Monday, July 22, 2024

When Little becomes Abundant

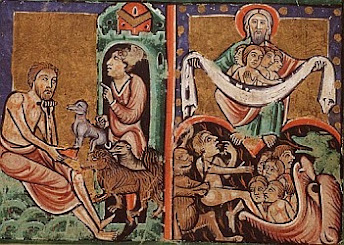

There is this wonderful line which could only emerge from the inspired genius mind of St Augustine: “The New Testament lies hidden in the Old and the Old Testament is unveiled in the New.” This is what we see in our lectionary’s juxtaposition of the first reading and the gospel. Both readings provide us with two incidences of miraculous multiplication of bread, the first implicit, while the latter clearly more explicit by virtue of its scale. Elisha multiplied 20 barley loaves so as to feed 100, with some even left over. But in the Gospel, our Lord multiplies 5 barley loaves and feeds 5,000, leaving 12 baskets left over. We’re talking serious one-upmanship here!

What does the multiplication story of Elisha in the first reading and our Lord Jesus have in common is their seven-part movement in the narrative: a crisis arises due to shortage of food, a chanced character volunteers to make an offering of meagre means, the protagonists issue a command to feed the crowds with these limited resources, followed by incredulity, a second command is given, the feeding takes place and finally, there is food left over. Both narratives fit nicely into this 7-part template. But there is no equivalence. What our Lord does, out matches what is done by Elisha and in fact by Moses who fed the Israelites with manna from heaven. This is no mere coincidence.

Christ brings to complete perfection what had already been prefigured in the Old Testament. That is why we should not easily dismiss the Old Testament as historically obsolete or mythical stories. To know Christ in the fullest sense (sensus plenior), then, we must read not only the New Testament, but also the Old. Our Lord Jesus is not just another great prophet in a long line of prophets but He is of an entirely different category which surpasses all that has preceded Him. If the prophets of old had only communicated the Word of God as mediums of transmission, Jesus is the Word of God in the flesh.

Both stories begin in a context of hunger. Few understand the depths of hunger. Becoming hungry for most of us is a matter of choice. Fasting and dieting are deliberate choices. But one must also consider the hunger of millions of people in the world: “the siege of the poor”. They have no choice but to be hungry.

But it is the hunger of such as these that reminds us that life begins with hunger and to be alive is to be hungry. The dead do not experience hunger pangs any longer. Some people are so hungry that for them God cannot but have the form of a loaf of bread. It is no wonder that in both stories of multiplication, we are reminded that the paradigm which God shows us and which we must imitate is giving and not hoarding. That is why the Lord commands His disciples to count the cost of what is to be given and to make an inventory of what they possess.

The miracle of the multiplication of the loaves and the fish, therefore, shows us that the Lord is not concerned with the quantity of the bread; what He desires is that the bread be shared. The hunger of others has rights over me. It never ceases to amaze me at how much energy we put into making excuses that we don’t have enough to share with others. According to a mysterious divine rule: when “my” bread becomes “our” bread, then little becomes enough. Hunger begins when I keep my bread to myself, when I choose to hold on to my bread, my fish, my assets. In contrast to our penchant to be calculative, our Lord shows us another way of being wholly generous because we have received so much from Him. The fact that there were twelve baskets of leftover food is a reminder to us that His grace is aplenty and that it is free.

Because of this last point and for this reason, the seemingly logical explanation of this miracle being the result of the crowds sharing their personal stash of food is untenable. This is not just a story of sharing but one of revelation. Only God could complete such a feat. As God rained down manna in the desert, Elisha increased his meagre supply of bread to feed the hundreds and now our Lord multiplies the bread and fish to feed the multitude of thousands, none of these events could have happened without God’s intervention. It is simply not possible for the disciples or the people to feed themselves or each other. They could not heal themselves or each other. But God can and God does.

So, the grain of truth that confronts us in today’s readings is that we are subject to limitations. We are not able to do everything, we are not able to help everyone, we are not able to save everyone. But that does not absolve us from doing something or helping someone. When we entrust the little that we have to God, He will ensure that our efforts would not be impeded by our limitations. On the other hand, these stories remind us that for a miracle to happen, it is not about God creating something out of nothing. God takes what we offer Him and ensures that it is always enough for us to share it with others, with much more to spare.

