Eighteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

Vanity seems to be a vice that is not only confined to women but also equally plagues men. Coiffed hair, manicured nails, shiny smooth complexions that scream of repeated facials, and a wardrobe that could put Imelda Marcos’ shoe collection to shame. Vanity in this context means pride but vanity could also mean futility or the pointlessness of our actions and decisions or even life itself. The readings for today address the latter.

People often struggle with these questions, ‘What is life all about?’ ‘What is man’s purpose in this life?’ This is what the Book of Ecclesiastes seeks to address. The book is a philosophical essay attributed to Solomon, the proverbial philosopher king. The author wrote this book from the mistakes he made. He shares his own life’s search. The man had wisdom, riches, horses, armies, and women (that’s an understatement, he had lots of women). Yet, in the end Solomon declared everything to be vanity; in other word, pointless, worthless, meaningless, and purposeless. To pursue vanity is to chase after the wind. Starting with the well-known words, "Vanity of vanities, and all is vanity," and repeating them in the last chapter after having taken us through all the vanities of life, the book contains the important lesson he learns from God, in a sort of ‘roundabout’ way. The Book ends by giving us the antidote of vanity: fear of the Lord and the observance of the moral law. The secret to a purposeful life is: Without God, ‘all is vanity’. But with God, nothing is in vain.

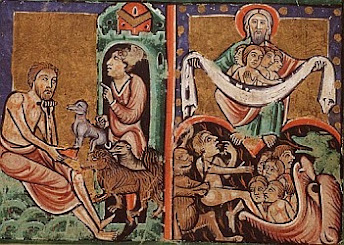

In the gospel, we are given two examples of such earthly vanity - the greedy brother and the rich man in a parable told by the Lord. A man in the crowd puts this request to the Lord, “Master, tell my brother to give me a share of our inheritance.” The question sounds oddly familiar. I’ve seen how family battles over inheritance have set kith against kin. The law of primogeniture says (Num 27:1-11 Deut 21:15) that the first born gets a double portion. If you had two brothers, you divided the estate three ways and the oldest got two parts. So, guess which son this is. His request suggests that he’s the youngest son. Greed, envy and a sense of entitlement have blinded him to place money above kinship.

Understanding the context of the disgruntled brother sets the stage for the parable. There is a comparison and contrast going on between the two characters in the parable and two characters outside the parable. The rich man in the parable is compared to the unhappy younger brother in real life. Christ in real life acts as judge and arbiter, a role taken by God in the parable. Why is the Lord telling this parable about the rich man who had no greed to a greedy man? The Lord builds up the rich man as a good guy, a content man, someone you can easily identify with and would aspire to become. This guy is just the opposite of the disgruntled and unhappy brother. What do we learn? Both men thought that life consisted in ‘things’, that the end and purpose of their lives were the acquisition of such ‘things.’ Selfishness and self-satisfaction have blinded them to the bonds of fraternity and life’s ultimate purpose.

Both the disgruntled younger brother and the contented rich man, in their pursuit for wealth without realising that they risk losing everything in a single moment, proves the point that ‘all is vanity.’ There is a major reversal in the parable – the man who thinks himself clever is proven foolish; the rich man ends up being poor to God. Notice the poetic justice. The rich man, like the entitled brother and like so many of us, so obsessed in storing up treasures for ourselves in this place, acquiring knowledge, wealth, possessions and a list of achievements, had lost sight of the fact that our ultimate goal is our own salvation – making ourselves ‘rich in the sight of God.’ The rich man is not condemned for his wealth or even his greed. He is condemned for forgetting that the ultimate ‘end’ or purpose of his life is salvation. He had made no preparations for this. He was too busy investing in this world and that is the ultimate vanity.

