Twenty First Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

Our Lord gives us a frightening parable of judgment in answer to the question: “Sir, will there be only a few saved?” You may think that this question is ludicrous, that it’s making a mountain out of a molehill. You may even volunteer to beat Jesus in giving the answer to this man: “of course not! Don’t you know that everyone’s going to be saved?” Although official Catholic teaching and Protestant understanding of salvation shares many points in common, this is where they defer – at least in popular imagination. Many Catholics believe that everyone is going to heaven while Protestants think that almost everyone, unless you are a true Christian believer, is going to hell.

When Protestants ask Catholics if they have been saved, the question would most likely be met with a stunned look on the part of the Catholic or an admission that he has never thought about this before. This comes as good news to the Protestant as he can now confidently proselytise the Catholic and ensure that the latter is saved by becoming a Bible believing, faith professing Protestant Christian. For many Protestants, one becomes a Christian by merely making a confession of faith in Jesus as Saviour and Lord. Baptism comes later but isn’t necessary for our salvation. I guess the reason why most Catholics are not prepared with an answer to that question is that salvation or rather, heaven, is something they often take for granted. Why worry about this moot issue when we can all get to heaven?

Perhaps, this common Catholic misunderstanding of universal salvation can be far more dangerous than the Protestant heretical position of being saved once and for all by grace alone. When you believe that salvation is guaranteed whether you’ve lived a good life or not in conformity to Christ’s teachings and God’s will, it is called the sin of presumption, which is a sin against hope. On presumption, the Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches: “There are two kinds of presumption. Either man presumes upon his own capacities, (hoping to be able to save himself without help from on high), or he presumes upon God’s almighty power or his mercy (hoping to obtain his forgiveness without conversion and glory without merit).” (CCC 2092) When people are presumptuous, they are living in denial of the truth. And because they are living in denial, they will not repent of his or her own sin.

I have often tried to explain the Catholic position on salvation to both Catholics and non-Catholics by using this analogy of being shipwrecked in the middle of an ocean. We’re like the survivors of a shipwreck in a storm out in mid-ocean. Just imagine being in this situation. The nearest shoreline is just too far for even the strongest swimmer. You won’t be able to save yourself. The only way that we can get out of this situation is that we are saved. And the good news is that we have been rescued from drowning by the Lord Jesus Himself, our Saviour, and welcomed onboard the ship we call the Church. That ship is now taking us to a safe harbour — our home in heaven with God. For Protestants, being saved is the end of the story and they don’t even believe you need a boat for this. But for Catholics, baptism, being rescued into the ship is just the first step. But we’re not home yet.

You could say, then, that we’ve been “saved” in the sense of being rescued and taken aboard a safe vessel. But we can’t really speak of being “saved” in the full sense until we reach our destination. We must humbly admit that we haven’t yet arrived at final perfection. Meanwhile, we also must recognise the sobering possibility that — God forbid — we could choose someday to jump overboard again. Salvation isn’t guaranteed just because of something we’ve done in the past. We continue to have a free will, which is part of God’s likeness in us. So we still have the ability to turn away from God again. It’s a chilling possibility. But it shouldn’t make us perpetually worried that we’ll be damned despite our best efforts to grow in grace. We can be confident that God desires our salvation, and He’s faithful to help us. And He does so by providing us with the Sacraments. If we’re tempted to forsake Him, He’ll grant us the power to resist that temptation. He will even send a lifeboat to rescue us again through the sacrament of penance. Even so, the choice is still ours.

If we can’t be certain as to the final statistics on the population of heaven and hell, there are some things we can know with certainty because our Lord has revealed this to us, leaving no room for speculation.

Firstly, Hell is real and it is everlasting. We may not hear much about hell these days and we may not even like to, but silence on the subject does not make the reality of Hell go away. Infact the denial of hell leads ultimately to the trivialising of heaven. But a healthy understanding of the pains and horrors of hell, will lead us to an authentic appreciation of the joys of heaven.

Secondly, life is a series of choices. We can either choose to take a) the difficult path that leads to the narrow gate and life, and b) the broad path which leads to the wide gate and destruction. The narrow path is the way of the Cross which our Lord undertook, and we must follow in our respective way. The second reading from Hebrews reminds us that the suffering we endure is not the result of a cruel sadistic God but because “suffering is part of your training; God is treating you as his sons.” It is a popular error of our time to believe that it does not matter which road one takes. Some believe that all roads are like spokes on a wheel, all leading to the same place—Heaven. In fact, we make choices every day that draw us closer to God or lead us farther away from Him. That’s why simply believing in Jesus isn’t enough. Friendship with God, like friendship of any kind, is more than just getting acquainted. It involves making a series of choices to love over the long term, so that a committed relationship grows. Faith is useless then, without good works. God must have our active cooperation, because both our mind and our will — the full likeness of God — must be renewed if we’re to be saved in the end.

Thirdly, there is an urgency to making the right decision. Time is of the essence. No time for procrastination or putting off what must be done today. Our Lord speaks of the time when the householder will arise, shut and lock the door. That corridor of opportunity will not always be opened and if mistaken that it is always open may lead to our destruction.

Finally, we must make our own salvation and the salvation of all those around us, our top priority in this life. As the old Catholic adage reminds us: “the salvation of souls is the supreme law!” Nothing else ranks anywhere close in importance—not health, wealth, career, popularity, possessions or acclaim by others. Know what you must do to be saved and work out that salvation in fear and trembling.

Today, let us not be guilty of the sin of presumption that Heaven is guaranteed no matter how or which way we live our lives. Truly, our Lord Jesus is the Divine Mercy. Truly, He wishes and desires for all of us to be saved. But more urgently, He wants us to understand that there can be no other way to salvation other than passing through the Narrow Door. He is that Narrow Doorway to Heaven. It is the Gospel of Christ, paid by His own blood on the cross. It is demanding. It demands that we make the ultimate sacrifice by turning our backs on all the false gods that have become the defining elements in our lives. It demands repentance on our part.

Showing posts with label Sin. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Sin. Show all posts

Monday, August 18, 2025

Are you saved?

Labels:

Grace,

heaven,

Hell,

Last Things,

parable,

presumption,

Protestant,

Sacraments,

salvation,

Sin,

Sunday Homily

Tuesday, July 29, 2025

Without God, all is vanity

Eighteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

Vanity seems to be a vice that is not only confined to women but also equally plagues men. Coiffed hair, manicured nails, shiny smooth complexions that scream of repeated facials, and a wardrobe that could put Imelda Marcos’ shoe collection to shame. Vanity in this context means pride but vanity could also mean futility or the pointlessness of our actions and decisions or even life itself. The readings for today address the latter.

People often struggle with these questions, ‘What is life all about?’ ‘What is man’s purpose in this life?’ This is what the Book of Ecclesiastes seeks to address. The book is a philosophical essay attributed to Solomon, the proverbial philosopher king. The author wrote this book from the mistakes he made. He shares his own life’s search. The man had wisdom, riches, horses, armies, and women (that’s an understatement, he had lots of women). Yet, in the end Solomon declared everything to be vanity; in other word, pointless, worthless, meaningless, and purposeless. To pursue vanity is to chase after the wind. Starting with the well-known words, "Vanity of vanities, and all is vanity," and repeating them in the last chapter after having taken us through all the vanities of life, the book contains the important lesson he learns from God, in a sort of ‘roundabout’ way. The Book ends by giving us the antidote of vanity: fear of the Lord and the observance of the moral law. The secret to a purposeful life is: Without God, ‘all is vanity’. But with God, nothing is in vain.