Our financial resources, talents, and holiness are clearly inadequate to meet the needs of a hungry and confused world. But what else is new? This gospel commands us to offer these resources anyway, trusting that God will multiply them. Don’t just take my word for it. See it happen at every Mass. In the Eucharist we bring the very ordinary work of our hands, bread and wine, and join to this the offering of our very ordinary lives. Through the invocation of the Spirit and the Word of God, this offering is changed into the Body and Blood of Christ, the Bread of Life and the Cup of eternal salvation. Likewise, we offer Him the work of our hands and our broken humanity, and He transforms these things into perfect humanity and life-giving divinity. And with this He not only feeds us but empowers us to feed the whole world. When “His” bread becomes “our bread”, then little becomes abundant!

Monday, September 19, 2022

Get off your comfy couch!

Having gone back to pre-pandemic full capacity, many parishes are awkwardly still witnessing relatively low attendance at Masses. What could be the cause of this? In 2020 and 2021, as our country navigated between complete lockdowns and impossibly stringent SOPs governing public gatherings when some activities were allowed, many of our churches discontinued physical attendance at Masses for long stretches and substituted them with online services. According to the best research, it takes 60–70 days to form a new habit, and we had months of lockdowns and two years of restrictions! That’s plenty of time to form a new habit.

In today’s first reading, the prophet Amos confronts the people of Israel for their spiritual lethargy. He accused them of “lying on ivory beds and sprawling on their divans” while dining on their fatted lambs. He was practically telling them to get off their comfy couches, cease living a sedentary life seated in front of their televisions while gorging on junk food, while ignoring all the critical things happening around them. Apathy or indifference to the cries and plight of the poor, the marginalised, victims of oppression and injustice had become a new habit which they found hard to abandon.

We see a vivid illustration of this in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, in the gospel. The rich man who enjoyed life was condemned to hell at the end of the story whereas Lazarus who suffered in this life, ended up in heaven. The parable is troubling not only for its mention of hell but because the rich man should even end up in hell, though he is not depicted as a horrible person. In fact, the gospel never states that the rich man mistreated poor Lazarus. There is no mention of him acquiring his wealth through unjust means. The point of this parable is not that the rich will be damned and the poor will be saved. Neither is the point of this parable describing a capricious God who likes sending poor souls to hell for the slightest infraction. The problem with the rich man, if you could consider it a problem, is that he was without suffering - he had no inclination of suffering because he had all the luxuries which money could buy. For this reason, he couldn’t feel the pain and the suffering of the beggar Lazarus.

What did the rich man do that was so horrible that he should deserve such a terrible fate as hell? It was simply his apathy. Apathy is indifference habitualised. Examining the Greek root of the word would give us a better understanding of this sin. Apathy comes from two Greek words - “a” which denotes the absence of something, “without”; and “pathos” which means suffering. Therefore, the apathetic person is one who does not know or feel the suffering of another, as opposed to an emphatic person, someone who experiences and feels the suffering of the other.

This was the “crime” of the rich man - he was enclosed in his safe little world of personal enjoyment, insulated by his wealth and comfortable life. Lazarus, therefore, was not treated as a part of suffering humanity but just a part of the landscape. In a word, the rich man was indifferent, and clueless: Indifferent to Lazarus’ plight, indifferent to his hunger, indifferent and clueless to his needs. They were the neighbours who never met.

The indifference which blinded the rich man to the needs of Lazarus and others in this life is a foretaste of what is to come - the chasm that separates heaven from hell, a chasm wide and unbridgeable. There is no passing between the two, ever. In life, a big chasm had opened up between the rich man and Lazarus due to the former’s apathy. Lazarus never showed up on the rich man’s radar. In death, this chasm has grown infinite – in the words of Father Abraham, a ‘great gulf’ separates the minions of hell from the minions of heaven. The chasm which the rich man maintained through his indifference in life had ultimately separated him from God in death. Now, it’s the rich man’s turn to drop off God’s radar. Indifference does not only spell human tragedy, but it also means the lost of beatitude, the lost of salvation.

An apathetic person will not exert any effort to make a difference. He either sees no need to do so or feels so overwhelmed by the problem that he believes that whatever he does will make little to no dent in the issue. He tells himself, “What’s the point?” “Is this my problem?” Or “how does this even concern me?” He will simply sit back and watch events unfold. Unfortunately, this is all that is needed to make one’s journey to hell certain. In the words of the philosopher Edmund Burke, “All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.”