This parable speaks loudly to our generation; it speaks of the purpose of life and what defines it? Have you been defining life in your career, your house, your stock portfolio, in terms of your achievements, the knowledge you possess, the popularity you’ve gained, or the assumption that you will live much longer? What is going to happen when you lose one or more of those things? What happens when you get laid off? What happens when the stock market crashes? What happens when you get some disease which takes away your physical ability? What happens when your friends leave you? What happens if another pandemic hits again? If you define life according to these things, you will be devastated. If these things have become the ‘end’ and purpose of your lives, the goals you are ultimately pursuing, the treasures you are seeking for, then the diagnosis is terminal – vanity of vanities, all is vanity!

St Thomas Aquinas teaches that the real end for which man is made is to be reunited with the goodness of God through virtuous behaviour as well as the use of reason in order to know and love God above all. In the words of St Augustine, “that is our final good, which is loved for its own sake, and all other things for the sake of it.” St Ignatius Loyola in setting out the First Principle and Foundation in his Spiritual Exercises writes, “The human person is created to praise, reverence, and serve God Our Lord, and by doing so, to save his or her soul. All other things on the face of the earth are created for human beings in order to help them pursue the end for which they are created. It follows from this that one must use other created things, in so far as they help towards one's end, and free oneself from them, in so far as they are obstacles to one's end.” Thus, the riches of this life are only potentially good. Their goodness is actualised when they serve the greater good – the glory of God and love of neighbour.

The irony we face is that many people would prefer to love the means rather than the end. Man need not just love bad things in order to be condemned to hell. As the old adage teaches us, “The road to hell is lined with good intentions.” Man can pervert his ultimate end by loving seemingly good things, which seem to bring happiness, and mistake these things for the actual, infinite source of happiness - God. Whenever we choose the lesser goods over the greater Good, whenever we convert the means into the end, whenever our vision is obscured to see beyond what lies immediately before us, then we are in trouble. Everything comes down to the choice: do we choose these things as a means to the end, or do we choose them as a substitute for the end?

Today, the readings challenge us to seek the Source of all Goodness, and not just the goods He dispenses. Desire the God of Miracles, not just hunger for the miracles of God. Long for the giver and not just the gifts. Our thoughts should be on the ultimate prize: Heaven. Things of this earth either lead us to that prize, or they may distract us from that and therefore should be placed in their proper place. When we trudge the road of happy destiny, we must remember that the road is just a means to an end and not the destination itself. Anything else is VANITY!

Showing posts with label vice. Show all posts

Showing posts with label vice. Show all posts

Tuesday, July 29, 2025

Without God, all is vanity

Labels:

Humility,

parable,

pride,

Repentance,

Sin,

Sunday Homily,

vanity,

vice,

Wisdom

Monday, September 19, 2022

Get off your comfy couch!

Twenty Sixth Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

Having gone back to pre-pandemic full capacity, many parishes are awkwardly still witnessing relatively low attendance at Masses. What could be the cause of this? In 2020 and 2021, as our country navigated between complete lockdowns and impossibly stringent SOPs governing public gatherings when some activities were allowed, many of our churches discontinued physical attendance at Masses for long stretches and substituted them with online services. According to the best research, it takes 60–70 days to form a new habit, and we had months of lockdowns and two years of restrictions! That’s plenty of time to form a new habit.

In today’s first reading, the prophet Amos confronts the people of Israel for their spiritual lethargy. He accused them of “lying on ivory beds and sprawling on their divans” while dining on their fatted lambs. He was practically telling them to get off their comfy couches, cease living a sedentary life seated in front of their televisions while gorging on junk food, while ignoring all the critical things happening around them. Apathy or indifference to the cries and plight of the poor, the marginalised, victims of oppression and injustice had become a new habit which they found hard to abandon.

We see a vivid illustration of this in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, in the gospel. The rich man who enjoyed life was condemned to hell at the end of the story whereas Lazarus who suffered in this life, ended up in heaven. The parable is troubling not only for its mention of hell but because the rich man should even end up in hell, though he is not depicted as a horrible person. In fact, the gospel never states that the rich man mistreated poor Lazarus. There is no mention of him acquiring his wealth through unjust means. The point of this parable is not that the rich will be damned and the poor will be saved. Neither is the point of this parable describing a capricious God who likes sending poor souls to hell for the slightest infraction. The problem with the rich man, if you could consider it a problem, is that he was without suffering - he had no inclination of suffering because he had all the luxuries which money could buy. For this reason, he couldn’t feel the pain and the suffering of the beggar Lazarus.

