spirit is the New Covenant; and once again there is the gift of the new Law to the Church, the New Israel. But the parallels are not just meant to be equivalent. The Christian Pentecost is meant to be the fulfilment of what was merely foreshadowed in the Old Testament - a definite upgrade. At Sinai the people were kept away from the fire on the mountain because they had not purified themselves. But at Pentecost, the fire comes into their midst through the Apostles. At Sinai, God gave the Law written by His finger on tablets of stone. At Pentecost, He gave the Law written on Tablets of the Heart. The Torah attempted to change people from the outside. The Holy Spirit changes from within.

The promise made to the prophets is thus fulfilled. We read in the prophet Jeremiah: “This is the covenant which I will make with the house of Israel after those days, says the Lord: I will put my law within them, and I will write it upon their hearts” (Jer 31:33). And in the prophet Ezekiel: “A new heart I will give you, and a new spirit I will put within you; and I will take out of your flesh the heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh. And I will put my Spirit within you, and cause you to walk in my statutes and be careful to observe my ordinances” (Ez 36:26-27).

The law of Moses pointed out obligations but could not change the human heart. A new heart was needed, and that is precisely what God offers us by virtue of the redemption accomplished by Jesus. The Father removes our heart of stone and gives us a heart of flesh like Christ’s, enlivened by the Holy Spirit who enables us to act out of love (cf. Rom 5:5). On the basis of this gift, a new Covenant is established between God and humanity. St Thomas Aquinas says with keen insight that the Holy Spirit Himself is the New Covenant, producing love in us, the fullness of the law.

This is the last and perhaps the most important of the parallels. At Sinai, after the people receive the law of the Lord, they swear a covenant with God. A covenant is how families are created. That’s the purpose of a covenant. When God swears His covenant with us, it’s to make us His family. The whole story of the Bible is a story of covenants as God is reuniting us with His family, which Adam got kicked out of. So God makes covenants with Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses and David. The Old Covenant sealed at Sinai is now replaced by the New at Pentecost. These Old Testament covenants are finally fulfilled in the New Covenant of Jesus Christ where finally the family of God isn’t only dictated by natural bloodlines, but through the blood of Jesus Christ.

The covenant of Sinai was broken by the people’s apostasy and rebellion when they demanded that Aaron make a golden calf as an object of worship, Moses ordered the Levites to slaughter the idolaters. It was said that 3,000 were killed. If you recall from the account of Pentecost in the Acts of the Apostles, how many were baptised and added to the Church on that day? 3,000. In other words, the 3,000 lost through the broken covenant at the foot of Sinai in the old Israel is restored to the New Israel – the Church - because of the New Covenant of Jesus Christ. This is the birth of the new people of God. What was dead has been brought back to life through the power of the Holy Spirit – through the sacraments.

So, there you have it. The backstory of Pentecost in the book of Acts is the scene at Sinai way back at the birth of Israel as the people of God. We are the new people of God. We are the New Israel, the restored and transformed kingdom of God in the New Covenant of Jesus Christ! Thanks be to God for the Holy Spirit! He brings us life. He manifests God in our presence. He continues the power of the resurrected and ascended Christ in our lives. It is the Spirit that gives life. The Holy Spirit brings Christ to us through the sacraments. He guides in the life of prayer. He draws us closer to our Lord so that we can fulfill our destiny as children of God. Don’t ever stop asking for the Holy Spirit.

Thursday, May 9, 2024

Put our faith in God's love

Seventh Sunday of Easter Year B

Suspicion always surrounds someone who comes late to the game. There is even an expression coined for this person: “Johnny come lately.” His success and speed in getting promoted is often envied and resented by others who have been longer and more experienced in the game. His ability to lead and perform is doubted by those placed under his care. He lacks the respect of those who should have confidence in his ability.

Today, we hear how a Johnny-come-lately candidate in the person of Matthias was elected to join the ranks of the Twelve Apostles after the defection and the suicide of Judas Iscariot. It’s always a challenge to fill the shoes of a towering great man. I would imagine that it is so much more difficult to fill the shoes of a scoundrel, a great failure, he will always be compared to the man who betrayed the Lord and be subjected to constant scrutiny so as to not repeat the same “mistake” as the earlier candidate. The early Christian community could not risk another disastrous pick. The first time it happened, it cost the life of the Master. If there should be a second time, God forbid, it would cost them the future of the Church.