Apathy may seem as insignificant as a tiny crack but it eventually morphs into a great chasm that comes between heaven and hell. Apathy is what makes us ignore the message of the prophets and pass generations and even makes us turn our backs on the One who died and is now risen from the dead. In fact, apathy is what killed the Lord Jesus Christ. Both the fearful Pilate and the jealous High Priests would not have been able to put Jesus to death except for the thousands of people who didn't show up for the crucifixion. They didn't want Jesus dead or alive. They just didn't care. Apathy permitted Hitler to kill six million Jews, and abortion clinics to kill many more millions of babies. Apathy lets thousands die each day of starvation, and billions live each day without knowing Jesus.

At the end of the parable, the rich man asked Abraham to send Lazarus back to earth to warn his brothers to repent so that they would never join him in hell. Abraham told the rich man that if his brothers did not believe in Scripture, neither would they believe a messenger, even if he came straight from heaven. Looks like man’s indifference to his neighbour is finally unmasked – it is merely a cover, a symptom of man’s indifference to God.

Both Amos and our Lord are calling us to get off our comfy couches and to get going. There is no room for couch potato Christians. In fact, being Christian means that we must change our apathy into empathy, we cannot cut ourselves from others because as St Paul reminds us: “If one member suffers, all the members suffer with it.” In his personal letter to Timothy which we heard in our second reading, St Paul outlines what is required of us: “As a man dedicated to God, you must aim to be saintly and religious, filled with faith and love, patient and gentle. Fight the good fight of the faith and win for yourself the eternal life to which you were called when you made your profession and spoke up for the truth in front of many witnesses.”

Thursday, February 10, 2022

How happy are you who are poor

We are finally reaching the end of the Chinese New Year festive season with the famous Chap Goh Mei (or simply, the 15th day) celebration on Tuesday. I believe many of you have broken new records of the number of yee sang tosses for the current year, number of ang pows you’ve received and for the adults, a record deficit in your personal account. One of the festive greetings that you will hear most frequently to the point of ad nauseum, is Gong Xi Fa Chai or its many dialectical equivalents. Most non-Chinese speakers would mistake this as simply meaning “Happy New Year”, only to be surprised and shocked by its actual literal translation: “May you have increased wealth/ prosperity!” The greeting seems to reaffirm the unflattering stereotyping of the Chinese as people who are obsessed with money and wealth. Well, I can assure that for many, even the non-Chinese, happiness is often tied to how much money you possess. So, for the last time this year: “Gong Xi Fa Chai”.

A good friend of mine once asked why we Catholic priests can’t preach like famous televangelists, the likes of Joel Osteen. She was referring to the message which is commonly known as the gospel of prosperity. Joel Osteen once told Time Magazine: “I preach that anybody can improve their lives. I think God wants us to be prosperous. I think he wants us to be happy.” And so, my friend’s contention is that instead of making Catholics feel guilty for being rich, can riches be justified and even promoted in our preaching? Can this simple formula be expounded more frequently and more assertively from the pulpit: “the more you give the more you get”? Can every homily sound like a Chinese New Year greeting?

The answer which I will give is going to disappoint my friend and anyone else who would expect to hear us preach about God’s blessings in the form of wealth, good health and endless happiness. But disappointment is too mild a term. St Luke’s Gospel uses the harshest language toward the rich and also treats the poor in the most flattering way. For example, in Luke’s version of the Beatitudes which we heard today, Our Lord not only pronounces a blessing on the poor, He also pronounces curses on the rich. Instead of wishing you a prosperous life, our Lord issues this strange blessing: “How happy are you who are poor: yours is the kingdom of God.” On the other hand, He addresses the rich in this way: “But alas for you who are rich: you are having your consolation now.”

What seems most disturbing about the Lukan beatitude, especially the first, is the inexplicable canonisation of poverty and the ensuing situations which normally spell tragedy. It has none of the spiritual dimension that is found in St Matthew’s version - “poor in spirit” - a term which could equally include the rich as well as the poor, because spiritual poverty can afflict anyone regardless of their economic status.

