Eighteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

Vanity seems to be a vice that is not only confined to women but also equally plagues men. Coiffed hair, manicured nails, shiny smooth complexions that scream of repeated facials, and a wardrobe that could put Imelda Marcos’ shoe collection to shame. Vanity in this context means pride but vanity could also mean futility or the pointlessness of our actions and decisions or even life itself. The readings for today address the latter.

People often struggle with these questions, ‘What is life all about?’ ‘What is man’s purpose in this life?’ This is what the Book of Ecclesiastes seeks to address. The book is a philosophical essay attributed to Solomon, the proverbial philosopher king. The author wrote this book from the mistakes he made. He shares his own life’s search. The man had wisdom, riches, horses, armies, and women (that’s an understatement, he had lots of women). Yet, in the end Solomon declared everything to be vanity; in other word, pointless, worthless, meaningless, and purposeless. To pursue vanity is to chase after the wind. Starting with the well-known words, "Vanity of vanities, and all is vanity," and repeating them in the last chapter after having taken us through all the vanities of life, the book contains the important lesson he learns from God, in a sort of ‘roundabout’ way. The Book ends by giving us the antidote of vanity: fear of the Lord and the observance of the moral law. The secret to a purposeful life is: Without God, ‘all is vanity’. But with God, nothing is in vain.

In the gospel, we are given two examples of such earthly vanity - the greedy brother and the rich man in a parable told by the Lord. A man in the crowd puts this request to the Lord, “Master, tell my brother to give me a share of our inheritance.” The question sounds oddly familiar. I’ve seen how family battles over inheritance have set kith against kin. The law of primogeniture says (Num 27:1-11 Deut 21:15) that the first born gets a double portion. If you had two brothers, you divided the estate three ways and the oldest got two parts. So, guess which son this is. His request suggests that he’s the youngest son. Greed, envy and a sense of entitlement have blinded him to place money above kinship.

Understanding the context of the disgruntled brother sets the stage for the parable. There is a comparison and contrast going on between the two characters in the parable and two characters outside the parable. The rich man in the parable is compared to the unhappy younger brother in real life. Christ in real life acts as judge and arbiter, a role taken by God in the parable. Why is the Lord telling this parable about the rich man who had no greed to a greedy man? The Lord builds up the rich man as a good guy, a content man, someone you can easily identify with and would aspire to become. This guy is just the opposite of the disgruntled and unhappy brother. What do we learn? Both men thought that life consisted in ‘things’, that the end and purpose of their lives were the acquisition of such ‘things.’ Selfishness and self-satisfaction have blinded them to the bonds of fraternity and life’s ultimate purpose.

Both the disgruntled younger brother and the contented rich man, in their pursuit for wealth without realising that they risk losing everything in a single moment, proves the point that ‘all is vanity.’ There is a major reversal in the parable – the man who thinks himself clever is proven foolish; the rich man ends up being poor to God. Notice the poetic justice. The rich man, like the entitled brother and like so many of us, so obsessed in storing up treasures for ourselves in this place, acquiring knowledge, wealth, possessions and a list of achievements, had lost sight of the fact that our ultimate goal is our own salvation – making ourselves ‘rich in the sight of God.’ The rich man is not condemned for his wealth or even his greed. He is condemned for forgetting that the ultimate ‘end’ or purpose of his life is salvation. He had made no preparations for this. He was too busy investing in this world and that is the ultimate vanity.

This parable speaks loudly to our generation; it speaks of the purpose of life and what defines it? Have you been defining life in your career, your house, your stock portfolio, in terms of your achievements, the knowledge you possess, the popularity you’ve gained, or the assumption that you will live much longer? What is going to happen when you lose one or more of those things? What happens when you get laid off? What happens when the stock market crashes? What happens when you get some disease which takes away your physical ability? What happens when your friends leave you? What happens if another pandemic hits again? If you define life according to these things, you will be devastated. If these things have become the ‘end’ and purpose of your lives, the goals you are ultimately pursuing, the treasures you are seeking for, then the diagnosis is terminal – vanity of vanities, all is vanity!