It was important that the Twelve chosen by Jesus should remain at Twelve, even after the defection of Judas, for this is the number of the tribes of Israel, and the Church is the new Israel, the new People of God. What criteria should be required of Judas’ replacement? It would certainly not be impeccability, as all the Twelve had fallen and made mistakes, and not just Judas. St Peter, inspired by the Holy Spirit, set out one simple criterion for the candidate to fill the vacancy: “We must therefore choose someone who has been with us the whole time that the Lord Jesus was travelling round with us … and he can act with us as a witness to his resurrection.”

So, this was the sole criterion for choosing Matthias to fill the vacancy left by Judas’ exit. But there was also another candidate who fulfilled the criterion - Barsabbas. Before they drew lots to pick the candidate, the group prayed for guidance, proclaimed their trust in God and went on to cast lots and the lot fell on Matthias who became one of the Apostles. Despite, the commendation to God in prayer, it is important to note that the method of choice of the twelfth member is itself significantly deficient - drawing lots does appear to leave everything to chance just as one would seek direction from God by flipping the pages of the Bible and allowing your eyes to fall on the first words of the text that is presented to you. This has less to do with faith than it is to believing in some form of divination. We need to remember that the Holy Spirit has not yet come upon the members of the community at Pentecost to fill their minds and hearts and so enable them to select the twelfth member in a way that is both human and inspired.

Now, does this mean that after Pentecost the election of a bishop or even a Pope, who are successors of the Apostles, is always a candidate chosen directly by the Holy Spirit? This is a common question asked by many especially when they have doubts over the choice of the successful candidate. The answer, of course, is that the Holy Spirit was doing what He is always doing, prompting all involved to cast their votes for the good of the Church. But the Holy Spirit does not choose the pope; that is left to the vagaries of men, and the vagaries of their response to grace. Sometimes His grace is accepted and sometimes it is rejected. God does not impose His will on our freedom to choose.

What does this mean? The Holy Spirit does not arrange the votes so that the best possible candidate is elected. In other words, it is not divinely rigged! The Holy Spirit does not guarantee that the best candidate would be elected bishop or pope. To believe that there is such a guarantee is simply naive and chooses to ignore factual history that we’ve had many deficient candidates and scandalously bad bishops and popes. Although there is no guarantee whatsoever that the choice will reflect God’s active will, the choice of a particular man as pope obviously fits within God’s permissive will.

Happily, the Catholic Church enjoys some Divine guarantees. Christ promised to be with the Church to the end of time, and that the gates of hell would not prevail against her. This means essentially that the Holy Spirit will not permit the Church’s Divine constitution to be lost, that the fullness of all the means of salvation will always be available in the Church, that the Church’s sacraments will always be powerful sources of grace, that the Church’s Magisterial teachings will be free from error, and that the Church will remain the mystical body of Christ under the headship of our Lord Himself, as represented by His Vicar, Peter’s successor.

In the gospel, we see our Lord interceding on behalf of His disciples and the Church, praying that her members will remain united, that they will remain true to God’s name which is His will, that they would be consecrated to the truth, and none be lost. Though our Lord assures us and guarantees that He would be interceding on our behalf as the perfect High Priest, there is no guarantee that what He prayed for would always be realised because of man’s free will. Our rebellion against His divine will is evidenced by centuries of schism, apostasy and heresy, where many including Church leaders have worked against the unity of the Church and distorted her teachings by substituting it with erroneous interpretations.

With Pope Francis’ recent revelation that there were human machinations and lobbying among the cardinals during the conclave which elected his predecessor, Pope Benedict XVI, where does that leave us? Scandalised or disillusioned? Has the Holy Spirit taken a backseat? Never. We must remember and believe that the Holy Spirit is continuously active and certainly knows what He is doing—even when His graces are refused and His plans thwarted by ambitious sinful men. We must humbly acknowledge that none of us can see the future or the whole picture but God can, and God does! We must be assured and find consolation in knowing that the Holy Spirit does not tire, nor does Christian hope disappoint. Our job is to pray, work and trust in Divine Providence!