What did the rich man do that was so horrible that he should deserve such a terrible fate as hell? It was simply his apathy. Apathy is indifference habitualised. Examining the Greek root of the word would give us a better understanding of this sin. Apathy comes from two Greek words - “a” which denotes the absence of something, “without”; and “pathos” which means suffering. Therefore, the apathetic person is one who does not know or feel the suffering of another, as opposed to an emphatic person, someone who experiences and feels the suffering of the other.

This was the “crime” of the rich man - he was enclosed in his safe little world of personal enjoyment, insulated by his wealth and comfortable life. Lazarus, therefore, was not treated as a part of suffering humanity but just a part of the landscape. In a word, the rich man was indifferent, and clueless: Indifferent to Lazarus’ plight, indifferent to his hunger, indifferent and clueless to his needs. They were the neighbours who never met.

The indifference which blinded the rich man to the needs of Lazarus and others in this life is a foretaste of what is to come - the chasm that separates heaven from hell, a chasm wide and unbridgeable. There is no passing between the two, ever. In life, a big chasm had opened up between the rich man and Lazarus due to the former’s apathy. Lazarus never showed up on the rich man’s radar. In death, this chasm has grown infinite – in the words of Father Abraham, a ‘great gulf’ separates the minions of hell from the minions of heaven. The chasm which the rich man maintained through his indifference in life had ultimately separated him from God in death. Now, it’s the rich man’s turn to drop off God’s radar. Indifference does not only spell human tragedy, but it also means the lost of beatitude, the lost of salvation.

An apathetic person will not exert any effort to make a difference. He either sees no need to do so or feels so overwhelmed by the problem that he believes that whatever he does will make little to no dent in the issue. He tells himself, “What’s the point?” “Is this my problem?” Or “how does this even concern me?” He will simply sit back and watch events unfold. Unfortunately, this is all that is needed to make one’s journey to hell certain. In the words of the philosopher Edmund Burke, “All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.”

Apathy may seem as insignificant as a tiny crack but it eventually morphs into a great chasm that comes between heaven and hell. Apathy is what makes us ignore the message of the prophets and pass generations and even makes us turn our backs on the One who died and is now risen from the dead. In fact, apathy is what killed the Lord Jesus Christ. Both the fearful Pilate and the jealous High Priests would not have been able to put Jesus to death except for the thousands of people who didn't show up for the crucifixion. They didn't want Jesus dead or alive. They just didn't care. Apathy permitted Hitler to kill six million Jews, and abortion clinics to kill many more millions of babies. Apathy lets thousands die each day of starvation, and billions live each day without knowing Jesus.

At the end of the parable, the rich man asked Abraham to send Lazarus back to earth to warn his brothers to repent so that they would never join him in hell. Abraham told the rich man that if his brothers did not believe in Scripture, neither would they believe a messenger, even if he came straight from heaven. Looks like man’s indifference to his neighbour is finally unmasked – it is merely a cover, a symptom of man’s indifference to God.

Both Amos and our Lord are calling us to get off our comfy couches and to get going. There is no room for couch potato Christians. In fact, being Christian means that we must change our apathy into empathy, we cannot cut ourselves from others because as St Paul reminds us: “If one member suffers, all the members suffer with it.” In his personal letter to Timothy which we heard in our second reading, St Paul outlines what is required of us: “As a man dedicated to God, you must aim to be saintly and religious, filled with faith and love, patient and gentle. Fight the good fight of the faith and win for yourself the eternal life to which you were called when you made your profession and spoke up for the truth in front of many witnesses.”

Having gone back to pre-pandemic full capacity, many parishes are awkwardly still witnessing relatively low attendance at Masses. What could be the cause of this? In 2020 and 2021, as our country navigated between complete lockdowns and impossibly stringent SOPs governing public gatherings when some activities were allowed, many of our churches discontinued physical attendance at Masses for long stretches and substituted them with online services. According to the best research, it takes 60–70 days to form a new habit, and we had months of lockdowns and two years of restrictions! That’s plenty of time to form a new habit.