St Thomas Aquinas teaches that the real end for which man is made is to be reunited with the goodness of God through virtuous behaviour as well as the use of reason in order to know and love God above all. In the words of St Augustine, “that is our final good, which is loved for its own sake, and all other things for the sake of it.” St Ignatius Loyola in setting out the First Principle and Foundation in his Spiritual Exercises writes, “The human person is created to praise, reverence, and serve God Our Lord, and by doing so, to save his or her soul. All other things on the face of the earth are created for human beings in order to help them pursue the end for which they are created. It follows from this that one must use other created things, in so far as they help towards one's end, and free oneself from them, in so far as they are obstacles to one's end.” Thus, the riches of this life are only potentially good. Their goodness is actualised when they serve the greater good – the glory of God and love of neighbour.

The irony we face is that many people would prefer to love the means rather than the end. Man need not just love bad things in order to be condemned to hell. As the old adage teaches us, “The road to hell is lined with good intentions.” Man can pervert his ultimate end by loving seemingly good things, which seem to bring happiness, and mistake these things for the actual, infinite source of happiness - God. Whenever we choose the lesser goods over the greater Good, whenever we convert the means into the end, whenever our vision is obscured to see beyond what lies immediately before us, then we are in trouble. Everything comes down to the choice: do we choose these things as a means to the end, or do we choose them as a substitute for the end?

Today, the readings challenge us to seek the Source of all Goodness, and not just the goods He dispenses. Desire the God of Miracles, not just hunger for the miracles of God. Long for the giver and not just the gifts. Our thoughts should be on the ultimate prize: Heaven. Things of this earth either lead us to that prize, or they may distract us from that and therefore should be placed in their proper place. When we trudge the road of happy destiny, we must remember that the road is just a means to an end and not the destination itself. Anything else is VANITY!

Tuesday, July 29, 2025

Without God, all is vanity

Labels:

Humility,

parable,

pride,

Repentance,

Sin,

Sunday Homily,

vanity,

vice,

Wisdom

Monday, July 21, 2025

We dare to say

Seventeenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

The prayer of Abraham in the first reading stands in contrast to that of our Lord’s in the gospel. If Abraham struggled to find the words to intercede on behalf of the depraved inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah and even attempts to haggle and bargain with God in making a deal, our Lord provides us with the blue print of prayer in the gospel. There is no longer any need on our part to haggle with God or broker a deal like an astute lawyer, businessman or politician. God, the party on the other end of the transaction (if you see prayer as transactional), is already disclosing to us all His cards and the key to winning His favour and acquiescence.

Although what we’ve just read and heard is a different and shorter version of the Lord’s Prayer which we pray at every Mass and in our devotions, it doesn’t tamper the radical demands which we make of God. In fact, the prayer has the audacity of making the following demands of God: we demand intimacy and familiarity with God’s person and name that borders on the contemptuous and blasphemous, we demand the coming of the kingdom, we demand the terra-forming of our trouble ridden earth so that it may become more like a trouble free heaven, we demand daily sustenance from on high, we demand that our sins be forgiven, and finally we demand shelter from temptation and deliverance from evil. If the school of hard knocks has taught us anything, it would be this: never make unreasonable demands, don’t expect the impossible. Well, for man all these may seem impossible; but for God, everything’s possible! We shouldn’t, therefore, feel uncomfortable or embarrassed to recite this prayer, as it is the Lord Himself who teaches us to do so!

This point is recognised in the introduction spoken by the priest at every Mass before the community recites in unison the Lord’s Prayer, "At the Saviour's command and formed by divine teaching, we dare to say..." The phrase ‘we dare to say’ inherently recognises our insignificance before the Father. We are humbly admitting that it has nothing to do with us, in fact, it admits that it is not even something which we can ever hope to accomplish. The words convey a profound sense of unworthiness; we are in no position to make any claims or demands.

The whole phrase places the Lord’s Prayer in a different light – it is no longer to be seen as a cry of entitlement, a demand made on God to fulfill our petitions and wishes. But rather, it is a prayer of humility by someone truly unworthy to even stand before the august presence of God and yet dare to address Him with the familiar “daddy” and make a series of demands of Him. The catechism tells us that “Our awareness of our status as slaves would make us sink into the ground and our earthly condition would dissolve into dust, if the authority of our Father Himself and the Spirit of his Son had not impelled us to this cry . . . ‘Abba, Father!’ . . . When would a mortal dare call God ‘Father,’ if man’s innermost being were not animated by power from on high?” It is by placing ourselves into the position of a child, calling God our Father, that we open ourselves to the grace by which we approach God with the humble boldness of a little child.