Although we may sometimes doubt the wisdom of our leaders and why they were chosen, we must never ever doubt God’s wisdom in allowing these men to be elected and chosen. As St John in the second reading exhorts us, let us “put our faith in God’s love towards ourselves. God is love and anyone who lives in love lives in God, and God lives in him.” (1 John 15-16)

Suspicion always surrounds someone who comes late to the game. There is even an expression coined for this person: “Johnny come lately.” His success and speed in getting promoted is often envied and resented by others who have been longer and more experienced in the game. His ability to lead and perform is doubted by those placed under his care. He lacks the respect of those who should have confidence in his ability.

Today, we hear how a Johnny-come-lately candidate in the person of Matthias was elected to join the ranks of the Twelve Apostles after the defection and the suicide of Judas Iscariot. It’s always a challenge to fill the shoes of a towering great man. I would imagine that it is so much more difficult to fill the shoes of a scoundrel, a great failure, he will always be compared to the man who betrayed the Lord and be subjected to constant scrutiny so as to not repeat the same “mistake” as the earlier candidate. The early Christian community could not risk another disastrous pick. The first time it happened, it cost the life of the Master. If there should be a second time, God forbid, it would cost them the future of the Church.

It was important that the Twelve chosen by Jesus should remain at Twelve, even after the defection of Judas, for this is the number of the tribes of Israel, and the Church is the new Israel, the new People of God. What criteria should be required of Judas’ replacement? It would certainly not be impeccability, as all the Twelve had fallen and made mistakes, and not just Judas. St Peter, inspired by the Holy Spirit, set out one simple criterion for the candidate to fill the vacancy: “We must therefore choose someone who has been with us the whole time that the Lord Jesus was travelling round with us … and he can act with us as a witness to his resurrection.”

So, this was the sole criterion for choosing Matthias to fill the vacancy left by Judas’ exit. But there was also another candidate who fulfilled the criterion - Barsabbas. Before they drew lots to pick the candidate, the group prayed for guidance, proclaimed their trust in God and went on to cast lots and the lot fell on Matthias who became one of the Apostles. Despite, the commendation to God in prayer, it is important to note that the method of choice of the twelfth member is itself significantly deficient - drawing lots does appear to leave everything to chance just as one would seek direction from God by flipping the pages of the Bible and allowing your eyes to fall on the first words of the text that is presented to you. This has less to do with faith than it is to believing in some form of divination. We need to remember that the Holy Spirit has not yet come upon the members of the community at Pentecost to fill their minds and hearts and so enable them to select the twelfth member in a way that is both human and inspired.

Now, does this mean that after Pentecost the election of a bishop or even a Pope, who are successors of the Apostles, is always a candidate chosen directly by the Holy Spirit? This is a common question asked by many especially when they have doubts over the choice of the successful candidate. The answer, of course, is that the Holy Spirit was doing what He is always doing, prompting all involved to cast their votes for the good of the Church. But the Holy Spirit does not choose the pope; that is left to the vagaries of men, and the vagaries of their response to grace. Sometimes His grace is accepted and sometimes it is rejected. God does not impose His will on our freedom to choose.

What does this mean? The Holy Spirit does not arrange the votes so that the best possible candidate is elected. In other words, it is not divinely rigged! The Holy Spirit does not guarantee that the best candidate would be elected bishop or pope. To believe that there is such a guarantee is simply naive and chooses to ignore factual history that we’ve had many deficient candidates and scandalously bad bishops and popes. Although there is no guarantee whatsoever that the choice will reflect God’s active will, the choice of a particular man as pope obviously fits within God’s permissive will.

Happily, the Catholic Church enjoys some Divine guarantees. Christ promised to be with the Church to the end of time, and that the gates of hell would not prevail against her. This means essentially that the Holy Spirit will not permit the Church’s Divine constitution to be lost, that the fullness of all the means of salvation will always be available in the Church, that the Church’s sacraments will always be powerful sources of grace, that the Church’s Magisterial teachings will be free from error, and that the Church will remain the mystical body of Christ under the headship of our Lord Himself, as represented by His Vicar, Peter’s successor.

