Monday, July 21, 2025

We dare to say

The prayer of Abraham in the first reading stands in contrast to that of our Lord’s in the gospel. If Abraham struggled to find the words to intercede on behalf of the depraved inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah and even attempts to haggle and bargain with God in making a deal, our Lord provides us with the blue print of prayer in the gospel. There is no longer any need on our part to haggle with God or broker a deal like an astute lawyer, businessman or politician. God, the party on the other end of the transaction (if you see prayer as transactional), is already disclosing to us all His cards and the key to winning His favour and acquiescence.

Although what we’ve just read and heard is a different and shorter version of the Lord’s Prayer which we pray at every Mass and in our devotions, it doesn’t tamper the radical demands which we make of God. In fact, the prayer has the audacity of making the following demands of God: we demand intimacy and familiarity with God’s person and name that borders on the contemptuous and blasphemous, we demand the coming of the kingdom, we demand the terra-forming of our trouble ridden earth so that it may become more like a trouble free heaven, we demand daily sustenance from on high, we demand that our sins be forgiven, and finally we demand shelter from temptation and deliverance from evil. If the school of hard knocks has taught us anything, it would be this: never make unreasonable demands, don’t expect the impossible. Well, for man all these may seem impossible; but for God, everything’s possible! We shouldn’t, therefore, feel uncomfortable or embarrassed to recite this prayer, as it is the Lord Himself who teaches us to do so!

This point is recognised in the introduction spoken by the priest at every Mass before the community recites in unison the Lord’s Prayer, "At the Saviour's command and formed by divine teaching, we dare to say..." The phrase ‘we dare to say’ inherently recognises our insignificance before the Father. We are humbly admitting that it has nothing to do with us, in fact, it admits that it is not even something which we can ever hope to accomplish. The words convey a profound sense of unworthiness; we are in no position to make any claims or demands.

The whole phrase places the Lord’s Prayer in a different light – it is no longer to be seen as a cry of entitlement, a demand made on God to fulfill our petitions and wishes. But rather, it is a prayer of humility by someone truly unworthy to even stand before the august presence of God and yet dare to address Him with the familiar “daddy” and make a series of demands of Him. The catechism tells us that “Our awareness of our status as slaves would make us sink into the ground and our earthly condition would dissolve into dust, if the authority of our Father Himself and the Spirit of his Son had not impelled us to this cry . . . ‘Abba, Father!’ . . . When would a mortal dare call God ‘Father,’ if man’s innermost being were not animated by power from on high?” It is by placing ourselves into the position of a child, calling God our Father, that we open ourselves to the grace by which we approach God with the humble boldness of a little child.

This is how we should approach prayer. It should neither be some arcane magical formula that forces the hand of God nor just a mechanical and superficial repetition of words just to appease Him. Prayer should always be rooted in a father-child relationship where the child trusts that the father will always have his best interest in mind even if he doesn’t always get want he wants. The supplicant who comes before God doesn’t need to approach Him as a lawyer who comes before the judge, hoping to outwit and win an argument with the latter. He already knows that the Supreme Judge will always stand with Him and even stand in His place to take the punishment which he deserves.

There is a Latin maxim that addresses the centrality and priority of prayer in the life, identity and mission of the Church; “Lex Orandi, Lex Credendi, Lex Vivendi”, the law of prayer reflects the law of faith which determines the law of life. Too often it is the other way around. Our lifestyle choices force our beliefs to conform to them and thereafter affect the way we pray. But when it comes to us Christians, everything begins with prayer. Our lives must be conformed to prayer and not the other way. How we worship and pray not only reveals and guards what we believe but guides us in how we live our Christian faith and fulfill our Christian mission in the world. As much as we are sometimes taken up with the spontaneity of the praying style of our Protestant brethren, and many of us too are tempted to venture into some innovative and creative explorations on our own, we must always remember that the best prayer, or as St Thomas Aquinas reminds us, the most Perfect Prayer, is still the prayer not formulated by any human poet or creative genius but by Christ, the Son of God Himself. In a way, God provides us the words to speak to Him.

Thus, our ability to pray in this way can only come to us by the grace of God - it is only because our Saviour has commanded it and because we have been formed by divine teaching, that ‘we dare to say.’ There is no arrogant audacity in the tone of our voice or the content of our prayer. We take no credit for this prayer. All glory goes to God and to His Christ, Jesus our Lord. We are not the natural sons and daughters of the Heavenly Father. We have no right to address Him by this familiar name. All our words seem banal and fall empty in the light of the pre-existent Word. But because of Jesus through baptism, I have become an adopted child. The Father is revealed to us by His Son and we can approach Him only through the Son. Because of Jesus, my prayer now derives an amazing and miraculous efficacy. For that reason, we dare to call God “Our Father.” Through this prayer, the unapproachable God becomes approachable. The unknown God is made known. The strange and unfamiliar God becomes familiar and a friend. The prayer unspoken is already answered!

Monday, May 26, 2025

Worship and Mission

It is significant that St Luke tells the story of the Ascension twice, and we have the benefit of hearing both accounts today – the account from the Acts of the Apostles in the first reading, and a second account in the Gospel. Each narration brings out a different aspect of the truth but the theme of witnessing seems to bind both Lucan accounts. For St Luke, the Ascension was a significant moment in the disciples’ personal transformation. It marked a critical turning point, the passing of the Lord’s message and mission to His disciples.

In the Acts account, just before He ascends, the Lord promises His Apostles, “you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you, and then you will be my witnesses not only in Jerusalem but throughout Judaea and Samaria, and indeed to the ends of the earth.” Similarly in the Gospel, having reiterated the kerygma, the kernel of the Christian faith, that “Christ would suffer and on the third day rise from the dead,” the Lord gives them this commission: “In His name repentance for the forgiveness of sins would be preached to all the nations, beginning from Jerusalem. You are witnesses to this.” In other words, when Christ ascended, He left with the intention that the Church takes up where He left off.

The Acts version of the event also paints a rather comical scene should it be depicted in art. In my recent trip to Spain, I encountered a piece of iconography which seems strange and unique to our times but was quite prevalent during the Middle Ages to depict the Ascension of the Lord. The Apostles are gathered in this scene. Nothing unusual about this. But they are gazing up to see a pair of feet sticking out from the cover of clouds above their heads.

They would have continued staring if not shaken out of their stupor by the question posed by two men in white, presumably angels: “Why are you men from Galilee standing here looking into the sky?” The question could be paraphrased, “Do you not have something better to do than to stand here and gawk?”

Here lies one of the greatest challenges to Catholics – our inertia to engage in mission. We seem to be transfixed firmly in our churches but feel no need or urgency to reach out. We Catholics have been “indoctrinated” to attend Mass every Sunday and on holy days of obligation. The Liturgy is supposed to be the “source and summit of the Christian life.” So, we should see it not just as an end but also as a starting point for mission. Yes, worship is our primary activity. But what about mission? It is a false dichotomy to pit worship against mission. It’s never a hard choice between the two. Both worship and mission are part of the life of a Christian. They feed off each other.