This is how we should approach prayer. It should neither be some arcane magical formula that forces the hand of God nor just a mechanical and superficial repetition of words just to appease Him. Prayer should always be rooted in a father-child relationship where the child trusts that the father will always have his best interest in mind even if he doesn’t always get want he wants. The supplicant who comes before God doesn’t need to approach Him as a lawyer who comes before the judge, hoping to outwit and win an argument with the latter. He already knows that the Supreme Judge will always stand with Him and even stand in His place to take the punishment which he deserves.

There is a Latin maxim that addresses the centrality and priority of prayer in the life, identity and mission of the Church; “Lex Orandi, Lex Credendi, Lex Vivendi”, the law of prayer reflects the law of faith which determines the law of life. Too often it is the other way around. Our lifestyle choices force our beliefs to conform to them and thereafter affect the way we pray. But when it comes to us Christians, everything begins with prayer. Our lives must be conformed to prayer and not the other way. How we worship and pray not only reveals and guards what we believe but guides us in how we live our Christian faith and fulfill our Christian mission in the world. As much as we are sometimes taken up with the spontaneity of the praying style of our Protestant brethren, and many of us too are tempted to venture into some innovative and creative explorations on our own, we must always remember that the best prayer, or as St Thomas Aquinas reminds us, the most Perfect Prayer, is still the prayer not formulated by any human poet or creative genius but by Christ, the Son of God Himself. In a way, God provides us the words to speak to Him.

Thus, our ability to pray in this way can only come to us by the grace of God - it is only because our Saviour has commanded it and because we have been formed by divine teaching, that ‘we dare to say.’ There is no arrogant audacity in the tone of our voice or the content of our prayer. We take no credit for this prayer. All glory goes to God and to His Christ, Jesus our Lord. We are not the natural sons and daughters of the Heavenly Father. We have no right to address Him by this familiar name. All our words seem banal and fall empty in the light of the pre-existent Word. But because of Jesus through baptism, I have become an adopted child. The Father is revealed to us by His Son and we can approach Him only through the Son. Because of Jesus, my prayer now derives an amazing and miraculous efficacy. For that reason, we dare to call God “Our Father.” Through this prayer, the unapproachable God becomes approachable. The unknown God is made known. The strange and unfamiliar God becomes familiar and a friend. The prayer unspoken is already answered!

The prayer of Abraham in the first reading stands in contrast to that of our Lord’s in the gospel. If Abraham struggled to find the words to intercede on behalf of the depraved inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah and even attempts to haggle and bargain with God in making a deal, our Lord provides us with the blue print of prayer in the gospel. There is no longer any need on our part to haggle with God or broker a deal like an astute lawyer, businessman or politician. God, the party on the other end of the transaction (if you see prayer as transactional), is already disclosing to us all His cards and the key to winning His favour and acquiescence.

Although what we’ve just read and heard is a different and shorter version of the Lord’s Prayer which we pray at every Mass and in our devotions, it doesn’t tamper the radical demands which we make of God. In fact, the prayer has the audacity of making the following demands of God: we demand intimacy and familiarity with God’s person and name that borders on the contemptuous and blasphemous, we demand the coming of the kingdom, we demand the terra-forming of our trouble ridden earth so that it may become more like a trouble free heaven, we demand daily sustenance from on high, we demand that our sins be forgiven, and finally we demand shelter from temptation and deliverance from evil. If the school of hard knocks has taught us anything, it would be this: never make unreasonable demands, don’t expect the impossible. Well, for man all these may seem impossible; but for God, everything’s possible! We shouldn’t, therefore, feel uncomfortable or embarrassed to recite this prayer, as it is the Lord Himself who teaches us to do so!

This point is recognised in the introduction spoken by the priest at every Mass before the community recites in unison the Lord’s Prayer, "At the Saviour's command and formed by divine teaching, we dare to say..." The phrase ‘we dare to say’ inherently recognises our insignificance before the Father. We are humbly admitting that it has nothing to do with us, in fact, it admits that it is not even something which we can ever hope to accomplish. The words convey a profound sense of unworthiness; we are in no position to make any claims or demands.