In today’s first reading, the prophet Amos confronts the people of Israel for their spiritual lethargy. He accused them of “lying on ivory beds and sprawling on their divans” while dining on their fatted lambs. He was practically telling them to get off their comfy couches, cease living a sedentary life seated in front of their televisions while gorging on junk food, while ignoring all the critical things happening around them. Apathy or indifference to the cries and plight of the poor, the marginalised, victims of oppression and injustice had become a new habit which they found hard to abandon.

We see a vivid illustration of this in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, in the gospel. The rich man who enjoyed life was condemned to hell at the end of the story whereas Lazarus who suffered in this life, ended up in heaven. The parable is troubling not only for its mention of hell but because the rich man should even end up in hell, though he is not depicted as a horrible person. In fact, the gospel never states that the rich man mistreated poor Lazarus. There is no mention of him acquiring his wealth through unjust means. The point of this parable is not that the rich will be damned and the poor will be saved. Neither is the point of this parable describing a capricious God who likes sending poor souls to hell for the slightest infraction. The problem with the rich man, if you could consider it a problem, is that he was without suffering - he had no inclination of suffering because he had all the luxuries which money could buy. For this reason, he couldn’t feel the pain and the suffering of the beggar Lazarus.

What did the rich man do that was so horrible that he should deserve such a terrible fate as hell? It was simply his apathy. Apathy is indifference habitualised. Examining the Greek root of the word would give us a better understanding of this sin. Apathy comes from two Greek words - “a” which denotes the absence of something, “without”; and “pathos” which means suffering. Therefore, the apathetic person is one who does not know or feel the suffering of another, as opposed to an emphatic person, someone who experiences and feels the suffering of the other.

This was the “crime” of the rich man - he was enclosed in his safe little world of personal enjoyment, insulated by his wealth and comfortable life. Lazarus, therefore, was not treated as a part of suffering humanity but just a part of the landscape. In a word, the rich man was indifferent, and clueless: Indifferent to Lazarus’ plight, indifferent to his hunger, indifferent and clueless to his needs. They were the neighbours who never met.

The indifference which blinded the rich man to the needs of Lazarus and others in this life is a foretaste of what is to come - the chasm that separates heaven from hell, a chasm wide and unbridgeable. There is no passing between the two, ever. In life, a big chasm had opened up between the rich man and Lazarus due to the former’s apathy. Lazarus never showed up on the rich man’s radar. In death, this chasm has grown infinite – in the words of Father Abraham, a ‘great gulf’ separates the minions of hell from the minions of heaven. The chasm which the rich man maintained through his indifference in life had ultimately separated him from God in death. Now, it’s the rich man’s turn to drop off God’s radar. Indifference does not only spell human tragedy, but it also means the lost of beatitude, the lost of salvation.

An apathetic person will not exert any effort to make a difference. He either sees no need to do so or feels so overwhelmed by the problem that he believes that whatever he does will make little to no dent in the issue. He tells himself, “What’s the point?” “Is this my problem?” Or “how does this even concern me?” He will simply sit back and watch events unfold. Unfortunately, this is all that is needed to make one’s journey to hell certain. In the words of the philosopher Edmund Burke, “All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.”

Apathy may seem as insignificant as a tiny crack but it eventually morphs into a great chasm that comes between heaven and hell. Apathy is what makes us ignore the message of the prophets and pass generations and even makes us turn our backs on the One who died and is now risen from the dead. In fact, apathy is what killed the Lord Jesus Christ. Both the fearful Pilate and the jealous High Priests would not have been able to put Jesus to death except for the thousands of people who didn't show up for the crucifixion. They didn't want Jesus dead or alive. They just didn't care. Apathy permitted Hitler to kill six million Jews, and abortion clinics to kill many more millions of babies. Apathy lets thousands die each day of starvation, and billions live each day without knowing Jesus.