In the gospel, we are given two examples of such earthly vanity - the greedy brother and the rich man in a parable told by the Lord. A man in the crowd puts this request to the Lord, “Master, tell my brother to give me a share of our inheritance.” The question sounds oddly familiar. I’ve seen how family battles over inheritance have set kith against kin. The law of primogeniture says (Num 27:1-11 Deut 21:15) that the first born gets a double portion. If you had two brothers, you divided the estate three ways and the oldest got two parts. So, guess which son this is. His request suggests that he’s the youngest son. Greed, envy and a sense of entitlement have blinded him to place money above kinship.

Understanding the context of the disgruntled brother sets the stage for the parable. There is a comparison and contrast going on between the two characters in the parable and two characters outside the parable. The rich man in the parable is compared to the unhappy younger brother in real life. Christ in real life acts as judge and arbiter, a role taken by God in the parable. Why is the Lord telling this parable about the rich man who had no greed to a greedy man? The Lord builds up the rich man as a good guy, a content man, someone you can easily identify with and would aspire to become. This guy is just the opposite of the disgruntled and unhappy brother. What do we learn? Both men thought that life consisted in ‘things’, that the end and purpose of their lives were the acquisition of such ‘things.’ Selfishness and self-satisfaction have blinded them to the bonds of fraternity and life’s ultimate purpose.

Both the disgruntled younger brother and the contented rich man, in their pursuit for wealth without realising that they risk losing everything in a single moment, proves the point that ‘all is vanity.’ There is a major reversal in the parable – the man who thinks himself clever is proven foolish; the rich man ends up being poor to God. Notice the poetic justice. The rich man, like the entitled brother and like so many of us, so obsessed in storing up treasures for ourselves in this place, acquiring knowledge, wealth, possessions and a list of achievements, had lost sight of the fact that our ultimate goal is our own salvation – making ourselves ‘rich in the sight of God.’ The rich man is not condemned for his wealth or even his greed. He is condemned for forgetting that the ultimate ‘end’ or purpose of his life is salvation. He had made no preparations for this. He was too busy investing in this world and that is the ultimate vanity.

This parable speaks loudly to our generation; it speaks of the purpose of life and what defines it? Have you been defining life in your career, your house, your stock portfolio, in terms of your achievements, the knowledge you possess, the popularity you’ve gained, or the assumption that you will live much longer? What is going to happen when you lose one or more of those things? What happens when you get laid off? What happens when the stock market crashes? What happens when you get some disease which takes away your physical ability? What happens when your friends leave you? What happens if another pandemic hits again? If you define life according to these things, you will be devastated. If these things have become the ‘end’ and purpose of your lives, the goals you are ultimately pursuing, the treasures you are seeking for, then the diagnosis is terminal – vanity of vanities, all is vanity!

St Thomas Aquinas teaches that the real end for which man is made is to be reunited with the goodness of God through virtuous behaviour as well as the use of reason in order to know and love God above all. In the words of St Augustine, “that is our final good, which is loved for its own sake, and all other things for the sake of it.” St Ignatius Loyola in setting out the First Principle and Foundation in his Spiritual Exercises writes, “The human person is created to praise, reverence, and serve God Our Lord, and by doing so, to save his or her soul. All other things on the face of the earth are created for human beings in order to help them pursue the end for which they are created. It follows from this that one must use other created things, in so far as they help towards one's end, and free oneself from them, in so far as they are obstacles to one's end.” Thus, the riches of this life are only potentially good. Their goodness is actualised when they serve the greater good – the glory of God and love of neighbour.

The irony we face is that many people would prefer to love the means rather than the end. Man need not just love bad things in order to be condemned to hell. As the old adage teaches us, “The road to hell is lined with good intentions.” Man can pervert his ultimate end by loving seemingly good things, which seem to bring happiness, and mistake these things for the actual, infinite source of happiness - God. Whenever we choose the lesser goods over the greater Good, whenever we convert the means into the end, whenever our vision is obscured to see beyond what lies immediately before us, then we are in trouble. Everything comes down to the choice: do we choose these things as a means to the end, or do we choose them as a substitute for the end?

Today, the readings challenge us to seek the Source of all Goodness, and not just the goods He dispenses. Desire the God of Miracles, not just hunger for the miracles of God. Long for the giver and not just the gifts. Our thoughts should be on the ultimate prize: Heaven. Things of this earth either lead us to that prize, or they may distract us from that and therefore should be placed in their proper place. When we trudge the road of happy destiny, we must remember that the road is just a means to an end and not the destination itself. Anything else is VANITY!

Vanity seems to be a vice that is not only confined to women but also equally plagues men. Coiffed hair, manicured nails, shiny smooth complexions that scream of repeated facials, and a wardrobe that could put Imelda Marcos’ shoe collection to shame. Vanity in this context means pride but vanity could also mean futility or the pointlessness of our actions and decisions or even life itself. The readings for today address the latter.

People often struggle with these questions, ‘What is life all about?’ ‘What is man’s purpose in this life?’ This is what the Book of Ecclesiastes seeks to address. The book is a philosophical essay attributed to Solomon, the proverbial philosopher king. The author wrote this book from the mistakes he made. He shares his own life’s search. The man had wisdom, riches, horses, armies, and women (that’s an understatement, he had lots of women). Yet, in the end Solomon declared everything to be vanity; in other word, pointless, worthless, meaningless, and purposeless. To pursue vanity is to chase after the wind. Starting with the well-known words, "Vanity of vanities, and all is vanity," and repeating them in the last chapter after having taken us through all the vanities of life, the book contains the important lesson he learns from God, in a sort of ‘roundabout’ way. The Book ends by giving us the antidote of vanity: fear of the Lord and the observance of the moral law. The secret to a purposeful life is: Without God, ‘all is vanity’. But with God, nothing is in vain.

In the gospel, we are given two examples of such earthly vanity - the greedy brother and the rich man in a parable told by the Lord. A man in the crowd puts this request to the Lord, “Master, tell my brother to give me a share of our inheritance.” The question sounds oddly familiar. I’ve seen how family battles over inheritance have set kith against kin. The law of primogeniture says (Num 27:1-11 Deut 21:15) that the first born gets a double portion. If you had two brothers, you divided the estate three ways and the oldest got two parts. So, guess which son this is. His request suggests that he’s the youngest son. Greed, envy and a sense of entitlement have blinded him to place money above kinship.

Understanding the context of the disgruntled brother sets the stage for the parable. There is a comparison and contrast going on between the two characters in the parable and two characters outside the parable. The rich man in the parable is compared to the unhappy younger brother in real life. Christ in real life acts as judge and arbiter, a role taken by God in the parable. Why is the Lord telling this parable about the rich man who had no greed to a greedy man? The Lord builds up the rich man as a good guy, a content man, someone you can easily identify with and would aspire to become. This guy is just the opposite of the disgruntled and unhappy brother. What do we learn? Both men thought that life consisted in ‘things’, that the end and purpose of their lives were the acquisition of such ‘things.’ Selfishness and self-satisfaction have blinded them to the bonds of fraternity and life’s ultimate purpose.

Both the disgruntled younger brother and the contented rich man, in their pursuit for wealth without realising that they risk losing everything in a single moment, proves the point that ‘all is vanity.’ There is a major reversal in the parable – the man who thinks himself clever is proven foolish; the rich man ends up being poor to God. Notice the poetic justice. The rich man, like the entitled brother and like so many of us, so obsessed in storing up treasures for ourselves in this place, acquiring knowledge, wealth, possessions and a list of achievements, had lost sight of the fact that our ultimate goal is our own salvation – making ourselves ‘rich in the sight of God.’ The rich man is not condemned for his wealth or even his greed. He is condemned for forgetting that the ultimate ‘end’ or purpose of his life is salvation. He had made no preparations for this. He was too busy investing in this world and that is the ultimate vanity.