The Ascension reminds us that the Church is an institution defined by mission. Today all institutions have a statement of mission; but to say the Church is defined by mission is to say something more. The Church is not an institution with a mission, but a mission with an institution. As Pope Francis of happy memory is fond of reminding us - the church exists for mission. To be sent, is the church's raison d'être, so when it ceases to be sent, it ceases to be the Church. When the Church is removed from its mission, she ends up becoming a fortress or a museum. She keeps things safe and predictable and there is a need for this – we need to be protected from the dangers of the world and from sin. But if her role is merely “protective” she leaves many within her fold feeling stranded in a no man's land, between an institution that seems out of touch and a complex world they feel called to understand and influence.

On the other hand, the Church cannot only be defined by her mission alone, but also by her call to worship the One who has sent her on this mission. If this was not the case, she would be no better than an NGO. As the Church of the Ascension is drawn upward in worship, she is also pushed outward in mission. These are not opposing movements, and the Ascension forbids such a dichotomy. The Church does not have to choose whether it will be defined by the depth of its liturgy or prayer life, or its faithfulness and fervour in mission. Both acts flow from the single reality of the Ascension. Both have integrity only in that they are connected to one another.

At the end of every Mass, the priest dismisses the faithful with one of these formulas, “Go forth, the Mass is ended!” “Go and announce the Gospel of the Lord!” etc. Mission is at the core of each of these formulas. The Sacrifice of the Mass is directed and geared towards this purpose – the continuation of the mission of Christ. If worship is the beginning of mission, then mission too must find its ultimate conclusion in worship – for the liturgy is the “source and summit of the Christian life” as taught by the Second Vatican Council. The Ascension event reminds us that mission must always be anchored in Christ through prayer. So, the more authentically missionary a church becomes, the more profound will be her life of worship, since mission always ends in worship.

The Lord has ascended to heaven and is now seated at the right hand of His Heavenly Father. But this does not mean that He is now retired or has completely withdrawn from the mission of the Church. He continues to act through the Church, through the sacraments which He had given to the Church. The Eucharistic Lord continues to invite us, He commands us, to share in His mission, and to preach the Gospel everywhere. Those first Apostles took seriously our Lord’s command that they preach the Gospel to all nations, and the fact that we are Christians here today centuries later and thousands of miles away from the birth of Christianity, is positive proof of how seriously they heeded His command. From its very origins then, the Church has had an outward missionary thrust. The work Christ began here on earth, He has now entrusted to us so that we may continue. If we have truly caught on to the message of the risen and ascended Christ, we should not just stand here looking up into the skies, waiting for an answer. We are called to get going and do the job our Lord has given us to do, never forgetting that we must remain connected to Him through our worship and prayer. With the help of the promised Holy Spirit, you will be His faithful witnesses “not only in Jerusalem but throughout Judaea and Samaria, and indeed to the ends of the earth.”

Monday, October 28, 2024

Listen and See

What connects the first reading to the gospel is that fundamental Jewish statement of belief which provides us with the first part of the daily prayer of every Jew. “Sh’ma Yisrael Adonai Eloheinu Adonai echad.” “Listen, Israel: the Lord our God is the one Lord.” If one were to understand the two-fold commandment of love which follows this statement, one needs to unpack and grasp the width and depth of this profound and supreme testimony of the Jewish faith, and by extension, the Christian faith.

The Hebrew word “Shema” translated as “listen” or “hear” deserves our attention. It is no coincidence that the first of the Apostles, Simon Peter, takes his Hebrew name from this word – “Shimon”. That is irony for you. Although, Simon Peter responded to the call of our Lord by listening, it would appear that his listening was often selective and did not lead him beyond a superficial and shallow understanding of our Lord’s identity and his mission as a disciple. His listening would be impaired until he “saw” the Risen Lord with his own eyes. This seeing would complete his listening.

But let us go back to our original verb. Listening goes beyond exercising one’s auditory sense. Listening must lead to understanding and understanding to acceptance. For the Jews, it shaped both their culture and world-view. This is how Moses describes the supreme revelation on Mount Sinai: “Then the Lord spoke to you out of the fire. You heard the sound of words but saw no form; there was only a voice” (Dt 4:12). There was a profound difference between the two civilisations of antiquity that between them shaped the culture of the West: ancient Greece and ancient Israel. The Greeks were the supreme masters of the visual arts: art, sculpture, architecture and the theatre. Their culture focused on sight. Jews, as a matter of profound religious principle, were not. God, the sole object of worship, is invisible. He transcends nature. He created the universe and is therefore beyond the universe. He cannot be seen. In fact, it was strictly prohibited to make a visible representation of God.

The God of Israel reveals Himself only in speech. Yes, His presence was sometimes mediated by angelic beings and natural and supernatural phenomena like a pillar of cloud and fire, a flaming bush, lightning and thunder. But though these pointed to God’s power and sovereignty, they were never understood to be a visible manifestation of God, just signs of His presence. Therefore, the supreme religious act in Judaism is to listen. Ancient Greece, on the other hand, was a culture of the eye; ancient Israel a culture of the ear. The Greeks worshipped what they saw; Israel worshipped what they heard. We Christians, thankfully, are heirs of both culture and our liturgy perfectly expresses both paradigms. Both hearing and seeing mark the two pillars of our sacramental economy and the Holy Mass.

When God chooses to reveal Himself to us, He is revealing His will for us, He is giving us His Law. The primary meaning of the word Torah is the Law! It would seem to follow that a book of laws or commandments must have a verb that means “to obey”, for that is the whole purpose of an imperative. Yet there is no verb in biblical Hebrew that means to obey. The closest word to obedience is “listen.” Where there seems to be a lacunae in the Hebrew language, the word for “obedience” in Latin binds the two concepts - “obidere” means “to listen, to submit and to be responsible.”

Despite its intense focus on Divine commandments, the Jewish faith is not a faith that values blind, unthinking, unquestioning obedience. There is no true listening or authentic obedience, if we do not internalise the commandments. The God of revelation is also the God of creation and redemption. Therefore, when God commands us to do certain things and refrain from others, it is not because His will is arbitrary but because He cares for the integrity of the world as His work, and for the dignity of the human person as His image. He reveals His laws to us, He commands us to obey, because He loves us, and He wants us to make love the foundation of our entire being and way of behaving and relating.

This is how we must understand the two-fold commandment of love. It is insufficient that we hear the command to love God and neighbour and profess it with our lips and then claim to know it. Listening must lead to understanding and understanding lead to acceptance, but such acceptance must be shown forth in action. To prove ourselves to be good listeners, it must be “seen” in our actions.

That is why it is not enough that our Lord enunciates the commandment of love and commands us to listen. That is the theory. He then demonstrates the perfect fulfilment of this commandment through an example which can be seen - His own death and resurrection. On the cross, we hear His words of complete abandonment and obedience to the Father and on the cross, we saw the most powerful testimony and evidence of His love.

This is how we should treat the commandment of love as how the Jews treated the Shema. It is the greatest command and the first prayer a Jewish child was taught to say. God gave His people the Shema and instructed them to recite it daily, memorise it, meditate on it, teach it, instruct it, put it on their clothing and post it on the doorframes of their home. God wanted to remind them of loving God with all their heart, soul, mind and strength every time they woke up, put on their clothes and entered or left the home. It is the quintessential expression of the most fundamental belief of Judaism.