The whole phrase places the Lord’s Prayer in a different light – it is no longer to be seen as a cry of entitlement, a demand made on God to fulfill our petitions and wishes. But rather, it is a prayer of humility by someone truly unworthy to even stand before the august presence of God and yet dare to address Him with the familiar “daddy” and make a series of demands of Him. The catechism tells us that “Our awareness of our status as slaves would make us sink into the ground and our earthly condition would dissolve into dust, if the authority of our Father Himself and the Spirit of his Son had not impelled us to this cry . . . ‘Abba, Father!’ . . . When would a mortal dare call God ‘Father,’ if man’s innermost being were not animated by power from on high?” It is by placing ourselves into the position of a child, calling God our Father, that we open ourselves to the grace by which we approach God with the humble boldness of a little child.

This is how we should approach prayer. It should neither be some arcane magical formula that forces the hand of God nor just a mechanical and superficial repetition of words just to appease Him. Prayer should always be rooted in a father-child relationship where the child trusts that the father will always have his best interest in mind even if he doesn’t always get want he wants. The supplicant who comes before God doesn’t need to approach Him as a lawyer who comes before the judge, hoping to outwit and win an argument with the latter. He already knows that the Supreme Judge will always stand with Him and even stand in His place to take the punishment which he deserves.

There is a Latin maxim that addresses the centrality and priority of prayer in the life, identity and mission of the Church; “Lex Orandi, Lex Credendi, Lex Vivendi”, the law of prayer reflects the law of faith which determines the law of life. Too often it is the other way around. Our lifestyle choices force our beliefs to conform to them and thereafter affect the way we pray. But when it comes to us Christians, everything begins with prayer. Our lives must be conformed to prayer and not the other way. How we worship and pray not only reveals and guards what we believe but guides us in how we live our Christian faith and fulfill our Christian mission in the world. As much as we are sometimes taken up with the spontaneity of the praying style of our Protestant brethren, and many of us too are tempted to venture into some innovative and creative explorations on our own, we must always remember that the best prayer, or as St Thomas Aquinas reminds us, the most Perfect Prayer, is still the prayer not formulated by any human poet or creative genius but by Christ, the Son of God Himself. In a way, God provides us the words to speak to Him.

Thus, our ability to pray in this way can only come to us by the grace of God - it is only because our Saviour has commanded it and because we have been formed by divine teaching, that ‘we dare to say.’ There is no arrogant audacity in the tone of our voice or the content of our prayer. We take no credit for this prayer. All glory goes to God and to His Christ, Jesus our Lord. We are not the natural sons and daughters of the Heavenly Father. We have no right to address Him by this familiar name. All our words seem banal and fall empty in the light of the pre-existent Word. But because of Jesus through baptism, I have become an adopted child. The Father is revealed to us by His Son and we can approach Him only through the Son. Because of Jesus, my prayer now derives an amazing and miraculous efficacy. For that reason, we dare to call God “Our Father.” Through this prayer, the unapproachable God becomes approachable. The unknown God is made known. The strange and unfamiliar God becomes familiar and a friend. The prayer unspoken is already answered!

Saturday, July 12, 2025

The Gold Standard of Hospitality

Sixteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

Heaven in popular imagination invokes a brightly lit realm above the clouds, a realm devoid of walls, private spaces or homes, where the heavenly denizens are free to roam and wander at will with no one complaining about another invading their private space. But our Lord’s own description seems far from this: “In my Father’s house are many rooms. If it were not so, would I have told you that I go to prepare a place for you?” (John 14:2) At one level, the Jews who first heard these words would have thought immediately of the Temple. If God was indeed Jesus’ father, the Temple which is God’s House (literally this is what the Hebrew word “Bethel” meant) is the “Father’s house” which our Lord is referring to in this text. The Temple of Jerusalem was indeed made up of several rooms or spaces and the closer you get to the inner sanctum of the Temple, the more groups of people would be excluded. For all purposes, it was not a very welcoming or hospitable house.