At the end of the parable, the rich man asked Abraham to send Lazarus back to earth to warn his brothers to repent so that they would never join him in hell. Abraham told the rich man that if his brothers did not believe in Scripture, neither would they believe a messenger, even if he came straight from heaven. Looks like man’s indifference to his neighbour is finally unmasked – it is merely a cover, a symptom of man’s indifference to God.

Both Amos and our Lord are calling us to get off our comfy couches and to get going. There is no room for couch potato Christians. In fact, being Christian means that we must change our apathy into empathy, we cannot cut ourselves from others because as St Paul reminds us: “If one member suffers, all the members suffer with it.” In his personal letter to Timothy which we heard in our second reading, St Paul outlines what is required of us: “As a man dedicated to God, you must aim to be saintly and religious, filled with faith and love, patient and gentle. Fight the good fight of the faith and win for yourself the eternal life to which you were called when you made your profession and spoke up for the truth in front of many witnesses.”

Labels:

apathy,

Discipleship,

parable,

Poor,

Sunday Homily,

vice

Friday, October 4, 2019

Fan into flame the gift God has given you

Twenty Seventh

Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

One of my favourite memes which I often send to

friends after a busy and tiring day is that of this chubby boy slump over his

desk with his head resting on folded arms, with the following caption, “This is

me every day, and not just on a Sunday.” Weariness and exhaustion in life are

all too common. We go to work day after day, drive forty minutes plus, pick up

the kids from school, drive home, make dinner, help with homework or send them

for tuition, and maybe live with someone we barely talk to, only to start it

all again tomorrow. Sounds familiar? Yes, even the most extroverted and highly

motivated would arrive at a point in life where they are almost on auto-pilot,

repeating mindless and meaningless routine. If this is true of your personal

life, can our spiritual life be any different? It is at this stage that for

many, faith no longer makes sense. In The Everlasting Man, G. K. Chesterton has

his finger on the problem: “Pessimism is not in being tired of evil but in

being tired of good. Despair does not lie in being weary of suffering, but in

being weary of joy.”

The early Church fathers had a name for this affliction

– acedia, which later got translated into “sloth”, one of the seven deadly

sins. The association with sloth unfortunately leads many to equate acedia with

pure laziness. But there is more to it. The Catechism teaches us that: “acedia

or spiritual sloth goes so far as to refuse the joy that comes from God, and to

be repelled by divine goodness” (# 2094).

Dorothy Sayers, who wrote an entire book on the subject, describes it as

“a sin that believes in nothing, cares for nothing, seeks to know nothing,

interferes with nothing, enjoys nothing, hates nothing, finds purpose in nothing,

lives for nothing, and remains alive because there is nothing for which it will

die.” In short, “sloth” does not mean inactivity but rather apathy. Instead of

finding anything exciting, we get bored with everything.

What do we do when apathy sets in to our faith life?

The problem and remedy seems to be addressed by this week’s readings. Faith is

the motif in each reading. The seldom-referenced prophet Habakkuk had grown

frustrated with the lack of faith evidenced in his people's behaviour and

responsiveness to God. They had grown spiritually slothful and now the prophet

himself is tempted to follow suit. But God assures him, however, that his prayers

are heard and God never disappoints. Perseverance would be the first remedy to

acedia. We should keep praying, even when we don’t feel like it. We should keep

going for mass and confession, even when we seem to get nothing out of it. As

the Lord assured Habakkuk, “if it comes slowly wait, for come it will, without

fail,” because “the upright man will live by his faithfulness.”

Similarly in the gospel, when the disciples learned

more about the demands of discipleship, they feared they did not have the faith

to meet the challenges that came with it. The heaviness of discipleship weights

down on them. To that end, they beg, “increase our faith,” a frank admission their

profound lack. But the problem is that faith

is not quantifiable. Nevertheless, it is the power that inspires us, helps us

to persevere, enables us to struggle and not lose heart, and keeps us ever

mindful of God’s abiding presence. That is why our Lord uses the images of the

mustard seed and the mulberry tree to graphically illustrate the power of faith,

even the tiniest spark of it, can move the unmovable and accomplish what appears

to be impossible.