In the gospel, we see our Lord interceding on behalf of His disciples and the Church, praying that her members will remain united, that they will remain true to God’s name which is His will, that they would be consecrated to the truth, and none be lost. Though our Lord assures us and guarantees that He would be interceding on our behalf as the perfect High Priest, there is no guarantee that what He prayed for would always be realised because of man’s free will. Our rebellion against His divine will is evidenced by centuries of schism, apostasy and heresy, where many including Church leaders have worked against the unity of the Church and distorted her teachings by substituting it with erroneous interpretations.

With Pope Francis’ recent revelation that there were human machinations and lobbying among the cardinals during the conclave which elected his predecessor, Pope Benedict XVI, where does that leave us? Scandalised or disillusioned? Has the Holy Spirit taken a backseat? Never. We must remember and believe that the Holy Spirit is continuously active and certainly knows what He is doing—even when His graces are refused and His plans thwarted by ambitious sinful men. We must humbly acknowledge that none of us can see the future or the whole picture but God can, and God does! We must be assured and find consolation in knowing that the Holy Spirit does not tire, nor does Christian hope disappoint. Our job is to pray, work and trust in Divine Providence!

Although we may sometimes doubt the wisdom of our leaders and why they were chosen, we must never ever doubt God’s wisdom in allowing these men to be elected and chosen. As St John in the second reading exhorts us, let us “put our faith in God’s love towards ourselves. God is love and anyone who lives in love lives in God, and God lives in him.” (1 John 15-16)

Monday, May 6, 2024

A Descent before an Ascent

Solemnity of the Ascension of the Lord

Lithuania Poland Pilgrimage

John Paul II Salt Chapel, Wieliczka Salt Mine

Most of you are familiar with that basic rule of gravity, “what goes up, must come down.” I guess that principle applies to us. Before taking off for the skies to fly home, we have decided to have our last Mass here in the depths of the earth, literally. But the gospel seems to have a different spin on this. In fact, it proclaims: “The One who came down, must now go up!” I guess that most of us would think of the Ascension as a “going up,” as the normal usage of the word would suggest. Few would see the Ascension as actually linked to a descent.

Salvation history takes a similar route. God, or more specifically, God in the flesh, had to touch and be touched by the rock-bottom experience of our human existence, before He can take the ascending path leading man to his redemption. St Paul lays out this paradox in the second reading. Having quoted Psalm 68 (or 67), St Paul then gives this explanation: “When it says, ‘he ascended’, what can it mean if not that he descended right down to the lower regions of the earth? The one who rose higher than all the heavens to fill all things is none other than the one who descended.” Christ is the victorious conqueror who ascends to His throne in heaven after defeating the spiritual forces. He wins this victory by descending to the very depths, even to plunge Himself into hell, to enter the fray of battle with sin, death and the devil, to accomplish this deed. Christ now shares the spoils of war with His followers. We, perennial losers because of our propensity to sin, have become winners, not by our own achievement but this was accomplished for us by the One who conquered sin and death and victoriously rose from the grave, and now sits at God’s right hand as our Champion.

In fact, it would not be an exaggeration to say that this descend-ascend V movement describes St Luke’s two volume work - his gospel and the Acts of the Apostles - which provide us with not just one, but two accounts of the Ascension. One account ends his gospel, and a second account begins the Acts of the Apostles. In each passage, the Ascension is the essential fulcrum linking the life of Jesus (the Gospels) to the life of the Church (Acts). St Luke begins his gospel with the descent of the Son of God at the Incarnation, and then concludes with His Ascension. Our Lord descended into the human realm as He was sent by the Father, in obedience to the Father’s will to save humanity and then our Lord ascends to His rightful place at the side of His Father in heaven, after having completed His mission. Venerable Fulton Sheen explains this profound connexion between these two events: “The Incarnation or the assuming of a human nature made it possible for Him to suffer and redeem. The Ascension exalted into glory that same human nature that was humbled to the death.”

This movement, however, is not just something which is undertaken by our Lord alone, but one which should be undertaken by the Apostles and all followers of the Lord too. The Collect or Opening Prayer for this Mass has this beautiful line which speaks of our common destiny: “where the Head has gone before in glory, the Body is called to follow in hope.” We must descend with Him before we can rise with Him and follow our Lord in His ascent to glory. The Apostles accompanied our Lord on His journey to Jerusalem. Before they can ascend with the Lord to the glory which He wishes to share with them, they too must descend from their high horses and acknowledge that they are part of the human dung heap of sin, cowardice, faithlessness and infidelity. This had to happen before they can be redeemed by the Lord. Just like the Lord, they needed to experience humiliation before glorification; death before Eternal Life. After the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, we see a speedy recovery. They begin to ‘ascend’ to the heights of missionary zeal, preaching the gospel of the Risen and Ascended Lord, from Judaea to Samaria and then, to the ends of the earth.