What is it about poverty that is so “blessed” or “happy” or even authentically “human”? We must first make a critical distinction between poverty and destitution. All human beings are entitled to have their basic needs met. The fact that millions are living in our world in the state of destitution, where hunger and disease ravage entire nations, is a great sin against humanity. There is certainly no blessing in this, neither should it ever be a cause of happiness. Every time we withhold our cloak from the naked or our food from the hungry, we sin, not only against the human person, but also against the Lord Himself. But poverty, or at least evangelical poverty, is not identical with destitution. The destitute may think of themselves as forsaken, but the poor are definitely not forsaken by God. Poverty is the state of simplicity, that is the state of having only what one needs. God is the supreme wealth of the poor.

To advance in the life of virtue, poverty must come first. This is due to the chasm that lies between God and the world, the Creator and His creatures. This world and all its riches are God’s gift to us to be used as a means for our return to Him. Simply put: God is the end; things are means to this end. On the other hand, the possession of material goods beyond that of basic necessity, brings with it the risk of using goods as ends in themselves. Things therefore become our ‘idols.’ The outcome would be the proliferation of vices like greed, envy and possessiveness. It is interesting that, while Christ cured the sick, made the blind see, made the deaf hear, but He never once made a poor man rich. Illness, blindness, and deafness are deprivations; poverty is not. Likewise, when one is deprived of the basic needs of life, this physical state of destitution necessarily brings with it the challenge of spiritual destitution. This is why we must work to eliminate destitution in the world, not primarily because of the physical suffering it brings, but because we wish to allow God’s people the freedom to worship Him in health of body, mind, and soul.

Christ, in this first beatitude, does not say, “To those who are impoverished, I say to you, the day will come when I will relieve you of this poverty and make you rich.” That’s the gospel of prosperity. Instead, our Lord says, “happy are you who are poor.” Poverty itself brings with it a blessing, or rather, sanctity. The poor understand their need for God. The poor’s security and wealth lie with God. The more we possess, the further we find ourselves from pursuing our proper end: God. We cannot serve both God and mammon. The further we are from our proper end, the less human we find ourselves. This explains the unique theme of reversal, present in St Luke’s beatitudes, the so-called four ‘woes’, as opposed to the four ‘blessings’. Wealth, full stomachs, contentment and human respect, though good in themselves, can also risk becoming dangerous. They can lead us to believe only in ourselves and our resources, and forget our true end which is God and His Kingdom.

Despite what my good friend claims, the Catholic Church has not canonised material poverty as the ladder to heaven. The state of poverty cannot just be purely material; material poverty alone does not bring salvation. St Basil warns us, “for many are poor in their possessions, yet most covetous in their disposition; these poverty does not save, but their affections condemn.” Material poverty, in order to be humanising and divinising, must be accompanied by spiritual poverty – being “poor in spirit.” On the other hand, neither is the state of poverty purely spiritual. There are those who want to reduce Christ’s call to poverty, to the mere spiritual detachment from goods, and continue to live scandalously lavish lives at the expense of the poor. This too is a distortion of the Gospel message. This beatitude should certainly not excuse us from our responsibility to assist those who are in a state of destitution.

Evangelical poverty can never mean a rejection of all material goods, which are good in themselves. But it is an invitation to see that these things are better when they are shared with those who have-not. As we launch into this new year and encounter Christ in different people and situations, let us give true glory and worship to God in all that we do, in whatever we say, and in all that we possess, for He became poor so that we may become rich in His graces.

Thursday, November 4, 2021

Giving till it hurts

Thirty Second Sunday in Ordinary Time Year B

Today we are given two examples of remarkable generosity - the sort that really hurts. We have one story in the first reading where God commanded a widow to give her last bit of food to a prophet, and another story in the gospel, where Our Lord after having rebuked the teachers of the law for devouring widows’ houses, points to a widow’s giving at the Temple as exemplary. In both cases, these two women risked starvation and losing their entire livelihood in giving and sharing - one for a stranger whom she treated as an intimate neighbour and another to God.

In a way, both these women epitomise the

two-fold commandment of love which we heard last Sunday. In fact, some ancient

commentators have seen the two mites offered by the widow in the gospel as a

symbol of the two-fold Great Commandment of love.