So, our Lord’s reference to the “Father’s house” which He was returning to, the house with “many rooms”, the house where He was preparing a place to welcome us, could not possibly be referring to this building. In the year 70 AD, after the siege of Jerusalem, the Temple would be destroyed by the Romans, the Jews would be dispersed to the far corners of the empire, and they would be a homeless and stateless nation as once their ancestors were in Egypt and later in Babylon. For our Lord, the true home which He was preparing, would not just be a place to visit, but one to stay. It would be a “dwelling place.”

This is at the heart of God’s hospitality that we encounter in today’s set of readings. The first reading and the gospel provides us with two stellar examples of hospitality - Abraham and Martha. But there is a twist to the ending of both tales demonstrating that as much as we wish to offer hospitality to others and to God, it is we who are the real beneficiaries of hospitality, especially of God’s.

The first reading is not just a story of Abraham’s hospitality offered to his visitors, but more importantly, it is the hospitality offered by the three visitors, which Christians would later identify as the Most Holy Trinity, to Abraham. Our attention is usually focused on the acts of hospitality which Abraham shows to his guests, but are we correct in doing so? The ending of the story which tells us how the three guests would bless Abraham and his seemingly barren wife, both in their old age, with a child, should be the key that unlocks the secret of this tale.

When Abraham gives his guests water, who really gives the water of life? When Abraham refreshes them by washing their feet, who really makes who clean? And when Abraham offers them bread, who really gives the bread of life? If you can figure out this riddle, you are one step closer to enlightenment. I’ll give you a clue… it isn’t Abraham who is the giver of all gifts. This isn’t a story about ordinary hospitality. And neither is the Gospel reading too. It wasn’t Abraham who was really being hospitable. It was God, God giving Abraham the bread of life and the water of life and the washing of salvation.

We turn our attention to the gospel. In wanting to show hospitality to the Lord, Martha expresses hostility towards her own sister whom she believes is unsympathetic to her hard work in the kitchen. For Martha, the “better part" of hospitality is to make her guest feel welcomed, accepted, and loved. Many of us would agree with her.

But our Lord by pointing to the action of Mary shows us that the “better part” is to sit at His feet and listen to His life-giving Word. The best hospitality we can give to the Lord is to listen to Him, which is another way of saying, to accept His hospitality.

Throughout scriptures, it is God who offers hospitality to us. The two bookends of the Bible speak of God’s hospitality - Eden and the Heavenly Jerusalem, both representative of God’s desire to dwell with us and among us. Everything that comes in-between shows God’s unwavering attempt to draw estranged fallen humanity home - whether it be through the establishment of a family of nations under the patriarchs, the call of the prophets to return to the covenants and finally the sending of His only begotten Son to save mankind.

Rather than assume that we can do something exceedingly great for God like Martha, we should imitate Mary in her docility in humbly accepting the gift of hospitality from Jesus, which is salvation. Our place is at His feet in humble adoration and submission. And unless, we recognise that our place is at His feet instead of arrogantly barking orders to others or even to God in order to get our way, our feeble attempts at hospitality would only result in more hostility. The best thing we can do for God, to please Him, is to accept His hospitality without any conditions. The astounding paradoxical truth is this: we don’t serve God. God serves us. We don’t need to feed God. God feeds us. We don’t need to provide for God. God provides for us. We don’t need to protect God. God heals and holds us in our brokenness. We don’t need to sacrifice to God. God has already sacrificed Himself for us.

Both of these apparently simple but exceedingly profound biblical stories offer a guiding word to Christians who yearn and thirst for hospitality, as we struggle to offer the warmth of hospitality to others. At this and every Eucharist, God invites us to the altar of His perfect sacrifice, to the meal which is a foretaste of the heavenly banquet, to have a seat at the table and share in the fellowship of the Most Holy Trinity. It is here where we will be fed, we will be refreshed, and where we are saved. As we nervously approach the altar, fully aware of our unworthiness, we hear the Lord who beckons to us, as how He had gently spoken to Abraham, Mary and Martha: “Come… sit down… and taste. Fret no longer in what you can do but pay attention to what I can do for you. With me you will learn love. With me you will discover life. With me you will find a most welcoming eternal home.” If we have received such astounding hospitality at the hands of God, it should not be difficult for us to share a fraction of that with others. Remember: “You received without charge, give without charge.”

Labels:

Evangelisation,

heaven,

hospitality,

Providence,

salvation,

Sunday Homily

Monday, July 7, 2025

How have we come to salvation?

Fifteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

Whenever an anecdotal story is shared, it begs the question: “what’s the moral of the story?” Most homilies on the parable of the Good Samaritan would most likely attempt to provide the answer to this question and it would often sound like this: “do good to others, even those who are not your friends.” If it was only that simple, this would be the end of my homily. But the truth is that there is more than meets the eye in this most familiar parable of our Lord.

The context of our Lord telling this parable is that it serves as an answer given to a question posed by a lawyer, not to be confused with modern advocates and solicitors. The lawyer here is also known as a scribe, an academician or scholar, who has devoted his life to studying the Mosaic Law in order to provide a correct interpretation and application of the Law to the daily lives of fellow Jews. The question he poses is not just a valid question but one of utmost importance because it has to do with our ultimate purpose in life: “Master, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” That is the question that every religion and every philosophy has ever attempted to answer. Though a valid question and one which all of us should want to know the answer, the evangelist tells us that his motives are less than pure. It is said that he asked this question “to disconcert” the Lord. It was a trap. In fact, the lawyer already knows the answer to his question. But knowledge of the answer does not necessarily mean that one is living the answer, which is what the Lord wishes to expose here. He speaks eloquently of love but has no love for our Lord or even his audience. And so our Lord tells him that even though he has answered right by citing the two-fold commandments of love, there is still something missing in his answer: “do this and life is yours.”

Having been found out by the Lord and therefore, humiliated, he continues to try to “justify” himself by nit-picking: “And who is my neighbour?” In other words, the lawyer seeks to corner Jesus by forcing Him to tell who is deserving of our love. The surprising thing about the parable of the Good Samaritan is that it does not really provide a direct answer to the lawyer’s second question of defining one’s neighbour. If Jesus had been asked, “How should we treat our neighbours?” and had responded with this story, perhaps “Be like the Good Samaritan” would be an acceptable interpretation. Such a moralistic interpretation would mean that the “neighbour” in question is not the one who is deserving of our love but the one who demonstrates love. It turns the question completely around. But, the intention of the parable is more than a mere call to display altruistic behaviour to one’s neighbour. It addressed a more vital question: how have we come to salvation?

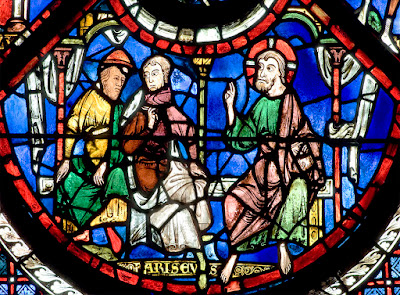

According to the Fathers of the Church, this parable is as an impressive allegory of the fall and redemption of all mankind – how we came to be saved! This is clearly depicted in a beautiful stained-glass window in the famous 12th-century cathedral in Chartres, France. This window is divided into two parts. At the upper section of the window, we see the story of Adam and Eve's expulsion from the Garden of Eden, at the bottom section of the window, the parable of the Good Samaritan; therefore, the narrative of the creation and fall of man is juxtaposed with that of the Good Samaritan. What does the parable of the Good Samaritan have to do with the Fall of Adam and Eve? Where did this association originate?

The roots of this allegorical interpretation reach deeply into the earliest Christian Tradition. Various Fathers of the Church saw Jesus Himself in the Good Samaritan; and in the man who fell among thieves they saw Adam, a representative of mankind, our very humanity wounded and disoriented on account of its sins. For example, Origen employed the following allegory: Jerusalem represents heaven; Jericho, the world; the robbers, the devil and his minions; the Priest represents the Law, and the Levite the Prophets; the Good Samaritan, Christ; the ass, Christ’s body carrying fallen man to the inn which becomes the Church. Even the Samaritan’s promise to return translates into Christ’s triumphant return at the Parousia.

Understanding this parable allegorically adds an eternal perspective and value to its message. It certainly takes it beyond the cliché ‘moral of the story’: ‘Be a Good Samaritan.’ Before we can become Good Samaritans to help others, we need to remember that we have been saved by the Good Samaritan – the story helps us become aware of where we have come from, how we have fallen into our present state through sin, and how Christ has come to save us, the Sacraments of grace continue to sanctify us and the Church continues to nurture and heal us. In other words, this Christological interpretation shifts the focus from man to God: from ‘justification’, how do we work out our salvation, to sanctification, how does Christ save us and continue to sanctify us. As the old patristic adage affirms: “God became Man so that men may become gods.” It moves us away from the humanistic mode of being saviours of the world to a more humble recognition that we are indeed in need of salvation ourselves - we are that fallen man by the wayside waiting for a Saviour and we have found Him in Christ!