This parable speaks loudly to our generation; it speaks of the purpose of life and what defines it? Have you been defining life in your career, your house, your stock portfolio, in terms of your achievements, the knowledge you possess, the popularity you’ve gained, or the assumption that you will live much longer? What is going to happen when you lose one or more of those things? What happens when you get laid off? What happens when the stock market crashes? What happens when you get some disease which takes away your physical ability? What happens when your friends leave you? What happens if another pandemic hits again? If you define life according to these things, you will be devastated. If these things have become the ‘end’ and purpose of your lives, the goals you are ultimately pursuing, the treasures you are seeking for, then the diagnosis is terminal – vanity of vanities, all is vanity!

St Thomas Aquinas teaches that the real end for which man is made is to be reunited with the goodness of God through virtuous behaviour as well as the use of reason in order to know and love God above all. In the words of St Augustine, “that is our final good, which is loved for its own sake, and all other things for the sake of it.” St Ignatius Loyola in setting out the First Principle and Foundation in his Spiritual Exercises writes, “The human person is created to praise, reverence, and serve God Our Lord, and by doing so, to save his or her soul. All other things on the face of the earth are created for human beings in order to help them pursue the end for which they are created. It follows from this that one must use other created things, in so far as they help towards one's end, and free oneself from them, in so far as they are obstacles to one's end.” Thus, the riches of this life are only potentially good. Their goodness is actualised when they serve the greater good – the glory of God and love of neighbour.

The irony we face is that many people would prefer to love the means rather than the end. Man need not just love bad things in order to be condemned to hell. As the old adage teaches us, “The road to hell is lined with good intentions.” Man can pervert his ultimate end by loving seemingly good things, which seem to bring happiness, and mistake these things for the actual, infinite source of happiness - God. Whenever we choose the lesser goods over the greater Good, whenever we convert the means into the end, whenever our vision is obscured to see beyond what lies immediately before us, then we are in trouble. Everything comes down to the choice: do we choose these things as a means to the end, or do we choose them as a substitute for the end?

Today, the readings challenge us to seek the Source of all Goodness, and not just the goods He dispenses. Desire the God of Miracles, not just hunger for the miracles of God. Long for the giver and not just the gifts. Our thoughts should be on the ultimate prize: Heaven. Things of this earth either lead us to that prize, or they may distract us from that and therefore should be placed in their proper place. When we trudge the road of happy destiny, we must remember that the road is just a means to an end and not the destination itself. Anything else is VANITY!

Labels:

Humility,

parable,

pride,

Repentance,

Sin,

Sunday Homily,

vanity,

vice,

Wisdom

Monday, July 7, 2025

How have we come to salvation?

Fifteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Year C

Whenever an anecdotal story is shared, it begs the question: “what’s the moral of the story?” Most homilies on the parable of the Good Samaritan would most likely attempt to provide the answer to this question and it would often sound like this: “do good to others, even those who are not your friends.” If it was only that simple, this would be the end of my homily. But the truth is that there is more than meets the eye in this most familiar parable of our Lord.

The context of our Lord telling this parable is that it serves as an answer given to a question posed by a lawyer, not to be confused with modern advocates and solicitors. The lawyer here is also known as a scribe, an academician or scholar, who has devoted his life to studying the Mosaic Law in order to provide a correct interpretation and application of the Law to the daily lives of fellow Jews. The question he poses is not just a valid question but one of utmost importance because it has to do with our ultimate purpose in life: “Master, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” That is the question that every religion and every philosophy has ever attempted to answer. Though a valid question and one which all of us should want to know the answer, the evangelist tells us that his motives are less than pure. It is said that he asked this question “to disconcert” the Lord. It was a trap. In fact, the lawyer already knows the answer to his question. But knowledge of the answer does not necessarily mean that one is living the answer, which is what the Lord wishes to expose here. He speaks eloquently of love but has no love for our Lord or even his audience. And so our Lord tells him that even though he has answered right by citing the two-fold commandments of love, there is still something missing in his answer: “do this and life is yours.”

Having been found out by the Lord and therefore, humiliated, he continues to try to “justify” himself by nit-picking: “And who is my neighbour?” In other words, the lawyer seeks to corner Jesus by forcing Him to tell who is deserving of our love. The surprising thing about the parable of the Good Samaritan is that it does not really provide a direct answer to the lawyer’s second question of defining one’s neighbour. If Jesus had been asked, “How should we treat our neighbours?” and had responded with this story, perhaps “Be like the Good Samaritan” would be an acceptable interpretation. Such a moralistic interpretation would mean that the “neighbour” in question is not the one who is deserving of our love but the one who demonstrates love. It turns the question completely around. But, the intention of the parable is more than a mere call to display altruistic behaviour to one’s neighbour. It addressed a more vital question: how have we come to salvation?

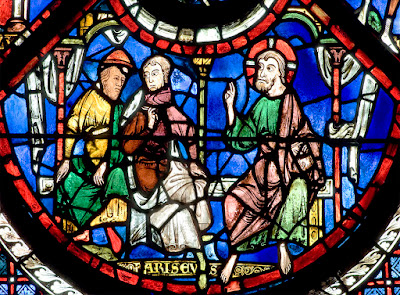

According to the Fathers of the Church, this parable is as an impressive allegory of the fall and redemption of all mankind – how we came to be saved! This is clearly depicted in a beautiful stained-glass window in the famous 12th-century cathedral in Chartres, France. This window is divided into two parts. At the upper section of the window, we see the story of Adam and Eve's expulsion from the Garden of Eden, at the bottom section of the window, the parable of the Good Samaritan; therefore, the narrative of the creation and fall of man is juxtaposed with that of the Good Samaritan. What does the parable of the Good Samaritan have to do with the Fall of Adam and Eve? Where did this association originate?

The roots of this allegorical interpretation reach deeply into the earliest Christian Tradition. Various Fathers of the Church saw Jesus Himself in the Good Samaritan; and in the man who fell among thieves they saw Adam, a representative of mankind, our very humanity wounded and disoriented on account of its sins. For example, Origen employed the following allegory: Jerusalem represents heaven; Jericho, the world; the robbers, the devil and his minions; the Priest represents the Law, and the Levite the Prophets; the Good Samaritan, Christ; the ass, Christ’s body carrying fallen man to the inn which becomes the Church. Even the Samaritan’s promise to return translates into Christ’s triumphant return at the Parousia.

Understanding this parable allegorically adds an eternal perspective and value to its message. It certainly takes it beyond the cliché ‘moral of the story’: ‘Be a Good Samaritan.’ Before we can become Good Samaritans to help others, we need to remember that we have been saved by the Good Samaritan – the story helps us become aware of where we have come from, how we have fallen into our present state through sin, and how Christ has come to save us, the Sacraments of grace continue to sanctify us and the Church continues to nurture and heal us. In other words, this Christological interpretation shifts the focus from man to God: from ‘justification’, how do we work out our salvation, to sanctification, how does Christ save us and continue to sanctify us. As the old patristic adage affirms: “God became Man so that men may become gods.” It moves us away from the humanistic mode of being saviours of the world to a more humble recognition that we are indeed in need of salvation ourselves - we are that fallen man by the wayside waiting for a Saviour and we have found Him in Christ!