But both these stories are not just

amazing stories meant to inspire us to be more generous and to give more, and I

can assure you that I have absolutely no issue with this message. Instead, both

stories are pointing to something greater and beyond themselves. They both

point to God’s magnanimous giving, ultimately seen in the willing sacrifice of

His Son’s life on the cross. The stories of these two widows serve as actual

living witnesses to the Lord’s death and resurrection, which is more apparent

in the first story, where we see the generous widow’s dead son being

miraculously raised to life.

The story of the widow’s mite in the

gospel could be considered from three different angles.

First, from the angle of the Temple. The

meagre contribution of this woman would have little value since those two small

coins would have made little difference to the financial upkeep of the

religious establishment. It’s the kind of loose change that one will have

little hesitation to drop in the coin box set aside for tips. The unloading of

a few extra coins would outweigh the inconvenience of keeping them. The Temple

authorities would not have missed their absence.

The second perspective would be to compare

the woman’s contribution with the other donors. St Mark tells us that other

rich people are also making offerings at this time. As their substantial

contributions are dropped into the metallic trumpet-like receptacles, it would

have been both a sight to behold, as well as produce a sound that would have

warmed the cockles of the hearts of those in charge of the Temples. They would

be thanking God for these generous donations! What would the tiny chink of the

widow’s two miserable coins matter in comparison with these generous donations.

But the last and most important

perspective of considering this story, is from the angle of Christ and God.

Those two metal flakes would have little value from the perspective of the

Temple authorities or in comparison to the other large donations, but to our

Lord, it mattered most. Because the true value of a gift depends on its cost to

the giver. Her gift may be small, but to her, it could possibly cost her her

life. That is why our Lord was quick to say, “I tell you solemnly, this poor

widow has put more in than all who have contributed to the treasury; for they

have all put in money they had over, but she from the little she had has put in

everything she possessed, all she had to live on.”

We begin to see how the generosity of this

widow in the gospel matches the generosity of the widow of Zarapeth. Both had

given up what little they “had to live on.” Their giving would have not just

have cost them their livelihood but more radically, their lives.

If this story merely focuses on the

generosity of our giving, the demands made on this poor woman would certainly

be scandalous and unjust. Aren’t we suppose to help the poor instead of

demanding such sacrifices from the poor? So, merely focusing on generous giving

cannot be the sole purpose of these stories. Our Lord is not justifying nor is

He giving approval to an exploitive system which robs the poor, the widows and

orphans. This would be the main criticism of many, who view any efforts by the

Church to do fund-raising, as a violation of the principles of social justice

and reduces the Church to a money-making enterprise. We must remember that when

the widow gives, her giving is ultimately to God Himself, who has given

everything to her. She never once complained about her gift giving but rather,

it is the rich who often use the excuse of the poor to complain about giving.

Remember Judas Iscariot, who complained about how Mary of Bethany wasted

expensive oil on the Lord.

These women never counted nor begrudged

the amount they gave because they were truly grateful for what they had

received from God. Their generous giving was merely a reflexion of their

gratitude. In this way, the widow in the gospel (just as the widow in the first

reading) is a type, who points to the extravagant giving of our Lord, He gave

up everything, including His own life, and held nothing back. Was His sacrifice

and death unjust? Most certainly by any standards. But when done willingly and

lovingly, it restored justice to our world.

The offering to the Temple will soon cease

with its destruction. But the Lord will build a new temple in His body, that

will minister to the broken, the neglected, the sinners and the poor. He will

lay down His life for this widow (and for all of us) in a way that far exceeds

her or anyone else’s faithful giving. In doing so, this widow will have a new

husband—Christ Himself—and her humble gift of two miserable coins will be

reciprocated with the greatest gift of all - the eternal life of her Divine

Spouse, who will not allow her to be exploited by those who would wish to

swallow her property because He is the One who will never leave her nor forsake

her, nor will death ever separate them.

Thursday, July 8, 2021

We are meant to soar

Fifteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Year B

A popular metaphor for describing the transition from adolescence to adulthood is that of the eagle pushing her young, forcibly and abruptly, out of the nest. The falling eaglet either has a terror-induced epiphany, “Hey, I’m an eagle, I can fly!”, or hits the ground because it believes it’s a chicken. In certain respects, this is an apt metaphor for the process of discipleship. After a period of nurturing, comes the phase of challenging and breaking new ground. For those who are willing to accept the challenge, they can soar like eagles. For those who continue to have doubts about their calling or capabilities, they will forever remain grounded like chickens.