Likewise, for us Christians too. Love must be the quintessential expression of the most fundamental belief of Christianity. For the Jews, following the Law or the Torah was their way of expressing this fundamental commandment. But for us Christians, we fulfil this commandment by imitating Christ. Our Lord is essentially saying, “to follow Me is to love God and to love others.” In the Gospel of John, our Lord tells us, “A new command I give you: love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another. By this everyone will know that you are My disciples…” (John 13:34-35). The newness of this commandment is not found in its content but in its standard. Christ is the new standard. He is the Incarnation of love whom we can listen to and see. And therefore, if we wish to love God and neighbour, we should love as He did.

Saturday, August 24, 2024

God is the Author, man isn't

Being a priest, I must admit that it’s not hard to know what I must do. If I want to know what I must do, I am simply guided by sacred scripture and sacred tradition, the teachings and disciplines of the Church found in canon law, the liturgical rubrics and pastoral directories governing church discipline, structures and practices. The hard part is doing it anyway despite it being unpopular. It’s funny that whenever I do what is required of me, I’m always accused of being “rigid”! Yes, the Church’s laws, rules and rubrics provide clear unambiguous guidance and direction, but they also make room for discernment and exception-making whenever necessary. The hard part is always trying to reinvent the wheel based on personal preferences and feelings, mine as well as others. This is when the point of reference is no longer Christ or the Church, but me. If I should “follow my heart” or that of others, without any reference to Christ or the Church, I would simply be guilty of what the Lord is accusing the Pharisees in today’s gospel: “You put aside the commandment of God to cling to human traditions.”

Too many these days, including many well-intentioned pastors, feel that the teachings of the Church fall into the category of “grey area” and “ambiguity,” thus the teachings of faith and morals are relative to individuals and their respective unique situations. They have problems with doctrinal teachings on contraception, purgatory, and indulgences (just to name a few), all of which are covered and explained clearly in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. And if we should decide to defend these teachings and the laws which flow from them, we are immediately labelled as “rigid” and “seeing everything in black and white,” refusing to acknowledge that people change over the years and so the Church must learn to adapt accordingly. The final argument and last insult would be to insist that Church laws are mere “human regulations” which justifies departing from them. And since they are supposedly “man-made rules,” you can and should dispense with them as how Christ dispensed with the man-made rules and traditions of the scribes and Pharisees in today’s gospel passage. Interesting argument but seriously flawed.

Yes, it is correct to state that many of these rules are man-made, Christ made them and Christ was fully human. It was Christ Himself who instituted the Eucharist: “Do this in memory of Me”, He said at the Last Supper. “Go therefore and baptise”, He said, and it was He who included the Trinitarian baptismal formula in the rite. It was He who taught if someone should divorce his or her spouse and marry another, it would be adultery. Our Lord was the master of creating traditions! But let us not forget this little, often ignored, seldom stressed point – Christ was also fully divine – He was fully God. So, no, though there are man-made rules in the Church just like any human organisation and society, and these rules can technically be changed and have changed over the centuries, there are fundamentally certain rules set in stone, on an unbreakable and indissoluble “stone”, which is to say that they are “immutable,” they remain binding in every age and place and under any circumstances, precisely because God is the author, and man isn’t.

Alright, given the fact that divine laws can’t be changed except by God, how about all the disciplines, canon law, rules and liturgical rubrics of the Church? Aren’t these man-made? Well, just because they are “man-made” doesn’t necessarily empty them of value. Traffic laws, statutory laws, municipal by-laws, school regulations, association rules would equally fall under the same category of being “man-made.” Can you imagine a society or a world that totally departs from any law or regulation and everyone is allowed to make decisions, behave, and act upon their own whims and fancies? If you’ve ever watched one of those apocalyptic movies of a dystopian world in the not-too-distant future, you will have your answer. We will soon descend into a society of anarchy, lawlessness, violence, where justice is merely an illusion and “might is right.” The reason for this is because none of us are as sinless as the Son of God or His immaculately conceived Mother. Laws are not meant to curtail and restrict our freedom. They are meant to ensure that our rights as well as the rights of others are protected so that true freedom may be enjoyed. The Law of Christ as expounded by the Church frees us - it frees from our selfish, self-referential, sin-encrusted egos.

A more careful examination of Christ’s words in today’s passage indicate that He was not condemning human tradition, but those who place human traditions, laws, or demands before true worship of God and His will expressed in the commandments. The problem wasn’t “human traditions” but specifically “human traditions” that obscure the priority of worship and God. Man was made to worship God; it's in our very nature to do so. Every other human activity should either flow from this or should rank second to this. This is what liturgical rubrics hope to achieve. Detailed instructions for both the priest and the congregation are intended to ensure that God is ultimately worshipped and glorified in the liturgy, and not man who is to be entertained. In other words, all these “man-made” rules of the Church which, to some of us, doesn’t seem to be what Christ taught, actually flow from the heart of Christ's teaching. Christ gave us the Church to teach and to guide us; she does so, in part, by teaching us to know God, to love Him and serve Him and through all these, be united with Him in Paradise forever. But when we substitute our own will for this most basic aspect of our humanity, we don't simply fail to do what we ought; we take a step backward and obscure the image of God.

It is often very convenient to denounce Catholic tradition as “man-made” or “human tradition” just because we don’t like it. The hypocrisy of such an accusation is often lost on those who supplant the Church’s tradition, rules and rubrics, with their own interpretation and version. Clericalism, real clericalism and not just the dressed-up version of it (those who wear black cassocks or lacy albs), is the result of choosing to depart from those rules, disciplines and teachings. When we ignore or reject the rules of the Church, we are merely replacing them with our own rules, our so-called “human traditions.” In fact, we are putting “aside the commandment of God to cling to human traditions.” It is not those who keep the rules but those who flagrantly break the rules that are the modern-day Pharisees.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church tells us that Sacred Tradition, rather than a set of “man-made rules” or “human traditions” is “the living memorial of God’s Word.” Pope Benedict XVI explains that Sacred Tradition “is not the transmission of things or words, an assortment of lifeless objects; (but) it is the living stream that links us to the origins, the living stream in which those origins are ever present.” Therefore, we should be putting aside our own arrogant personal preferences and opinions, rather than God’s commandments, and come to acknowledge that it is not stupidity but humility to listen to the voice of the Church because as St Ambrose reminds us, “the Church shines not with her own light, but with the light of Christ. Her light is drawn from the Sun of Justice, so that she can exclaim: ‘It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me’ (Gal 2:20)”.

Wednesday, February 28, 2024

The New Temple

For many Catholics, fund raising can sound like a dirty word. This aversion and resistance to fund raising activities is often justified by the following assumptions:

First, religion should stay clear of money matters and should be solely concerned with the spiritual welfare of its members.

Second, the Church already possesses a fortune evidenced by the size of the church and its many facilities. Somehow, the church has stashed away in some secret corner, a magical goose that can endlessly lay golden eggs.

Third, Jesus shows us a perfect example of how we Christians should abhor the commercialising of religion by His action of turning out all the merchants and traders from the Temple precinct and then accuses them of turning His Father’s house into a market.