In a rich irony, we move from being identified with the priest and the Levite who were solely concerned over their personal salvation but never perfectly love others “as ourselves,” much less our enemies, to being identified with the traveller in desperate need of salvation. The Lord intends the parable itself to leave us beaten and bloodied, lying in a ditch, like the man in the story. We are the needy, unable to do anything to help ourselves. We are the broken people, beaten up by life, robbed of hope. But then Jesus comes. Unlike the Priest and Levite, He doesn’t avoid us. He crosses the street—from heaven to earth—comes into our mess, gets His hands dirty. At great cost to Himself on the cross, He heals our wounds, covers our nakedness, and loves us with a no-strings-attached love. He carries us personally to the shelter of the Church where we find rest, where our wounds are tended and healed. He brings us to the Father and promises that His “help” is not simply a ‘one-time’ gift—rather, it’s a gift that will forever cover “the charges” we incur and will sustain us until He returns in glory.

So the parable is not just a moralistic tale of what we must do as Christians but the history of salvation in a nutshell - it tells us what Christ has done for us and continues to do for us?

The context puts the Lord’s final exhortation to “go and do the same yourself” in perspective. It puts every work of charity, gesture of kindness, expression of hospitality on our part within the greater picture of the wonderful story of salvation. The great commandment of love isn’t about some altruistic humanistic project – us saving the world. Reaching out to others, especially to those who labour under the heavy load of toil and suffering, is not just an act of goodness. It is a participation in the economy of God’s salvation – God saving the world through us and in spite of us. We can love only because we have been loved. We can only heal because we have been healed and continue to be healed by the Good Samaritan Himself, Jesus Christ. To understand what it means to love, does not mean attempting to be a ‘Good Samaritan.’ To understand what it means to love, we need to gaze upon Jesus Christ, He is the ‘Good Samaritan’ who has laid down His life and atoned for our sins. This is eternal life!

Whenever an anecdotal story is shared, it begs the question: “what’s the moral of the story?” Most homilies on the parable of the Good Samaritan would most likely attempt to provide the answer to this question and it would often sound like this: “do good to others, even those who are not your friends.” If it was only that simple, this would be the end of my homily. But the truth is that there is more than meets the eye in this most familiar parable of our Lord.

The context of our Lord telling this parable is that it serves as an answer given to a question posed by a lawyer, not to be confused with modern advocates and solicitors. The lawyer here is also known as a scribe, an academician or scholar, who has devoted his life to studying the Mosaic Law in order to provide a correct interpretation and application of the Law to the daily lives of fellow Jews. The question he poses is not just a valid question but one of utmost importance because it has to do with our ultimate purpose in life: “Master, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” That is the question that every religion and every philosophy has ever attempted to answer. Though a valid question and one which all of us should want to know the answer, the evangelist tells us that his motives are less than pure. It is said that he asked this question “to disconcert” the Lord. It was a trap. In fact, the lawyer already knows the answer to his question. But knowledge of the answer does not necessarily mean that one is living the answer, which is what the Lord wishes to expose here. He speaks eloquently of love but has no love for our Lord or even his audience. And so our Lord tells him that even though he has answered right by citing the two-fold commandments of love, there is still something missing in his answer: “do this and life is yours.”

Having been found out by the Lord and therefore, humiliated, he continues to try to “justify” himself by nit-picking: “And who is my neighbour?” In other words, the lawyer seeks to corner Jesus by forcing Him to tell who is deserving of our love. The surprising thing about the parable of the Good Samaritan is that it does not really provide a direct answer to the lawyer’s second question of defining one’s neighbour. If Jesus had been asked, “How should we treat our neighbours?” and had responded with this story, perhaps “Be like the Good Samaritan” would be an acceptable interpretation. Such a moralistic interpretation would mean that the “neighbour” in question is not the one who is deserving of our love but the one who demonstrates love. It turns the question completely around. But, the intention of the parable is more than a mere call to display altruistic behaviour to one’s neighbour. It addressed a more vital question: how have we come to salvation?

According to the Fathers of the Church, this parable is as an impressive allegory of the fall and redemption of all mankind – how we came to be saved! This is clearly depicted in a beautiful stained-glass window in the famous 12th-century cathedral in Chartres, France. This window is divided into two parts. At the upper section of the window, we see the story of Adam and Eve's expulsion from the Garden of Eden, at the bottom section of the window, the parable of the Good Samaritan; therefore, the narrative of the creation and fall of man is juxtaposed with that of the Good Samaritan. What does the parable of the Good Samaritan have to do with the Fall of Adam and Eve? Where did this association originate?

The roots of this allegorical interpretation reach deeply into the earliest Christian Tradition. Various Fathers of the Church saw Jesus Himself in the Good Samaritan; and in the man who fell among thieves they saw Adam, a representative of mankind, our very humanity wounded and disoriented on account of its sins. For example, Origen employed the following allegory: Jerusalem represents heaven; Jericho, the world; the robbers, the devil and his minions; the Priest represents the Law, and the Levite the Prophets; the Good Samaritan, Christ; the ass, Christ’s body carrying fallen man to the inn which becomes the Church. Even the Samaritan’s promise to return translates into Christ’s triumphant return at the Parousia.

Understanding this parable allegorically adds an eternal perspective and value to its message. It certainly takes it beyond the cliché ‘moral of the story’: ‘Be a Good Samaritan.’ Before we can become Good Samaritans to help others, we need to remember that we have been saved by the Good Samaritan – the story helps us become aware of where we have come from, how we have fallen into our present state through sin, and how Christ has come to save us, the Sacraments of grace continue to sanctify us and the Church continues to nurture and heal us. In other words, this Christological interpretation shifts the focus from man to God: from ‘justification’, how do we work out our salvation, to sanctification, how does Christ save us and continue to sanctify us. As the old patristic adage affirms: “God became Man so that men may become gods.” It moves us away from the humanistic mode of being saviours of the world to a more humble recognition that we are indeed in need of salvation ourselves - we are that fallen man by the wayside waiting for a Saviour and we have found Him in Christ!

In a rich irony, we move from being identified with the priest and the Levite who were solely concerned over their personal salvation but never perfectly love others “as ourselves,” much less our enemies, to being identified with the traveller in desperate need of salvation. The Lord intends the parable itself to leave us beaten and bloodied, lying in a ditch, like the man in the story. We are the needy, unable to do anything to help ourselves. We are the broken people, beaten up by life, robbed of hope. But then Jesus comes. Unlike the Priest and Levite, He doesn’t avoid us. He crosses the street—from heaven to earth—comes into our mess, gets His hands dirty. At great cost to Himself on the cross, He heals our wounds, covers our nakedness, and loves us with a no-strings-attached love. He carries us personally to the shelter of the Church where we find rest, where our wounds are tended and healed. He brings us to the Father and promises that His “help” is not simply a ‘one-time’ gift—rather, it’s a gift that will forever cover “the charges” we incur and will sustain us until He returns in glory.

So the parable is not just a moralistic tale of what we must do as Christians but the history of salvation in a nutshell - it tells us what Christ has done for us and continues to do for us?

The context puts the Lord’s final exhortation to “go and do the same yourself” in perspective. It puts every work of charity, gesture of kindness, expression of hospitality on our part within the greater picture of the wonderful story of salvation. The great commandment of love isn’t about some altruistic humanistic project – us saving the world. Reaching out to others, especially to those who labour under the heavy load of toil and suffering, is not just an act of goodness. It is a participation in the economy of God’s salvation – God saving the world through us and in spite of us. We can love only because we have been loved. We can only heal because we have been healed and continue to be healed by the Good Samaritan Himself, Jesus Christ. To understand what it means to love, does not mean attempting to be a ‘Good Samaritan.’ To understand what it means to love, we need to gaze upon Jesus Christ, He is the ‘Good Samaritan’ who has laid down His life and atoned for our sins. This is eternal life!