On this day, as we commemorate the Lord’s Ascension, should our gaze be directed upwards? What do we hope to see? I guess the dark cavernous ceiling of this salt mine, would be the most obvious answer. Or two feet disappearing into the clouds? Well, the two men in white (presumably angels) at the end of today’s first reading from Acts provides us with the answer, in the form of a question: “Why are you … standing here looking into the sky?”

Their question seems to be a challenge to not just be focused on one direction. In fact, we are invited to look upward, downward, and the road ahead of us. Our Lord’s Ascension invites us always to look upwards, in other words, to never lose sight of the hope of heaven, especially when navigating this world with its many pitfalls mired in disappointment and despair. We are asked to strive always for what’s higher, for what’s more noble, for what stretches us and takes us upward beyond the moral and spiritual ruts, within which we habitually find ourselves. Our Lord’s Ascension reminds us that we can be more, that we can transcend the ordinary and break through the old ceilings, that have until now constituted our horizon. His Ascension tells us that when we stretch ourselves enough, we will be able to walk on water, be great saints, be enflamed with the Spirit and experience already, the deep joys of God’s Kingdom.

But our Lord’s Ascension also invites us to look downwards. We are told to make friends with the desert, the Cross, with ashes, with self-renunciation, with humiliation, with our shadow, and with death itself. We are told that we grow not just by moving upward but also by descending downward. We grow too by letting the desert work us over, by renouncing cherished dreams and accepting the Cross, by letting the humiliations that befall us deepen our character, by having the courage to face our own deep chaos, and by making peace with our mortality. Sometimes, our task is not to raise our eyes to the heavens, but to look down upon the earth, to sit in the ashes of loneliness and humiliation, to stare down the restless desert inside us and to make peace with our human limits and our fragility.

Christians are not only asked to look upward as if our heads have disappeared in the clouds, nor should we be so focused looking downward in intense introspection to the point of despair. We must look ahead at the path which we must walk, the very same path which our Lord, fully human and fully divine, had walked before us. To look ahead, is to be reminded that we have a mission to accomplish, a gospel to be preached, a witness to give to a world that has often lost sight of looking upwards or downwards but one lost in self-absorption. At the end of every pilgrimage, this is what we must do. This may be the end of our pilgrimage to Lithuania and Poland but let us not forget that we are still on a pilgrimage of life to heaven. To look ahead to the horizon who is Christ, for “where the Head has gone before in glory, the Body is called to follow in hope.”

Lithuania Poland Pilgrimage

John Paul II Salt Chapel, Wieliczka Salt Mine

Most of you are familiar with that basic rule of gravity, “what goes up, must come down.” I guess that principle applies to us. Before taking off for the skies to fly home, we have decided to have our last Mass here in the depths of the earth, literally. But the gospel seems to have a different spin on this. In fact, it proclaims: “The One who came down, must now go up!” I guess that most of us would think of the Ascension as a “going up,” as the normal usage of the word would suggest. Few would see the Ascension as actually linked to a descent.

Salvation history takes a similar route. God, or more specifically, God in the flesh, had to touch and be touched by the rock-bottom experience of our human existence, before He can take the ascending path leading man to his redemption. St Paul lays out this paradox in the second reading. Having quoted Psalm 68 (or 67), St Paul then gives this explanation: “When it says, ‘he ascended’, what can it mean if not that he descended right down to the lower regions of the earth? The one who rose higher than all the heavens to fill all things is none other than the one who descended.” Christ is the victorious conqueror who ascends to His throne in heaven after defeating the spiritual forces. He wins this victory by descending to the very depths, even to plunge Himself into hell, to enter the fray of battle with sin, death and the devil, to accomplish this deed. Christ now shares the spoils of war with His followers. We, perennial losers because of our propensity to sin, have become winners, not by our own achievement but this was accomplished for us by the One who conquered sin and death and victoriously rose from the grave, and now sits at God’s right hand as our Champion.