The initial phase of training the Twelve

is complete, and they are ready to participate actively in the mission of

Christ - to become fishers of men. The first task of the apostles was “to be

with Him” (Mark 3:14), the second, is to be “sent out” (this is what the Greek

word “apostello” literally means) and thirdly, to carry out the same works our

Lord Himself had been doing. By this time, the apostles would have trembled at

the tall order given to them: to do the same mighty deeds as the Lord. They

would have been happy just basking in His fame and glory, allowing our Lord to

do “the heavy lifting,” while they just did the simple work of managing the

crowds. The fact that the text tells us that the Lord “began to send them out”

suggests that He did not send all Twelve at once, but took time with each pair,

ensuring that they were fully prepared and had the confidence to leave the nest

and take flight into mission. But it is obvious that remaining in the security

of the nest is not an option.

They were not to go alone but in pairs, as

little units of Christian community, since their mission was to gather God’s

people into a community centred on our Lord. Our Lord too chose to share His

mission and ministry with the Twelve. The Church’s experience over the ages has

confirmed the wisdom of this approach. We see evidence of such missionary

partnership and collaboration in the Acts of the Apostles and the epistles of

St Paul. Our Lord understood that a lone missionary is at risk of

discouragement, danger and temptation; but a pair of missionaries can pray

together, encourage and support each other, correct each other’s mistakes and

discern how to deal with problems together. Moreover, under the Law of Moses

the testimony of two witnesses is needed to sustain a criminal charge. Likewise,

the testimony of two or more witnesses would give greater credence to the

gospel.

Our Lord’s instructions regarding their

traveling gear may strike us as rather austere, even by Marie Kondo’s

minimalist standards. The apostles are to take nothing with them other than the

clothing on their backs, sandals on their feet and a walking stick. The lack of

a haversack meant that they could not even accept provisions from others for

the journey - no take-aways! Our Lord’s intention is not so much to encourage

asceticism as such (they are after all to expect and accept hospitality), but

to emphasise that loyalty to the Kingdom of God leaves no room for a prior

attachment to material security. The Apostles had to learn not to rely on their

own resources but on God’s all-sufficient Providence. Because they were

occupying themselves with God’s work, God would occupy Himself with their daily

needs.

The disciples’ lack of material

possessions also lent credibility to their message, since it demonstrated that

they were preaching the gospel out of conviction rather than the desire for

gain. Through their simple lifestyle, they would testify to the Truth which is

proclaimed by St Paul in the second reading: “Blessed be God the Father of our

Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us with all the spiritual blessings of

heaven in Christ.” God’s blessing was more than sufficient.

Though the disciples are instructed to

refuse any material benefit or gain from their work, they are not asked to

refuse hospitality shown to them by those who are receptive to their message.

Hospitality shown to the disciples is synonymous with acceptance of the Gospel

and the stakes involved in accepting or refusing the Gospel are high. Our Lord

equates the response given to His apostles with a response to Himself. To

welcome them, is to welcome Him. And to refuse to listen, is to forfeit His

invitation to eternal life. This, therefore, explains the instruction of

shaking off the dust from their feet. This action was not just a matter of

hygiene. It was a symbolic act of repudiation, meant as a warning to those who

reject the message. For the Jews, the soil of Israel was holy, therefore, upon

re-entering the Holy Land after a journey, they would shake the pagan dust off

their feet as a sign of separating themselves from Gentile ways. Here in this

context, this action pointed to the fact that our Lord was establishing the new

Israel, and those who rejected His message, would also be excluded from the

Kingdom.

How about us? As the Lord chose and sent

out His apostles in those days, He continues to call us and send us out as His

messengers, in these days. What is clear is that we cannot volunteer for this

job. In fact, all of you have been chosen from the beginning, before you were

born. As St Paul reminds us, we have to be chosen, “chosen for (the Lord’s)

greater glory.” Since you have been chosen and you did not apply for the job,

there are no specific credentials. As the prophet Amos reminds us in the first

reading, you do not need to belong to a particular elite group of trained

professionals. The One who chooses you for mission, will empower you for

mission. You are not meant to spend the rest of your lives in the comfort and

security of a risk-free nest. You were never meant to stay put and stay

grounded. You have been chosen because you were meant to be sent – you were

meant to soar. You are born eagles meant to rule the skies, not chickens bound

to the earth.