Labels:

creation,

Good Samaritan,

parable,

redemption,

salvation,

Sin,

Sunday Homily

Saturday, April 26, 2025

Call to Conversion

Third Sunday of Easter Year C

Pilgrimage Day 7 - Basilica of St Ignatius (Chapel of Conversion)

The theme of conversion rings within these walls. An attic was converted into a hospital room, a tormented fallen soldier is converted into a saint, or at least the beginning of one. Dreams of valour were converted into a new zeal for Christ. A mercenary soldier was converted into a missionary and charismatic reformer of the Church.

In this room, with its dark wooden beams and leaden windows, Ignatius of Loyola recovered from his grisly wounds received at the battle of Pamplona. Spirit beaten, body shattered, leg broken and mended horribly, leaving him crippled for the rest of his life, Ignatius of Loyola hovered near death for months, crying out against the cruel fate that saw his dreams of glory and honour at court all-but-extinguished. Sitting in the musty silence, the occasional creak of the centuries-old floor the only accompaniment, you can almost hear his anguished screams of pain and despair, the hushed footsteps of doctors and attendants rushing about to save his life, a life that he no longer recognised. His life would have been quite different if his body and pride had not been broken. Perhaps strength doesn't reside in having never been broken, but in the courage required to grow strong in the broken places. As surgeons would tell you, that where a bone is broken and heals, it becomes the strongest part of the bone.

Our gospel for this Sunday, also provides us with another living testimony of this truth - that we do grow stronger in grace in places where we have been broken by sin. The gospel provides us with the post end-credits of the Gospel of John, where we see a disillusioned Peter, who has abandoned his mission and vocation to return to his earlier profession, being brought to life once again by the Risen Lord. Our Lord could have gone in search of fresh candidates to continue His mission of building and tending His Church but instead chooses to return to the one who had denied Him, abandoned Him and who even now leads others astray by guiding them to return to the work of being fishers of fish rather than of men.

Both stories, that of Peter’s and Ignatius’, provide us with some important insights into the process and anatomy of conversion.

Firstly, conversion is an invitation given by our Lord to all. It’s much easier for us to think that conversion is for some, but not us. The sinner, the unbeliever, the lapsed Catholic, the one who has betrayed and hurt us - they need conversion. But not us. Heaven forbid. But conversion is a constant ever-developing process of us growing closer to the Lord. It is a call to repentance, because everyone of us are sinners. It is a call to sanctification because none of us are finished products, just work in progress. In this chapel, Ignatius experienced a conversion but it wasn’t his last experience, just the first. Likewise, though Peter seemed to have been “resurrected” and restored to his mission and vocation, scripture and tradition tells us of other instances where he would falter again, needing a wake-up call to return to his original vocation.

Secondly, the reason why the Lord calls us to conversion is because He loves us. So often we have bought into the lie that to call someone to conversion is being judgmental and unloving. In the West, conversion therapy, that is helping someone deal with delusions as regard to their sexuality, is considered a form of hate crime. But this couldn’t be further from the truth. It is precisely God’s terrific love for us that leads to the call to change, to conversion, to metanoia. God does not love us because we are already so good. Instead, He loves us in order to make us good, to bring us back to the goodness that was originally meant for us but that we have lost.

Thirdly, there is no conversion without a crisis. The Chinese term for crisis is made up of two characters – one character means danger or risk and the other, opportunity. Every crisis, therefore, is an opportunity for good, for transformative change, for strengthening of our resolve and character. So, rather than regard a crisis as a cruel curse imposed on us by a capricious God, we should view every crisis as a signpost sent by God to help us make the proper correction before it is too late. It could be as dramatic as a crisis which ends a career or a dream as in the case of Ignatius, or death of a mentor as in the case of Peter. When crisis hits, we have a choice. We can choose the path of resentment or we can choose the path of renewal.

We have passed the midway point of our pilgrimage but have we seen the change, transformation and conversion needed to complete the rest of the journey and beyond? Just like Peter, many of us may have lost sight of our calling, our initial fervour. Peter had lost sight of what Christ had originally spoken over him; that on him, the Rock, the Lord would build His church. We have lost sight of what happened at our baptism, we became living stones which are to be built into a spiritual house for a holy priesthood to offer spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ. Failure, disillusionment and forgetfulness comes to us all. But our Lord shows us that in the resurrection, and because of the resurrection, restoration is possible. The resurrection reminds us that faith can emerge from the ashes of doubt, as life breaks forth from the prison of death. This is the foundation of our Christian hope.

The problem with many of us is that we seem to express greater faith in the severity of our brokenness than in the grace of God to restore us to wholeness. Many are afraid to look into the piercing eyes of our Lord, for fear that they may see judgment. Others believe that there is no getting up from the royal tumble down the ladder of perfection and the only option would be to stay down, stay safe, instead of getting up and risk being hit by the bullets of criticism and ridicule. But the story of Ignatius’ conversion and Peter’s restoration remind us that failure need not be the ending written for life’s script. Perhaps, if we have the courage, the hope and the faith to peer into those tender eyes of our Merciful Lord, we would catch sight of something quite different, something that would surprise us – an invitation to surrender all to Him, our heavy baggage, our burdened conscience and our broken and wounded past.

Above the altar, on one of the great beams is an inscription, both in Basque and Spanish, which translates as: “Here, Ignatius of Loyola surrendered to God”. Truly, it is surrender that this room demands. As we enter this room we too are asked - just as was Ignatius - to be prepared to surrender: to be converted, to let expectations fall away and see not just ourselves and our own needs, but the needs of the Church. Centuries ago, this room was the place where a broken, despondent St Ignatius answered God’s call to set the world on fire. And centuries before that on the shores of the lake of Galilee, our first Pope gazed into the charcoal fire and received a challenge from the Lord to rekindle the fire of mission in his heart. Their conversion led to the conversion of many in the world. Today, from this room let us go forth to keep that fire burning so that the Church and the world may be set ablaze with God’s love.

Pilgrimage Day 7 - Basilica of St Ignatius (Chapel of Conversion)

The theme of conversion rings within these walls. An attic was converted into a hospital room, a tormented fallen soldier is converted into a saint, or at least the beginning of one. Dreams of valour were converted into a new zeal for Christ. A mercenary soldier was converted into a missionary and charismatic reformer of the Church.

In this room, with its dark wooden beams and leaden windows, Ignatius of Loyola recovered from his grisly wounds received at the battle of Pamplona. Spirit beaten, body shattered, leg broken and mended horribly, leaving him crippled for the rest of his life, Ignatius of Loyola hovered near death for months, crying out against the cruel fate that saw his dreams of glory and honour at court all-but-extinguished. Sitting in the musty silence, the occasional creak of the centuries-old floor the only accompaniment, you can almost hear his anguished screams of pain and despair, the hushed footsteps of doctors and attendants rushing about to save his life, a life that he no longer recognised. His life would have been quite different if his body and pride had not been broken. Perhaps strength doesn't reside in having never been broken, but in the courage required to grow strong in the broken places. As surgeons would tell you, that where a bone is broken and heals, it becomes the strongest part of the bone.