In fact, it would not be an exaggeration to say that this descend-ascend V movement describes St Luke’s two volume work - his gospel and the Acts of the Apostles - which provide us with not just one, but two accounts of the Ascension. One account ends his gospel, and a second account begins the Acts of the Apostles. In each passage, the Ascension is the essential fulcrum linking the life of Jesus (the Gospels) to the life of the Church (Acts). St Luke begins his gospel with the descent of the Son of God at the Incarnation, and then concludes with His Ascension. Our Lord descended into the human realm as He was sent by the Father, in obedience to the Father’s will to save humanity and then our Lord ascends to His rightful place at the side of His Father in heaven, after having completed His mission. Venerable Fulton Sheen explains this profound connexion between these two events: “The Incarnation or the assuming of a human nature made it possible for Him to suffer and redeem. The Ascension exalted into glory that same human nature that was humbled to the death.”

This movement, however, is not just something which is undertaken by our Lord alone, but one which should be undertaken by the Apostles and all followers of the Lord too. The Collect or Opening Prayer for this Mass has this beautiful line which speaks of our common destiny: “where the Head has gone before in glory, the Body is called to follow in hope.” We must descend with Him before we can rise with Him and follow our Lord in His ascent to glory. The Apostles accompanied our Lord on His journey to Jerusalem. Before they can ascend with the Lord to the glory which He wishes to share with them, they too must descend from their high horses and acknowledge that they are part of the human dung heap of sin, cowardice, faithlessness and infidelity. This had to happen before they can be redeemed by the Lord. Just like the Lord, they needed to experience humiliation before glorification; death before Eternal Life. After the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, we see a speedy recovery. They begin to ‘ascend’ to the heights of missionary zeal, preaching the gospel of the Risen and Ascended Lord, from Judaea to Samaria and then, to the ends of the earth.

On this day, as we commemorate the Lord’s Ascension, should our gaze be directed upwards? What do we hope to see? I guess the dark cavernous ceiling of this salt mine, would be the most obvious answer. Or two feet disappearing into the clouds? Well, the two men in white (presumably angels) at the end of today’s first reading from Acts provides us with the answer, in the form of a question: “Why are you … standing here looking into the sky?”

Their question seems to be a challenge to not just be focused on one direction. In fact, we are invited to look upward, downward, and the road ahead of us. Our Lord’s Ascension invites us always to look upwards, in other words, to never lose sight of the hope of heaven, especially when navigating this world with its many pitfalls mired in disappointment and despair. We are asked to strive always for what’s higher, for what’s more noble, for what stretches us and takes us upward beyond the moral and spiritual ruts, within which we habitually find ourselves. Our Lord’s Ascension reminds us that we can be more, that we can transcend the ordinary and break through the old ceilings, that have until now constituted our horizon. His Ascension tells us that when we stretch ourselves enough, we will be able to walk on water, be great saints, be enflamed with the Spirit and experience already, the deep joys of God’s Kingdom.

But our Lord’s Ascension also invites us to look downwards. We are told to make friends with the desert, the Cross, with ashes, with self-renunciation, with humiliation, with our shadow, and with death itself. We are told that we grow not just by moving upward but also by descending downward. We grow too by letting the desert work us over, by renouncing cherished dreams and accepting the Cross, by letting the humiliations that befall us deepen our character, by having the courage to face our own deep chaos, and by making peace with our mortality. Sometimes, our task is not to raise our eyes to the heavens, but to look down upon the earth, to sit in the ashes of loneliness and humiliation, to stare down the restless desert inside us and to make peace with our human limits and our fragility.

Christians are not only asked to look upward as if our heads have disappeared in the clouds, nor should we be so focused looking downward in intense introspection to the point of despair. We must look ahead at the path which we must walk, the very same path which our Lord, fully human and fully divine, had walked before us. To look ahead, is to be reminded that we have a mission to accomplish, a gospel to be preached, a witness to give to a world that has often lost sight of looking upwards or downwards but one lost in self-absorption. At the end of every pilgrimage, this is what we must do. This may be the end of our pilgrimage to Lithuania and Poland but let us not forget that we are still on a pilgrimage of life to heaven. To look ahead to the horizon who is Christ, for “where the Head has gone before in glory, the Body is called to follow in hope.”