Our gospel story is often interpreted as testimony against materialism in religious practice. Religion is to remain radically pure in regard to the corruptions of commerce. Christianity is solely about faith. Money plays no role whatsoever. So, was our Lord’s action in today’s gospel passage a call to keep things simple and cheap, that the Church should avoid any effort to raise funds for its maintenance and activities? You will be surprised with the answer.

In case you may have noticed, the Gospel of John states that Jesus cleansed the temple early in His ministry, but the other gospels place the temple-cleansing near the end of His ministry. Only in John’s gospel do we have the Jews confront our Lord with this question: “What sign can you show us to justify what you have done?” And it is this question which opens the discussion on the significance of our Lord’s action in pointing to His own death and resurrection.

The Temple was the focal point of every aspect of Jewish life and identity. From a theological and liturgical perspective, for a first-century Jew, the Temple was at least four things: (1) the dwelling-place of God on earth; (2) a microcosm of heaven and earth; (3) the sole place of sacrificial worship; (4) and where there is ritual sacrifice, you would also need the priesthood. Therefore, sacrifices offered to God could only be made at the Temple and never elsewhere. This is also the reason why there were traders selling animals in the Temple because these animals were meant for the Temple rituals, offering and sacrifices. The moneychangers also served a similar role of exchanging the profane Roman currency, which was considered idolatrous and unclean with Temple coinage, the only currency accepted in the Temple.

But the temple was also a barometer of sorts for the health of the covenantal relationship between God and the people. Many of the prophets warned that a failure to uphold the Law and live the covenant would result in the destruction of the temple. In 587 B.C., the temple was destroyed by King Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonians, marking the start of The Exile. Following the exile, the temple was rebuilt, then damaged, and rebuilt again. But even this second temple would be destroyed by the Romans in 70 AD. Was it in this context that we can understand the words of our Lord, “Destroy this sanctuary, and in three days I will raise it up”? St John gives us the answer: “But He was speaking of the sanctuary that was His body, and when Jesus rose from the dead, His disciples remembered that He had said this …”

Our Lord Jesus saw that all four aspects of the Temple were being fulfilled in Himself and in the community of His disciples. (1) His body is the dwelling place of God on earth - the meeting place between heaven and earth; (2) He is the foundation stone that would be the beginning of a new Temple and a new creation - the new heaven and earth; (3) He would offer Himself as the perfect sacrifice that will accomplish what previous animal blood sacrifices were unable to achieve - atonement for sin and communion with God; (4) and finally, Jesus is the High Priest of the new eschatological priesthood that could serve as the perfect mediator between God and man. Because of this, the old temple was destined to pass away, to be replaced by the new Temple “not made with human hands,” and the old priesthood with the new.

Was Jesus, in cleansing the temple, attacking the temple itself, and by extension, an attack on God as well? No. And did Jesus, in making His remark, say He would destroy the temple? No. But, paradoxically, the love of the Son for His Father and His Father’s house did point toward the demise of the temple. “This is a prophecy of the Cross,” wrote Joseph Ratzinger, who later became Pope Benedict XVI, “He shows that the destruction of His earthly body will be at the same time the end of the Temple.”

So, the new and everlasting Temple was established by the death and resurrection of the Son of God. Through our Lord’s death and resurrection, the place for encountering God will no longer be the temple but the risen and glorified Body of Jesus in the sacrament of the Holy Eucharist, where all mankind is united. With His Resurrection the new Temple will begin: the living body of Jesus Christ, which will now stand in the sight of God and be the place of all worship. Into this Body He incorporates men. This is what the Catechism tells us: “Christ is the true temple of God, ‘the place where his glory dwells’; by the grace of God, Christians also become temples of the Holy Spirit, living stones out of which the Church is built” (CCC 1197). Through baptism we become joined to the one Body of Christ, and that Body, the Church, is the “one temple of the Holy Spirit” (CCC, 776).

Finally, this story of the cleansing of the Temple also points to an important aspect of our spiritual lives, an element so relevant during this season of Lent - spiritual purification. Christ has come not only to “cleanse the Temple of Jerusalem,” but the temple of our own bodies, our lives. Our Lord’s purification of the Temple reminds us today of the need to purify our faith, to once again ground our lives on the God who shows us His power and infinite love on the Cross, the source of our salvation. Only by passing through the Cross will we reach the glory and joy of the Resurrection. The Lord Jesus comes into your life expecting to find a place ordered to the worship of the one true God, but what He finds is “a marketplace,” a heart that is divided by competing values and allegiances. Instead of a heart that is solely dedicated to God, Christ finds a place where things other than God have become primary. What rivals to the one true God have you allowed to invade the sacred space of your soul? Entertainment, leisure, material wealth, obsessions and addictions? How are these things enshrined in the sanctuary of your own heart leaving no room for God? During this Lent, let us reorientate our lives, consecrate our hearts solely to God and rid the temple of our own bodies of the idols to which we have foolishly given power and pride of place.

Thursday, April 20, 2023

The Road which leads to the Eucharist

Today’s gospel reading is a bit of an anomaly, a departure from what we would have expected. In Cycle A of the lectionary, the gospel selections are normally taken from the Gospel of St Matthew and in the season of Lent and Easter, we are also treated to passages from the Fourth Gospel, that of St John’s. But today, we are given this famous passage taken from the Gospel of St Luke. It’s the story of the two disciples on the road to Emmaus. Their faith had died along with the man whom they had trusted and followed. At the beginning of the story, the two are weighed down by the heavy spectre of death, like an albatross hung around their necks … the power of the resurrection had yet to touch them.

This story, therefore, connects our Lord’s story with ours. His resurrection is not just a one-off event exclusively experienced by Him alone. The resurrection is often viewed primarily as the awesome miracle that validates the teachings of Christ and vindicates Him against His accusers. But it is more than such crowning evidence – much more. Through faith, His resurrection can become ours - and we see this amazing phenomena in the story of the road to Emmaus.

These two disciples, like so many of Jesus’ followers, were trying to make sense of their pain and loss. Their walk to Emmaus must have felt like a walk in the desert, in the darkness of death, where hope had been abandoned. The reason why this story resonates with so many of us is because we have been there in that dark place, walking, trudging along as we drag our feet through the valley of death and tears. That is the condition of humankind unable to find hope when they have not encountered the Risen Christ. There is no need for me to remind you that life is full of contradictions, pain, and a lack of answers. There is unimaginable darkness in this world, and we often seem to have to face it alone.

The death of Jesus on the cross was the epitome of all the contradictions and evil, for if there was going to be a solution and an end to our despair, it would be in the hands of the Saviour that God had sent to us. But as far as the disciples are concerned, He is dead. If our Saviour is dead, then there is no hope.

And so on this path of darkness, our Lord appears to them and accompanies them. He recounts the whole story again, but this time invites them to enter into that story and walk with Him, as He walks along with them. He helps them see that the entire fabric of scripture is focused on Him, finds fulfillment in Him and can only be understood in Him. Here we see the amazing Spirit inspired gift of story-telling – a story of contrast – as these disciples walk home, the evening draws near and it gets darker. But in terms of their faith, as the Lord begins to expound on the scriptures and open their minds to the secrets therein, their faith becomes brighter.