Our gospel for this Sunday, also provides us with another living testimony of this truth - that we do grow stronger in grace in places where we have been broken by sin. The gospel provides us with the post end-credits of the Gospel of John, where we see a disillusioned Peter, who has abandoned his mission and vocation to return to his earlier profession, being brought to life once again by the Risen Lord. Our Lord could have gone in search of fresh candidates to continue His mission of building and tending His Church but instead chooses to return to the one who had denied Him, abandoned Him and who even now leads others astray by guiding them to return to the work of being fishers of fish rather than of men.

Both stories, that of Peter’s and Ignatius’, provide us with some important insights into the process and anatomy of conversion.

Firstly, conversion is an invitation given by our Lord to all. It’s much easier for us to think that conversion is for some, but not us. The sinner, the unbeliever, the lapsed Catholic, the one who has betrayed and hurt us - they need conversion. But not us. Heaven forbid. But conversion is a constant ever-developing process of us growing closer to the Lord. It is a call to repentance, because everyone of us are sinners. It is a call to sanctification because none of us are finished products, just work in progress. In this chapel, Ignatius experienced a conversion but it wasn’t his last experience, just the first. Likewise, though Peter seemed to have been “resurrected” and restored to his mission and vocation, scripture and tradition tells us of other instances where he would falter again, needing a wake-up call to return to his original vocation.

Secondly, the reason why the Lord calls us to conversion is because He loves us. So often we have bought into the lie that to call someone to conversion is being judgmental and unloving. In the West, conversion therapy, that is helping someone deal with delusions as regard to their sexuality, is considered a form of hate crime. But this couldn’t be further from the truth. It is precisely God’s terrific love for us that leads to the call to change, to conversion, to metanoia. God does not love us because we are already so good. Instead, He loves us in order to make us good, to bring us back to the goodness that was originally meant for us but that we have lost.

Thirdly, there is no conversion without a crisis. The Chinese term for crisis is made up of two characters – one character means danger or risk and the other, opportunity. Every crisis, therefore, is an opportunity for good, for transformative change, for strengthening of our resolve and character. So, rather than regard a crisis as a cruel curse imposed on us by a capricious God, we should view every crisis as a signpost sent by God to help us make the proper correction before it is too late. It could be as dramatic as a crisis which ends a career or a dream as in the case of Ignatius, or death of a mentor as in the case of Peter. When crisis hits, we have a choice. We can choose the path of resentment or we can choose the path of renewal.

We have passed the midway point of our pilgrimage but have we seen the change, transformation and conversion needed to complete the rest of the journey and beyond? Just like Peter, many of us may have lost sight of our calling, our initial fervour. Peter had lost sight of what Christ had originally spoken over him; that on him, the Rock, the Lord would build His church. We have lost sight of what happened at our baptism, we became living stones which are to be built into a spiritual house for a holy priesthood to offer spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ. Failure, disillusionment and forgetfulness comes to us all. But our Lord shows us that in the resurrection, and because of the resurrection, restoration is possible. The resurrection reminds us that faith can emerge from the ashes of doubt, as life breaks forth from the prison of death. This is the foundation of our Christian hope.

The problem with many of us is that we seem to express greater faith in the severity of our brokenness than in the grace of God to restore us to wholeness. Many are afraid to look into the piercing eyes of our Lord, for fear that they may see judgment. Others believe that there is no getting up from the royal tumble down the ladder of perfection and the only option would be to stay down, stay safe, instead of getting up and risk being hit by the bullets of criticism and ridicule. But the story of Ignatius’ conversion and Peter’s restoration remind us that failure need not be the ending written for life’s script. Perhaps, if we have the courage, the hope and the faith to peer into those tender eyes of our Merciful Lord, we would catch sight of something quite different, something that would surprise us – an invitation to surrender all to Him, our heavy baggage, our burdened conscience and our broken and wounded past.

Above the altar, on one of the great beams is an inscription, both in Basque and Spanish, which translates as: “Here, Ignatius of Loyola surrendered to God”. Truly, it is surrender that this room demands. As we enter this room we too are asked - just as was Ignatius - to be prepared to surrender: to be converted, to let expectations fall away and see not just ourselves and our own needs, but the needs of the Church. Centuries ago, this room was the place where a broken, despondent St Ignatius answered God’s call to set the world on fire. And centuries before that on the shores of the lake of Galilee, our first Pope gazed into the charcoal fire and received a challenge from the Lord to rekindle the fire of mission in his heart. Their conversion led to the conversion of many in the world. Today, from this room let us go forth to keep that fire burning so that the Church and the world may be set ablaze with God’s love.

Labels:

conversion,

Easter,

pilgrimage homily,

Providence,

Repentance,

saints,

Sin,

Suffering,

Sunday Homily,

Vocations

Tuesday, April 22, 2025

As Newborn Babes

Second Sunday of Easter

Divine Mercy Sunday

It can be a real challenge to wrap your head around the fact that this Sunday goes by many names. Some would argue – way too many. Today is the Second Sunday of Easter but it is also known as the Sunday within the Octave of Easter. In the extraordinary form and in the pre-1969 calendar, it was also called Low Sunday (in relation to last Sunday, Easter). And since the pontificate of St John Paul II, it has received this eponymous title - Divine Mercy Sunday. As we continue to pray for Pope Francis of happy memory, we too remember how mercy had been one of the major lietmotifs of his pontificate.

But my favourite name for this Sunday is derived from the incipit of the entrance antiphon for this Sunday. Quasimodo Sunday. It is taken from 1 Peter 2:2 and in Latin, it begins with these words: “quasi modo geniti infantes” or in English, “like newborn infants.” This is the full text of the antiphon: “As newborn babes, desire the rational milk without guile, that thereby you may grow unto salvation: If so, be you have tasted that the Lord is sweet.”

The name Quasimodo Sunday may not be familiar to many of you, but the name is not unfamiliar. Sounds like an oxymoron, right? Well, if you recall Victor Hugo’s novel, “The Hunchback of Notre Dame,” (or the Disney animated version) you will remember that the main protagonist’s name is Quasimodo, the eponymous Hunchback of the story. For those not familiar with the storyline, this tale of love, chivalry and strange beauty is about this unlikely hero, the severely deformed hunchback, with a pristinely beautiful and innocent heart and soul, who lived in the rafters of Paris’ famous Cathedral of Notre Dame.

In Hugo’s novel, Quasimodo, rejected by his parents for his deformities, is abandoned inside Notre Dame Cathedral, at a place where orphans and unwanted children were dropped off. Monseigneur Claude Frollo, the Archdeacon, finds the child on “Quasimodo Sunday” and “called him Quasimodo; whether it was that he chose thereby to commemorate the day when he had found him, or that he meant to mark by that name how incomplete and imperfectly moulded the poor little creature was,” Hugo wrote.

In a strange way, the character Quasimodo, who risked his own life to save another whom he loves, is a type of Christ. And like Quasimodo, Christ also appears before His disciples today, arrayed not in gold and resplendent garments, but carrying the trophies of His victory on the cross - His wounds, His deformities. But unlike Quasimodo, our Lord was not born with these deformities, for He is the unblemished Paschal Lamb. These are the scars of the torture He endured for our sake. Instead of an unscarred and unblemished appearance, He chooses to retain His ugly wounds as a sign, not of His failure, but of His victory over sin and death. His wounds are supremely beautiful because they are visible marks of His love for us, the receipt for the price He had paid for us, the booty of a cosmic battle which He had fought and won for us.