In a rich irony, we move from being identified with the priest and the Levite who were solely concerned over their personal salvation but never perfectly love others “as ourselves,” much less our enemies, to being identified with the traveller in desperate need of salvation. The Lord intends the parable itself to leave us beaten and bloodied, lying in a ditch, like the man in the story. We are the needy, unable to do anything to help ourselves. We are the broken people, beaten up by life, robbed of hope. But then Jesus comes. Unlike the Priest and Levite, He doesn’t avoid us. He crosses the street—from heaven to earth—comes into our mess, gets His hands dirty. At great cost to Himself on the cross, He heals our wounds, covers our nakedness, and loves us with a no-strings-attached love. He carries us personally to the shelter of the Church where we find rest, where our wounds are tended and healed. He brings us to the Father and promises that His “help” is not simply a ‘one-time’ gift—rather, it’s a gift that will forever cover “the charges” we incur and will sustain us until He returns in glory.

So the parable is not just a moralistic tale of what we must do as Christians but the history of salvation in a nutshell - it tells us what Christ has done for us and continues to do for us?

The context puts the Lord’s final exhortation to “go and do the same yourself” in perspective. It puts every work of charity, gesture of kindness, expression of hospitality on our part within the greater picture of the wonderful story of salvation. The great commandment of love isn’t about some altruistic humanistic project – us saving the world. Reaching out to others, especially to those who labour under the heavy load of toil and suffering, is not just an act of goodness. It is a participation in the economy of God’s salvation – God saving the world through us and in spite of us. We can love only because we have been loved. We can only heal because we have been healed and continue to be healed by the Good Samaritan Himself, Jesus Christ. To understand what it means to love, does not mean attempting to be a ‘Good Samaritan.’ To understand what it means to love, we need to gaze upon Jesus Christ, He is the ‘Good Samaritan’ who has laid down His life and atoned for our sins. This is eternal life!

Whenever an anecdotal story is shared, it begs the question: “what’s the moral of the story?” Most homilies on the parable of the Good Samaritan would most likely attempt to provide the answer to this question and it would often sound like this: “do good to others, even those who are not your friends.” If it was only that simple, this would be the end of my homily. But the truth is that there is more than meets the eye in this most familiar parable of our Lord.

The context of our Lord telling this parable is that it serves as an answer given to a question posed by a lawyer, not to be confused with modern advocates and solicitors. The lawyer here is also known as a scribe, an academician or scholar, who has devoted his life to studying the Mosaic Law in order to provide a correct interpretation and application of the Law to the daily lives of fellow Jews. The question he poses is not just a valid question but one of utmost importance because it has to do with our ultimate purpose in life: “Master, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” That is the question that every religion and every philosophy has ever attempted to answer. Though a valid question and one which all of us should want to know the answer, the evangelist tells us that his motives are less than pure. It is said that he asked this question “to disconcert” the Lord. It was a trap. In fact, the lawyer already knows the answer to his question. But knowledge of the answer does not necessarily mean that one is living the answer, which is what the Lord wishes to expose here. He speaks eloquently of love but has no love for our Lord or even his audience. And so our Lord tells him that even though he has answered right by citing the two-fold commandments of love, there is still something missing in his answer: “do this and life is yours.”

Having been found out by the Lord and therefore, humiliated, he continues to try to “justify” himself by nit-picking: “And who is my neighbour?” In other words, the lawyer seeks to corner Jesus by forcing Him to tell who is deserving of our love. The surprising thing about the parable of the Good Samaritan is that it does not really provide a direct answer to the lawyer’s second question of defining one’s neighbour. If Jesus had been asked, “How should we treat our neighbours?” and had responded with this story, perhaps “Be like the Good Samaritan” would be an acceptable interpretation. Such a moralistic interpretation would mean that the “neighbour” in question is not the one who is deserving of our love but the one who demonstrates love. It turns the question completely around. But, the intention of the parable is more than a mere call to display altruistic behaviour to one’s neighbour. It addressed a more vital question: how have we come to salvation?