But the moment of recognition will not come at the end of this long biblical exposition. It must have been an exceedingly long sermon because it would have been preached from morning till late evening. Most of you would not have been able to sit quietly through a 10 minute homily by the priest each Sunday - perhaps the solution is not found in making the homily shorter, but longer! The Word of God must ultimately lead to the Sacrament. It is in the Eucharist that the Word becomes flesh. And so, St Luke is using the very same words which he had used in Chapter 22 to describe the Eucharistic meal. At the table, He took the bread, and blessed and broke it, and gave it to them.

It is in the communion of the Body and Blood of Christ that He gives Himself fully to them. It is in the communion of this broken Body, that they can truly meet the Risen Christ. The opening of the Scriptures was necessary, but it was not sufficient. The Word must lead to the Sacrament because we can only find the Risen Lord fully and be in full communion with Him in the meal of the kingdom, the bread of life, the manna from heaven, the medicine of immortality. The Word of God did not become a book of dead words. The Word became flesh, dwelt among us and now feeds us with His flesh and blood in the Eucharist. By faith, we eat and drink Christ so that eternal life is given to us.

It is here in the Eucharist that we find comfort and renewal from the despair of death, darkness and hopelessness – because in the Mass we are taken to heaven and heaven is brought to us. Heaven and earth meet together in the very Body and Blood of our Risen Lord. If we fully grasp this truth, we can then understand the great tragedy of many Catholics who have chosen not to return to church or who consistently miss Masses on Sundays. They are not just denied the sustenance of a sacred meal. In fact, they deny themselves the only food that can bring them to heaven. Here and at every Mass, we find light in darkness, life in the midst of death, victory in the brokenness, and the sure hope of our resurrection, because we have partaken in the very flesh of the One who was put to death but now, is alive again. May we always recognise Him in the breaking of bread and the sharing of His Body and Blood.

Tuesday, February 14, 2023

Never settle for less

Today, many well intentioned Catholics and even leaders would opined that the traditional path to sanctity, to become a saint, is too demanding and may even be toxic by today’s standards. We often hear this complaint that the Church and her teachings are demanding the humanly impossible from her flock; that she shouldn’t “push so hard” or people will break and leave. And so instead of demanding excellence, we settle for mediocrity. Instead of pushing up the standards with the sky (or heaven) being the limit, we demand that the Church lowers the bar to accommodate all and sundry, even those who do not make the most basic and fundamental mark - for example observing the five precepts of the Church. When communion is guaranteed despite whether one is properly disposed or not or living in sin, when sacraments are dispensed like freebies at the supermarket, thrown in as consumer’s bait, when moral and liturgical laws are flagrantly violated in the name of pastoral inclusivity, you know you’ve hit rock bottom, or perhaps worst - we’ve bottomed out.

Today, we see the rise of mediocrity in every sphere. In fact, many celebrate their mediocrity by announcing, “this is who I am, take it or leave it!” When mediocrity has become the norm, when our imperfections and limitations are applauded or even hung up like trophies, when the status quo is accepted without question, there is no longer any impetus to improve ourselves, to grow or advance in sanctity. Mediocrity today poses as democratisation, inclusiveness, populism, condescension, tolerance, broad-mindedness, optimism and even charity. Mediocrity provides the anaesthesia our society needs to shield it from the sting of suffering and sacrifice.

In other words, mediocrity presents the promise of salvation without a cross, charity without needing to sacrifice. We try to make religion easier and more accessible in order to stem the steady decline in followers. But mediocrity is settling for cheap; it is selling a lie, and eventually most people will catch on to a lie, which explains why we continue to haemorrhage numbers. Easy come easy go!

The call to holiness, ultimately, is a call to perfection. Being average or just good when it comes to holiness just doesn’t make it! As Christians, we hear Christ’s rallying cry to walk the extra mile, to go out into the deep end, to make the greater sacrifice for faith. We are all called to be saints! You will hear Jesus constantly prodding you, “Why do less when you can do more?” He came to raise the bar, not lower it. “Be perfect as your Heavenly Father is perfect.”

The truth that we must embrace is that religion is supposed to be hard, like anything else worth doing particularly since it concerns eternal life. The way forward is up, not downwards. We should reach for the stars instead of being contented with mere pebbles of star dust. To a secular mind, saints are shockingly unreasonable. But can one love God too much? Can one be too humble or too charitable or too holy? Scriptures tells us that this can never be. Even our Lord Himself would demand nothing less than perfection: “You must therefore be perfect just as your heavenly Father is perfect.” And no good Christian can ever accuse our Lord of being too extreme or unreasonable.

What our Lord is proposing to us today is that we Christians should never just settle for being good or be contented with just being average. The call to perfection is the challenge that Christ throws to everyone who would follow Him, that is to reach the unreachable; to leap beyond the practical, the ordinary and the routine; to fulfil the basic and minimum requirements and then to look eagerly for more ways to give, care, and love. That is why devotion to the saints is such a necessary antidote to the poison of mediocrity in modern times. The saints remind us that perfection in terms of holiness is possible and attainable, even though it may take a lifetime of surrendering to God’s grace as we progress in discipleship. We are made to be saints, being “half-baked” just doesn’t cut it. To quote one of Pope Francis’ favourite theologians, León Bloy, when all is said and done, “the only great tragedy in life, is not to become a saint.”

My dear brothers and sisters in Christ, you are meant to live a heroic faith, not a mediocre forgettable one. You are meant to shine like stars in the heavens, not just appear to be a shiny bling on some counterfeit Versace outfit. If you feel that this is overwhelming and you don’t have what it takes to be a saint, know this: It doesn’t take your strength but your surrender. It will cost you everything but gain you so much more. There is a life you’re meant to live, and Christ can help you get there. Make it your aim to live higher in your faith each day, instead of dragging your feet in the mud of mediocrity. In whatever you’re going through, it is meant to take you higher. The Apostle James assured us that “when troubles of any kind come your way, consider it an opportunity for great joy. For you know that when your faith is tested, your endurance has a chance to grow. So let it grow, for when your endurance is fully developed, you will be perfect and complete, needing nothing” (James 1:2-4)

Wednesday, January 11, 2023

Behold the Lamb of God

Last Monday, we celebrated the Feast of the Baptism of the Lord. Today, we seem to encounter a déjà vu moment. Unlike the synoptic gospels, the Fourth Gospel only has this second hand reported account of the Baptism of the Lord. Being a reported account rather than a direct record of the incident by the evangelist does not diminish its value. In fact, there is added value in the testimony of an eye witness, no less than St John the Baptist. This is no mere clinical and factual account of what others would have witnessed but also provides us with John’s own mystical insight of this event.

St John the Baptist sees our Lord approaching him and cries out in an imperative almost commanding voice addressing the crowd: “Look!” John did not use the rather tepid words “this is”. Rather the original Greek is ‘ide,’ which is an exclamation, and is matched well in formal English by “behold!” It’s the kind of expression when an artist unveils his masterpiece. The invitation to ‘behold’ helps us then to better visualise what John the Baptist is doing – he spots his cousin Jesus, points a finger in His direction and in a loud thundering voice exclaims, “Behold the Lamb of God! Behold him who takes away the sins of the world!”