Yes, in a way, all of us are incomplete and imperfectly moulded. We desire and hunger for the sacramental milk which only our Mother, the Church, can give. We have been deformed by sin, poor orphans abandoned and languishing in this Valley of Tears, waiting to be picked up by our Heavenly Father and to be adopted by Him. In His mercy, He has given us His only begotten Son, the Divine Mercy, not only to be our companion but to exchange places with us. Our Lord Jesus, the sinless and perfect Son of God, Beauty ever ancient ever new, chose to take our ugliness upon Himself in order to confer upon us the beauty of sanctifying grace. He took our sentence of death, in order to grant us the repeal of life. He has done this through the Sacraments of Baptism and the Eucharist, symbolised by the water and blood which flowed out through His wounded side, the source being His Most Sacred Heart beating in love for us.

But St Faustina also saw in that gushing spring of water and blood something else - grace and mercy. This is what she wrote: “All grace flows from mercy, and the last hour abounds with mercy for us. Let no one doubt concerning the goodness of God; even if a person’s sins were as dark as night, God’s mercy is stronger than our misery.” (Diary of St. Faustina, number 1507) Even the ugliest Quasimodos in this world can be potentially the most beautiful beings seen through the lenses of grace and mercy because “God’s mercy is stronger than misery!”

In Victor Hugo’s novel, as a group of old women hunkered over to examine the little monstrosity that had been left near the vestibule of the Cathedral, one of them remarked, “I'm not learned in the matter of children ...but it must be a sin to look at this one." Could this remark be referring to us too? This is who we were, inheritors of Original Sin, prisoners and victims of our own sinful misdeeds, deformed by our iniquities, that it would be a sin for anyone to look at us. But then, God looked upon us, not with vile disgust or hatred but with love and mercy, and His “mercy is stronger than misery.” God offered us atonement and pardon for our sins. God offered us His incalculable mercy by offering us His son to take our place on the cross. As Saint Paul assures us, “God made Him who had no sin to be sin for us, so that in Him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Cor 5:21). We have seen this God, we have tasted Him, we have been redeemed and saved through His grace and mercy, and we can proudly acclaim that we have tasted the Lord and can testify that He is sweet!

Divine Mercy Sunday

It can be a real challenge to wrap your head around the fact that this Sunday goes by many names. Some would argue – way too many. Today is the Second Sunday of Easter but it is also known as the Sunday within the Octave of Easter. In the extraordinary form and in the pre-1969 calendar, it was also called Low Sunday (in relation to last Sunday, Easter). And since the pontificate of St John Paul II, it has received this eponymous title - Divine Mercy Sunday. As we continue to pray for Pope Francis of happy memory, we too remember how mercy had been one of the major lietmotifs of his pontificate.

But my favourite name for this Sunday is derived from the incipit of the entrance antiphon for this Sunday. Quasimodo Sunday. It is taken from 1 Peter 2:2 and in Latin, it begins with these words: “quasi modo geniti infantes” or in English, “like newborn infants.” This is the full text of the antiphon: “As newborn babes, desire the rational milk without guile, that thereby you may grow unto salvation: If so, be you have tasted that the Lord is sweet.”

The name Quasimodo Sunday may not be familiar to many of you, but the name is not unfamiliar. Sounds like an oxymoron, right? Well, if you recall Victor Hugo’s novel, “The Hunchback of Notre Dame,” (or the Disney animated version) you will remember that the main protagonist’s name is Quasimodo, the eponymous Hunchback of the story. For those not familiar with the storyline, this tale of love, chivalry and strange beauty is about this unlikely hero, the severely deformed hunchback, with a pristinely beautiful and innocent heart and soul, who lived in the rafters of Paris’ famous Cathedral of Notre Dame.

In Hugo’s novel, Quasimodo, rejected by his parents for his deformities, is abandoned inside Notre Dame Cathedral, at a place where orphans and unwanted children were dropped off. Monseigneur Claude Frollo, the Archdeacon, finds the child on “Quasimodo Sunday” and “called him Quasimodo; whether it was that he chose thereby to commemorate the day when he had found him, or that he meant to mark by that name how incomplete and imperfectly moulded the poor little creature was,” Hugo wrote.

In a strange way, the character Quasimodo, who risked his own life to save another whom he loves, is a type of Christ. And like Quasimodo, Christ also appears before His disciples today, arrayed not in gold and resplendent garments, but carrying the trophies of His victory on the cross - His wounds, His deformities. But unlike Quasimodo, our Lord was not born with these deformities, for He is the unblemished Paschal Lamb. These are the scars of the torture He endured for our sake. Instead of an unscarred and unblemished appearance, He chooses to retain His ugly wounds as a sign, not of His failure, but of His victory over sin and death. His wounds are supremely beautiful because they are visible marks of His love for us, the receipt for the price He had paid for us, the booty of a cosmic battle which He had fought and won for us.

Yes, in a way, all of us are incomplete and imperfectly moulded. We desire and hunger for the sacramental milk which only our Mother, the Church, can give. We have been deformed by sin, poor orphans abandoned and languishing in this Valley of Tears, waiting to be picked up by our Heavenly Father and to be adopted by Him. In His mercy, He has given us His only begotten Son, the Divine Mercy, not only to be our companion but to exchange places with us. Our Lord Jesus, the sinless and perfect Son of God, Beauty ever ancient ever new, chose to take our ugliness upon Himself in order to confer upon us the beauty of sanctifying grace. He took our sentence of death, in order to grant us the repeal of life. He has done this through the Sacraments of Baptism and the Eucharist, symbolised by the water and blood which flowed out through His wounded side, the source being His Most Sacred Heart beating in love for us.

But St Faustina also saw in that gushing spring of water and blood something else - grace and mercy. This is what she wrote: “All grace flows from mercy, and the last hour abounds with mercy for us. Let no one doubt concerning the goodness of God; even if a person’s sins were as dark as night, God’s mercy is stronger than our misery.” (Diary of St. Faustina, number 1507) Even the ugliest Quasimodos in this world can be potentially the most beautiful beings seen through the lenses of grace and mercy because “God’s mercy is stronger than misery!”

In Victor Hugo’s novel, as a group of old women hunkered over to examine the little monstrosity that had been left near the vestibule of the Cathedral, one of them remarked, “I'm not learned in the matter of children ...but it must be a sin to look at this one." Could this remark be referring to us too? This is who we were, inheritors of Original Sin, prisoners and victims of our own sinful misdeeds, deformed by our iniquities, that it would be a sin for anyone to look at us. But then, God looked upon us, not with vile disgust or hatred but with love and mercy, and His “mercy is stronger than misery.” God offered us atonement and pardon for our sins. God offered us His incalculable mercy by offering us His son to take our place on the cross. As Saint Paul assures us, “God made Him who had no sin to be sin for us, so that in Him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Cor 5:21). We have seen this God, we have tasted Him, we have been redeemed and saved through His grace and mercy, and we can proudly acclaim that we have tasted the Lord and can testify that He is sweet!

Labels:

Divine Mercy,

Easter,

Feast,

Feast Day Homily,

Mercy,

redemption,

Resurrection,

salvation,

Sin,

Sunday Homily

Monday, April 14, 2025

The Towel and the Cross

Maundy Thursday

Some people are so good at talking big but fall short in delivery. When push comes to shove, they will easily bend and break. This is what we witness in the gospel. Our first Pope whom the Lord Himself declares as a rock-hard foundation to His church, changes his position not because of some profound enlightenment but melts under pressure. One can’t help but laugh at the 180 degrees turn of St Peter, from refusing to accept the Lord’s offer to wash his feet, to clamouring for a full-body bath!

First, he starts with this: “You shall never wash my feet.” We may even suspect that his refusal was just fake shocked indignation at best, or false humility at worst. And as for the turnaround, doesn’t it seem to be some form of histrionic over-exaggeration on his part? “Not only my feet, but my hands and my head as well!” In both instances, St Peter had misunderstood our Lord’s intention and the significance of His action. And in both instances, his incomprehension and misstep had given our Lord an opportunity to make a teaching point.