At first glance, it might appear that the Lord was

being sarcastic. But this was not His intention. In fact, He clearly knew and

understood their weaknesses, but He also wanted them to understand that even a

little faith goes a long way. His parable about the servant seems to say that

faith is not a reward for the spiritually proficient; rather, faith is the

requisite for every disciple. And when we have faith, we are merely doing our

job as disciples and should seek no reward.

Yes, even a little faith can go a long way. Faith

begets faith. Or, as St. Thomas Aquinas noted, “Faith does not quench desire,

but inflames it.” True faith is like a small snowball poised at the top of a

long slope, waiting to be pushed so it might then grow as it picks up speed.

But that snowball is always first formed and moved by God. Faith is first and

foremost a gift from God. But faith is also a response. When we respond in

obedience to God and His gift, faith grows. This is because faith is also a habit,

a power or capacity that gets stronger when it is exercised and atrophies when

it is not. So faith is like a spiritual

muscle. The way you develop faith is, to

exercise it regularly and to do so against ever increasing resistance. Don’t

expect faith to get easier. It necessarily gets harder because the only way

faith grows is to be challenged. If you

ask for faith, know that this means giving the Lord permission to put more

weight on the bar. If we wish to grow in

faith and resist the vice of acedia or spiritual sloth, we must be ready to

discipline ourselves. For, as St. Paul says, “God did not give us a spirit of

timidity, but a spirit of power and love and self-control (2 Timothy 1:8).”

That brings us full circle back to St Paul in the

second reading and the wisdom he shared with his friend and colleague, Timothy.

As he reminded Timothy, our faith must be tended, stirred and fed like a flame.

Our Christian faith can be likened to hot coals which would make a fire when

fanned but become cold and useless if left alone. Many of us Catholics were

baptised as infants, thus becoming Christians before we knew anything at all.

Many of us grew up without properly tending that initial spark of faith that

was given to us at baptism or we had allowed the pressures and distractions of

life to reduce our faith to cold ashes. The result being so many have left the

faith of our childhood, the faith of our parents, believing this is no longer

relevant.

How do we fan into a flame God's gift of faith that

has been kindled within us? Fanning our faith into a flame implies that we

respond to the grace of God in us. It is achieved through daily communion with

God in prayers, taking time to prayerfully study His Word and frequenting the

Sacraments of Penance and the Holy Eucharist. It means reading good spiritual

books and attending good formations to deepen our faith. Being immersed in a

faith community and community life, is essential for our growth in faith. As we open our hearts to God in these ways,

He strengthens our faith, allowing the seed of faith planted in us to blossom.

But when we cease doing these things, we would soon find our enthusiasm for

anything spiritual diminishing.

Most of us need an occasional shot in the arm to keep

our faith strong and vibrant. But this does not mean that we should be constantly

searching for extraordinary experiences that give us an emotional high. Growth

in friendship with God does not happen only in the special, uplifting moments.

It is through our daily efforts to be faithful to God, to live our faith in the

everyday, with the help of the Sacraments, that our bond with God is

strengthened.

Yes, we need to fan into flame the gift of faith God

has given us. But in order for it to really catch fire, we need to step out in

faith. Every step of faith that we take is like the oxygen added to the fire to

keep it blazing! Our effort, feeble though it may seem to us (like a tiny

insignificant mustard seed), works like a bellows blowing air onto the fire

until it is a blazing bonfire. So, let us fan the flame of the Spirit. Let His

fire burn away all doubt and hesitation, all sloth and apathy, so that you can

become a beacon of faith, hope, and love for the people around you. As Pope

Francis constantly reminds us – what the Church needs more than ever today, are

joyful witnesses full of enthusiasm rather than someone who had just walked out

of a funeral.

Labels:

Discipleship,

Faith,

parable,

Sin,

Sunday Homily,

vice,

virtues

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)