The next day, John is standing with two disciples. Again, he sees Jesus coming towards them, and for the sake of his disciples he repeats the words, ‘Behold the Lamb of God’. This time these words are directed to his own disciples, not the crowd in general. The Baptist acts as a kind of sign-post – testifying to the One who is greater than he. John points away from himself to Jesus. It is clear that John intended his own disciples to leave him and join Jesus. They were now expected to give their undivided attention to Jesus, the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world. John understands that his own ministry is ending – it will end. The time has come for them to follow the Messiah.

What does John expect his disciples and all of us to behold? What did he mean when he conferred on Jesus the beautiful title of the ‘Lamb of God’?

First, the “Lamb of God” is not a phrase from the scriptures that is traditionally associated with the Messiah. There is one verse in Isaiah (53:7) where the “Suffering Servant” is described as “a lamb that is led to slaughter”. For the Jews, the image of a lamb resonates with them as they remember the sin atoning sacrifices offered at the Temple. Forgiveness of sins and worship in general was a messy and bloody affair. Thank God, we Catholics have the confessional and the Mass. But for the Jews, no blood no gain. Unblemished lambs were sacrificed every morning and evening in the Temple as a sin offering, and also at the great annual festival of Passover to mark the great event of Israel’s liberation. John’s gospel supports this motif by stating that Jesus was slain at the very time that the Passover lambs were being killed in the Temple.

But then, John does not stop with the title ‘Lamb of God’, but introduces a further imagery – this is the Lamb of God “who takes away the sin of the world.” This seems to recall the scapegoat, over whose head the Jewish High Priest confessed the sins of the people on the Day of Atonement. The goat was then driven away into the wilderness, as a sign that God in His mercy had removed far away the sins of the people. So added to the Passover themes of deliverance and rescue, of freedom from slavery, is the theme of atonement for our sins.

The words of John the Baptist finds a parallel, a sort of parody, at the end of the gospel of John. Pontius Pilate presents Him, flogged, bloodied, crown with thorns before an angry mob crying out for His execution. Pontius Pilate announces to them, “Ecce Homo” (Latin), “Behold the Man”. This disfigured person seems too human, in comparison to the idealised image of the Messiah they were expecting – a man of skin, blood and bones. “Behold the man!” Pilate didn’t know what he was saying, but John the apostle did. Jesus is the perfect man. The image of the invisible God, the beginning and the end, the One in whom all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell. The One who shows us what God always intended humanity to be like. He is the One who takes the shame of our sin and bears the mockery of evil. The masterpiece of God’s creative work. When, therefore, Pilate sarcastically introduced Jesus with: “Behold, the man!” he said far more than he knew. “Behold, the man!” — indeed! We see before us not just a Man, we see before us the Invisible God made visible!

But it is in the Book of the Apocalypse, where we will see a convergence of these two images - Jesus identified as the Lamb of God at the beginning of the gospel of St John and Jesus as the Man of Sorrows at its end. It is the scene where St John describes his vision: “Then I saw, in the middle of the throne with its four living creatures and the circle of the elders, a Lamb standing that seemed to have been sacrificed; it had seven horns, and it had seven eyes, which are the seven Spirits that God has sent out over the whole world.” (Apoc 5:6) Jesus is the Lamb “standing” or “resurrected,” who had willingly allowed Himself to be “sacrificed” on the cross! The Book of the Apocalypse points back to the scene of the crucifixion on Golgotha and we now fully understand what the Baptist and Pilate could only perceive incompletely: the One on the cross is “the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.” “Behold!”

One of the great challenges of our time and even for the first disciples of Jesus, was making sense of Him being crucified. If He truly was the Son of God why did He suffer and die? Even the resurrection does not stifle this questioning, that Jesus rose from the dead does not make His suffering and dying any less real and problematic. But the answer to this problem at the end of the story, is found at its very beginning. It was the same two disciples who had followed John the Baptist who remembered his cryptic words “Behold, the Lamb of God!” and made the connexion between the innocent Jesus and the lamb of the Passover; linking His passing with the events of Exodus. The first disciples of Jesus preached His death not as a defeat, but as a sacrifice that takes away the sins of the world. Their ideas crystallised around the phrase “Lamb of God” and from being something shameful, the cross became their boast, from being a symbol of defeat, the cross has become a symbol of victory. His death was necessary in exchange for our lives.

That is why Christian liturgy and art show just how powerful the image of Christ as “the Lamb of God” is for Christians. Our Eucharistic liturgy still echoes the prophetic words of John the Baptist; the host is elevated and the priest says “Behold, the Lamb of God” – we are to look and recognise the innocent victim whose death takes our sins away. We recall Christ’s sacrifice as the Lamb of God, we recognise that in communion we taste forgiveness and life, liberation and salvation, the fruits and benefits of His passion. We behold Christ, in whom God has taken human flesh, and in seeing – beholding – Christ, we behold God. This is not just a man who has made Himself to be the Son of God. That was Pilate’s mistake. The Baptist understood and wanted his disciples to see what he saw. This is the Son of God who has made Himself the Man, the Lamb sacrificed and slain and left for dead but now standing erect because He is risen! Behold! Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world

Wednesday, December 14, 2022

God is with us

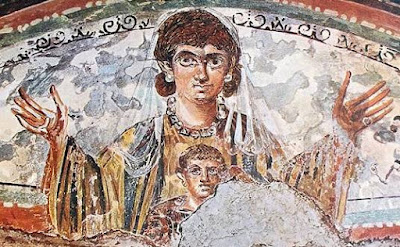

If you’ve ever had the opportunity to walk into an Orthodox Church, your senses will be immediately assaulted by a delightful riot of colours - colourful icons lining the walls, and with the largest concentration of them on the iconostasis, the icon laced screen which separates the nave of the church from the sanctuary where the holy mysteries are celebrated. But one icon stands out and provides an easy point of focus to any visitor because it is usually present in the upper part of the altar, the apsidal vault, the focal point of any church. What does this image show, and what is behind its name?

The icon shows the Mother of God from the waist up, facing us, with her hands lifted up to the level of her head, elbows bent. From time immemorial this gesture has signified a prayerful appeal to God, and still are sometimes, called Oranta (Latin for praying). The Christ-child, Emmanuel, is depicted in a circle of light at her bosom. It almost has a fish bowl effect which allows us to peer into the womb of the Blessed Virgin. But instead of a not fully formed foetus, we are presented with a miniature version of an adult Christ (minus the facial hair) with His hands extended in benediction. Although first timers would conclude that this is an icon of the Holy Mother of God, a more reflective scrutiny gives the impression of Mary presenting us with Christ, and our attention is drawn – as always with icons of the Theotokos – to her Son, our Saviour. Mary is merely the frame, Christ her son is the masterpiece.

Though it has several names, the most common name for this icon is the Lady of the Sign. It derives its name from this passage which we just heard in the first reading: ‘The Lord himself, therefore, will give you a sign. It is this: the maiden is with child and will soon give birth to a son whom she will call Immanuel, a name which means “God-is-with-us.”’