According to the Fathers of the Church, this parable is as an impressive allegory of the fall and redemption of all mankind – how we came to be saved! This is clearly depicted in a beautiful stained-glass window in the famous 12th-century cathedral in Chartres, France. This window is divided into two parts. At the upper section of the window, we see the story of Adam and Eve's expulsion from the Garden of Eden, at the bottom section of the window, the parable of the Good Samaritan; therefore, the narrative of the creation and fall of man is juxtaposed with that of the Good Samaritan. What does the parable of the Good Samaritan have to do with the Fall of Adam and Eve? Where did this association originate?

The roots of this allegorical interpretation reach deeply into the earliest Christian Tradition. Various Fathers of the Church saw Jesus Himself in the Good Samaritan; and in the man who fell among thieves they saw Adam, a representative of mankind, our very humanity wounded and disoriented on account of its sins. For example, Origen employed the following allegory: Jerusalem represents heaven; Jericho, the world; the robbers, the devil and his minions; the Priest represents the Law, and the Levite the Prophets; the Good Samaritan, Christ; the ass, Christ’s body carrying fallen man to the inn which becomes the Church. Even the Samaritan’s promise to return translates into Christ’s triumphant return at the Parousia.

Understanding this parable allegorically adds an eternal perspective and value to its message. It certainly takes it beyond the cliché ‘moral of the story’: ‘Be a Good Samaritan.’ Before we can become Good Samaritans to help others, we need to remember that we have been saved by the Good Samaritan – the story helps us become aware of where we have come from, how we have fallen into our present state through sin, and how Christ has come to save us, the Sacraments of grace continue to sanctify us and the Church continues to nurture and heal us. In other words, this Christological interpretation shifts the focus from man to God: from ‘justification’, how do we work out our salvation, to sanctification, how does Christ save us and continue to sanctify us. As the old patristic adage affirms: “God became Man so that men may become gods.” It moves us away from the humanistic mode of being saviours of the world to a more humble recognition that we are indeed in need of salvation ourselves - we are that fallen man by the wayside waiting for a Saviour and we have found Him in Christ!

In a rich irony, we move from being identified with the priest and the Levite who were solely concerned over their personal salvation but never perfectly love others “as ourselves,” much less our enemies, to being identified with the traveller in desperate need of salvation. The Lord intends the parable itself to leave us beaten and bloodied, lying in a ditch, like the man in the story. We are the needy, unable to do anything to help ourselves. We are the broken people, beaten up by life, robbed of hope. But then Jesus comes. Unlike the Priest and Levite, He doesn’t avoid us. He crosses the street—from heaven to earth—comes into our mess, gets His hands dirty. At great cost to Himself on the cross, He heals our wounds, covers our nakedness, and loves us with a no-strings-attached love. He carries us personally to the shelter of the Church where we find rest, where our wounds are tended and healed. He brings us to the Father and promises that His “help” is not simply a ‘one-time’ gift—rather, it’s a gift that will forever cover “the charges” we incur and will sustain us until He returns in glory.

So the parable is not just a moralistic tale of what we must do as Christians but the history of salvation in a nutshell - it tells us what Christ has done for us and continues to do for us?

The context puts the Lord’s final exhortation to “go and do the same yourself” in perspective. It puts every work of charity, gesture of kindness, expression of hospitality on our part within the greater picture of the wonderful story of salvation. The great commandment of love isn’t about some altruistic humanistic project – us saving the world. Reaching out to others, especially to those who labour under the heavy load of toil and suffering, is not just an act of goodness. It is a participation in the economy of God’s salvation – God saving the world through us and in spite of us. We can love only because we have been loved. We can only heal because we have been healed and continue to be healed by the Good Samaritan Himself, Jesus Christ. To understand what it means to love, does not mean attempting to be a ‘Good Samaritan.’ To understand what it means to love, we need to gaze upon Jesus Christ, He is the ‘Good Samaritan’ who has laid down His life and atoned for our sins. This is eternal life!

Labels:

creation,

Good Samaritan,

parable,

redemption,

salvation,

Sin,

Sunday Homily

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)