This sign was a kind of a super bonus which God decided to give to Ahaz, even though the latter chose not to ask for it. For those who know the back story of Ahaz, this sudden refusal to ask God for a sign did not come from a good place, as if Ahaz did it out of humble obedience to God. In fact, Ahaz is considered to be one of the worst kings of Judah, and his own personal faults were compounded by an equally evil wife, Jezebel. Together, they epitomised the couple from hell. So, why would God “reward” this evil king with this promise of a sign?

Ahaz was about to be forced into an alliance, in a vain attempt to oppose the crushing military power of Babylon. For you Black Panther fans out there, think of this as something similar to the proposed alliance between Wakanda and Talokan - a marriage doomed for failure. The prophet Isaiah goes to Ahaz and warns him that the alliance would be fatal: he had better trust in the Lord rather than in human machinations. Isaiah promises a sign, which Ahaz refuses, not because he has a change of heart and does not want to put God to the test. The real reason for the refusal is simple - he does not want to be convinced! He doesn’t want to change his mind. But God will have none of this. Ahaz will get a sign, even if he chooses to reject it, because the sign will have a significance far greater than this political conundrum which Ahaz is facing. It would be a sign which will herald salvation, not just for Ahaz or for this moment but for all generations to come.

What is this sign? The original Hebrew simply reads, ‘A girl is with child and will bear a son’, indicating that within a few months the threat will vanish and Jerusalem will be convinced that God is on their side – hence the boy will be called Emmanuel, “God-is-with-us.”. But the Greek translation of the Hebrew, made some 200 years before the birth of Jesus, translates ‘The virgin (or maiden) is with child’, which the evangelist Matthew sees as a prophecy of the birth of Jesus from the Virgin Mary.

In the gospel, we have another man who is promised a sign but this man is the diametrical moral opposite of Ahaz in the Old Testament. Though he is a descendant of Ahaz and King David, St Joseph is described as a “man of honour,” or in some translations a “righteous man”. Unlike, his notorious ancestor, Joseph puts up no resistance to the angel’s message through the medium of a dream: ‘Joseph son of David, do not be afraid to take Mary home as your wife, because she has conceived what is in her by the Holy Spirit. She will give birth to a son and you must name him Jesus, because he is the one who is to save his people from their sins.’ And St Matthew then adds the additional editorial note that this was to fulfil Isaiah’s prophecy: ‘The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son and they will call him Emmanuel.’

Although the prophecy says that “they will call him Emmanuel,” Mary and Joseph didn’t give their son that name. Instead, they followed the directions given specifically to them to name Him Jesus. As seen in today’s passage, the meaning of Emmanuel is ‘God-is-with-us.’ The promised child was given the name of Jesus, which means ‘God-saves.’ There is no contradiction between the two. God is with us not in some dormant or passive way. He is with us for one singular purpose - to save us.

So, today, even if you are not ready for a sign or feel any need for a sign, even if you have not asked for one, know this, that God will give you a sign; indeed, He has given you one, the only one that truly matters - His Son Jesus Christ, our Lord and Saviour. If you’ve ever asked for a sign from God, especially when you are at the crossroads and at a moment of decision, know this to be true - God has given you the sign: “The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son and they will call him Emmanuel.”

Think about it. Isn’t this the sign you’ve always craved? Haven’t your hearts been asking for nothing less than this – that God should know what it’s like to be you, to understand your deepest pain, your hardship, and your daily struggles. To learn what it means to be here, to be in your shoes, to be with us. That was the promise and this is the sign. God would come. And soon, very soon, we will celebrate His virgin birth. He came here to die. He came to free us from this world of sin. He came not just to be with us, but to make it so that we could forever be with Him. With Christians throughout the world and through the centuries, let us cry:

O Come O Come Emmanuel,

And ransom captive Israel

That mourns in lonely exile here,

Until the Son of God appear.

Rejoice! Rejoice! Emmanuel

Shall come to thee, O Israel.

Wednesday, May 25, 2022

Be His faithful witnesses

Solemnity of the Ascension of the Lord

It is significant that St Luke tells the story of the Ascension twice, and we have the benefit of hearing both accounts today – the account from the Acts of the Apostles in the first reading, and a second account in the Gospel. Each narration brings out a different aspect of the truth but the theme of witnessing seems to bind both Lucan accounts. For St Luke, the Ascension was a significant moment in the disciples’ personal transformation. It marked a critical turning point, the passing of the Lord’s message and mission to His disciples.

In the Acts account, just before He ascends, the Lord promises His Apostles, “you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you, and then you will be my witnesses not only in Jerusalem but throughout Judaea and Samaria, and indeed to the ends of the earth.” Similarly in the Gospel, having reiterated the kerygma, the kernel of the Christian faith, that “Christ would suffer and on the third day rise from the dead,” the Lord gives them this commission: “In His name repentance for the forgiveness of sins would be preached to all the nations, beginning from Jerusalem. You are witnesses to this.” In other words, when Christ ascended, He left with the intention that the Church takes up where He left off.

The Acts version of the event also paints a rather comical scene. The disciples are standing there, first looking at the Lord ascending and then, they continue staring at the clouds. They are then shaken out of their stupor by the question posed by two men in white, presumably angels: “Why are you men from Galilee standing here looking into the sky?” The question could be paraphrased, “Do you not have something better to do than to stand here and gawk?”

Here lies one of the greatest challenges to Catholics – our inertia to engage in mission. We seem to be transfixed firmly in our churches but feel no need or urgency to reach out. We Catholics have been “indoctrinated” to attend mass every Sunday and on holy days of obligation. The Liturgy is supposed to be the “source and summit of the Christian life.” So, we should see it not just as an end but also as a starting point for mission. Yes, worship is our primary activity, as witnessed by the Apostles at the end of today’s Gospel. But what about mission? It is a false dichotomy to pit worship against mission. It’s never a hard choice between the two. Both worship and mission are part of the life of a Christian. They feed off each other.

The Ascension reminds us that the Church is an institution defined by mission. Today all institutions have a statement of mission; but to say the Church is defined by mission is to say something more. The Church is not an institution with a mission, but a mission with an institution. As Pope Francis is fond of reminding us - the church exists for mission. To be sent, is the church's raison d'être, so when it ceases to be sent, it ceases to be the Church. When the Church is removed from its mission, she ends up becoming a fortress or a museum. She keeps things safe and predictable and there is a need for this – we need to be protected from the dangers of the world and from sin. But if her role is merely “protective” she leaves many within her fold feeling stranded in a no man's land, between an institution that seems out of touch and a complex world they feel called to understand and influence.

On the other hand, the Church cannot only be defined by her mission alone, but also by her call to worship the One who has sent her on this mission. If this was not the case, she would be no better than a NGO. But the Church of the Ascension is simultaneously drawn upward in worship, and pushed outward in mission. These are not opposing movements and the Ascension forbids such a dichotomy. The Church does not have to choose whether it will be defined by the depth of its liturgy or prayer life, or its faithfulness and fervour in mission. Both acts flow from the single reality of the Ascension. Both have integrity only in that they are connected to one another.

At the end of every mass, the priest dismisses the faithful with one of these formulas, “Go forth, the Mass is ended!” “Go and announce the Gospel of the Lord!” etc. Mission is at the core of each of these formulas. The Sacrifice of the Mass is directed and geared towards this purpose – the continuation of the mission of Christ. The Eucharistic Lord invites us, He commands us, to share in His mission, and to preach the Gospel everywhere.

If worship is the beginning of mission, then mission too must find its ultimate conclusion in worship – for the liturgy is the “source and summit of the Christian life” as taught by the Second Vatican Council. Worship must be at the heart and the soul of mission. This is beautifully depicted in the Novgorod School’s icon of the Ascension. The apostles are excited and ready to carry out the mission entrusted to them by the two angels at the scene of the Ascension. And yet, the Blessed Virgin Mother stands serenely in the middle of this icon, with her hands raised in the traditional gesture of prayer (orans). She seems to be the sturdy anchor that holds them rooted to the Ascension event, reminding them that their mission must always be anchored in Christ through prayer. So, the more authentically missionary a church becomes, the more profound will be its life of worship, since mission always ends in worship.

Those first Apostles took seriously our Lord’s command that they preach the Gospel to all nations, and the fact that we are Christians here today centuries later and thousands of miles away from the birth of Christianity, is positive proof of how seriously they heeded His command. From its very origins, then, the Church has had an outward missionary thrust. The work Christ began here on earth, He has now entrusted to us so that we may continue. If we have truly caught on to the message of the risen and ascended Christ, we should not just stand here looking up into the skies, waiting for an answer. We are called to get going and do the job our Lord has given us to do, never forgetting that we must remain connected to Him through our worship and prayer. With the help of the promised Holy Spirit, you will be His faithful witnesses “not only in Jerusalem but throughout Judaea and Samaria, and indeed to the ends of the earth.”

Thursday, November 26, 2020

Wait, Watch, Witness

First Sunday of Advent Year B

For the past few months, we have been constantly reminded by the public health authorities to practice three actions which should form the basis of a “new normal.” To help us remember they adopted a simple mnemonic: 3 W’s- Wear a mask, Wash your hands, Watch your distance.

Today, the readings also present us with a

simple 3 action formula, not just for this season of Advent but for the entire

season of our lives as we await the Advent of our Lord at the end of this age.

Taking the cue from public health mnemonics, let’s consider them under our own

set of 3 W’s: Wait, Watch and Witness.

Waiting is one of the principal movements

of Advent. At every Mass, after praying the Lord’s Prayer, we hear “. . . as we

await the blessed hope and the coming of our Saviour, Jesus Christ.” This

prayer reminds us that during Advent, we wait in joy, in hope, and in

anticipation for the wonderful event we are about to experience—the feast of

Christmas, the coming of Christ into our lives in new ways, but also the return

of Christ in glory at the end of time.

Isn’t it amazing that the Church has an

entire season dedicated to fostering the virtue of waiting because she

understands its essential value in our lives. Fasting is the necessary prelude

to feasting; excellence is contingent on the readiness to sacrifice; enduring

joy can only emerge after passing through the crucible of aches, trials and

sometimes, great suffering. There are multiple examples taken from nature to

back up this proposition. A tree does not just spring into existence without having

to pass through various stages of growth, from seed to sapling, from the first

leaf to sprouting branches, and finally producing its first flower from which

the first fruit would emerge. Everything of value takes time and when it

finally bears fruit, there is a realisation that it was worth the waiting.

Unfortunately, waiting is not popular in today’s society which is driven by an

obsessive attitude of instant-gratification. In an “instant” culture, waiting

can seem unbearable, almost “hellish”. Waiting, therefore, requires a maturity

that many of us do not possess. Children want instant gratification. Adults

should learn to wait.

The Church’s liturgy helps us to

understand that there is a sacred dimension to waiting. In Advent, the Church

takes on a very counter-cultural stance. We don’t turn our days of waiting

prematurely into the commercial Christmas that surrounds us. We take seriously

the importance of learning the art of waiting in joyful hope, prayer and spiritual

preparation. This waiting is far from empty. It fosters self-denial, a spirit

of sacrifice, repentance, prayer and learning to trust in God’s providence. In

this time of pandemic, Advent is the perfect season to assuage our fears and

impatience. It teaches us to wait upon the Lord, for as the prophet Isaiah

assures us “those who hope (wait upon) the Lord will regain their strength…”

(Isaiah 40:31).

Advent is also a season of watching. In

the gospel, our Lord calls us to sober watchfulness: “Be on your guard, stay

awake.” This is what we hear in the First Advent Preface: “Now we watch for the

day, hoping that the salvation promised us will be ours, when Christ our Lord

will come again in his glory.” Watching is not just a major theme for Advent

but also a major theme in scriptures. Our Lord frequently warns us to be alert

and to watch, because we do not know when He will return. There is a double

sense of His coming. At some unknown time, perhaps soon, He will return and we

must be alert and watchful, our lamps burning, ready to give an account. But even

more urgent is the fact that probably much sooner, He will call each of us to

Himself as we pass over into eternity. We are then, in the words of Paul, to

avoid the works of darkness and to watch and be sober (see 1 Thess 5:6 and Rom

13:11-14).

We watch for we know not the day and the

hour of the Lord’s coming. We watch because we must be constantly on guard

against temptation and sin. We watch in prayer, because prayer is the only

antidote and defence we have against the power of Satan. To watch means to

enter into the mystery of Christ’s passion and death. Notice that in the

parable of our Lord, four specific times are mentioned: “evening, midnight,

cockcrow and dawn.” These are the names used for the four “watches” between 6

pm and 6 am. Although, the Hebrew tradition counted three watches, the Romans

divided their night into four segments. Interestingly, these four hours also

correspond to the four hours of our Lord’s Passion, the evening of the Last

Supper, the midnight at the Garden of Gethsemane, the cockcrow at the moment of

Peter’s denial and the dawn of His trial and subsequently His resurrection. It

is as if we are plunged into a long night that only breaks into dawn on Easter

morning. We would have missed the most important event in human history and the

climax of salvation history, if we fail to be watchful.

This leads us to the third thing we must

do – we are called to give witness. St Paul commends the Corinthians in the

second reading because they were filled with enthusiasm, richly endowed with

the Holy Spirit and “the witness to Christ has indeed been strong among” them

as they awaited the return of the Lord. Advent may be a season of waiting but

not idle waiting. Advent should always be an opportunity to shape our faith,

inculcate patience in waiting, and sharpen our vigilance. It is anything but a

season of stagnation and passivity. On the contrary, Advent is a season where

Christians must go to work and much work has to be done before Christ returns. We recall the parable of the talents where we

are invited to imitate the example of the first two industrious servants and

avoid the folly of the third servant who was idle. Likewise, Christians must

take this opportunity between our Lord’s first coming and His second coming, to

witness to God’s mercy and grace, and be committed to working for the salvation

of souls.

The message of Advent challenges our

impatience, and heals our frustration and anxiety. We’re called to wait with

greater calmness, to watch with greater vigilance, to witness with greater

resolve, and finally, to live with greater hope. So, we wait not like a lost

ship at sea seeking a distant port, but as God’s people already comforted by

the knowledge that we have a permanent and eternal home. We wait with not so

much idly for a “second coming,” but for signs of the Risen Lord who is already

in our midst and who calls us to cooperate in completing His work of salvation:

“Wait with Hope! Watch with Vigilance! Witness with Courage!”