Let us look at the first response given by our Lord to Peter when he refused to allow his feet to be washed: “If I do not wash you, you can have nothing in common with me.” A superficial reading of this statement may lead us to conclude that our Lord was just asking Peter and all of us to imitate His humility in serving others. This may be the message at the end of the passage, where our Lord says: “If I, then, the Lord and Master, have washed your feet, you should wash each other’s feet. I have given you an example so that you may copy what I have done to you.” But the words of our Lord in His response to Peter’s refusal to have his feet washed, goes further than that.

What is this thing which makes us “in common” with our Lord? In other words, what does it mean to have “fellowship” with Him? It is clear that it cannot just mean menial service, but rather the sacrifice of our Lord on the cross. This statement actually highlights the relationship between the foot-washing and the cross. The foot-washing signifies our Lord’s loving action and sacrifice on the cross. If foot-washing merely cleans the feet of the guest who has come in from the dusty streets, our Lord’s sacrifice on the cross will accomplish the cleansing of our sins which we have accumulated from our sojourn in this sin-infested world. Peter must yield to our Lord’s loving action in order to share in His life, which the cross makes possible.

The foot-washing may also be a deliberate echo of the ritual of ablutions, washing of hands and feet, done by the priests of the Old Covenant, before they performed worship and offered sacrifices in the Temple. This may explain Peter’s further request to have both his feet and head washed by the Lord. Without him knowing it, he may have inadvertently referred to his own ordination as a priest of the New Covenant. It is fitting that the washing of feet occurs while the Apostles are entrusted with the Eucharist. No priesthood, no Eucharist - it’s as simple as that.

“No one who has taken a bath needs washing, he is clean all over.” Our Lord was not just making a common-sense statement that those who are clean have no need for further cleansing, but an allusion to the Sacraments which leave an indelible mark on their recipients, two in particular - baptism (confirmation) and Holy Orders. Our Lord’s words resonate with two popular Catholic axioms: “Once a Catholic, always a Catholic” and “once a priest, always a priest.” There is no need for re-baptism or re-ordination even if the person had lapsed. What is needed is confession.

This second set of words also points to the efficacy and sufficiency of what our Lord did on the cross. Christ’s bloody sacrifice on Calvary took place once and for all, and it will never be repeated, it need not be repeated because it cannot be repeated. To repeat His sacrifice would be to imply that the original offering was defective or insufficient, like the animal sacrifices of the Old Testament that could never take away sins. Jesus’ offering was perfect, efficacious, and eternal.

The Holy Mass is a participation in this one perfect offering of Christ on the cross. It is the re-presentation of the sacrifice on the cross; here “re-presentation” does not mean a mere commemoration or a fresh new sacrifice each time the Mass is celebrated, but making “present” the one sacrifice at Calvary. The Risen Christ becomes present on the altar and offers Himself to God as a living sacrifice. Like the Mass, Christ words at the Last Supper are words of sacrifice, “This is my body . . . this is my blood . . . given up for you.” So, the Mass is not repeating the murder of Jesus, but is taking part in what never ends: the offering of Christ to the Father for our sake (Heb 7:25, 9:24). After all, if Calvary didn’t get the job done, then the Mass won’t help. It is precisely because the death of Christ was sufficient that the Mass is celebrated. It does not add to or take away, from the work of Christ—it IS the work of Christ.

When the Lord tells us: “I have given you an example so that you may copy what I have done to you,” it is not just the ritual of foot-washing that He is asking us to imitate. Our Lord is most certainly pointing to His work of salvation on the cross which He offers to us as a gift through the Sacraments. Some people continue to resist Christ because they do not consider themselves sinful enough to require Him to wash them in Baptism or the Sacrament of Penance. Others have the opposite problem: they stay away because they are too ashamed of their lives or secret sins. To both, our Lord and Master gently but firmly speaks these words as He did to Peter: “If I do not wash you, you can have nothing in common with me.”

Some people are so good at talking big but fall short in delivery. When push comes to shove, they will easily bend and break. This is what we witness in the gospel. Our first Pope whom the Lord Himself declares as a rock-hard foundation to His church, changes his position not because of some profound enlightenment but melts under pressure. One can’t help but laugh at the 180 degrees turn of St Peter, from refusing to accept the Lord’s offer to wash his feet, to clamouring for a full-body bath!

First, he starts with this: “You shall never wash my feet.” We may even suspect that his refusal was just fake shocked indignation at best, or false humility at worst. And as for the turnaround, doesn’t it seem to be some form of histrionic over-exaggeration on his part? “Not only my feet, but my hands and my head as well!” In both instances, St Peter had misunderstood our Lord’s intention and the significance of His action. And in both instances, his incomprehension and misstep had given our Lord an opportunity to make a teaching point.

Let us look at the first response given by our Lord to Peter when he refused to allow his feet to be washed: “If I do not wash you, you can have nothing in common with me.” A superficial reading of this statement may lead us to conclude that our Lord was just asking Peter and all of us to imitate His humility in serving others. This may be the message at the end of the passage, where our Lord says: “If I, then, the Lord and Master, have washed your feet, you should wash each other’s feet. I have given you an example so that you may copy what I have done to you.” But the words of our Lord in His response to Peter’s refusal to have his feet washed, goes further than that.

What is this thing which makes us “in common” with our Lord? In other words, what does it mean to have “fellowship” with Him? It is clear that it cannot just mean menial service, but rather the sacrifice of our Lord on the cross. This statement actually highlights the relationship between the foot-washing and the cross. The foot-washing signifies our Lord’s loving action and sacrifice on the cross. If foot-washing merely cleans the feet of the guest who has come in from the dusty streets, our Lord’s sacrifice on the cross will accomplish the cleansing of our sins which we have accumulated from our sojourn in this sin-infested world. Peter must yield to our Lord’s loving action in order to share in His life, which the cross makes possible.

The foot-washing may also be a deliberate echo of the ritual of ablutions, washing of hands and feet, done by the priests of the Old Covenant, before they performed worship and offered sacrifices in the Temple. This may explain Peter’s further request to have both his feet and head washed by the Lord. Without him knowing it, he may have inadvertently referred to his own ordination as a priest of the New Covenant. It is fitting that the washing of feet occurs while the Apostles are entrusted with the Eucharist. No priesthood, no Eucharist - it’s as simple as that.

“No one who has taken a bath needs washing, he is clean all over.” Our Lord was not just making a common-sense statement that those who are clean have no need for further cleansing, but an allusion to the Sacraments which leave an indelible mark on their recipients, two in particular - baptism (confirmation) and Holy Orders. Our Lord’s words resonate with two popular Catholic axioms: “Once a Catholic, always a Catholic” and “once a priest, always a priest.” There is no need for re-baptism or re-ordination even if the person had lapsed. What is needed is confession.

This second set of words also points to the efficacy and sufficiency of what our Lord did on the cross. Christ’s bloody sacrifice on Calvary took place once and for all, and it will never be repeated, it need not be repeated because it cannot be repeated. To repeat His sacrifice would be to imply that the original offering was defective or insufficient, like the animal sacrifices of the Old Testament that could never take away sins. Jesus’ offering was perfect, efficacious, and eternal.

The Holy Mass is a participation in this one perfect offering of Christ on the cross. It is the re-presentation of the sacrifice on the cross; here “re-presentation” does not mean a mere commemoration or a fresh new sacrifice each time the Mass is celebrated, but making “present” the one sacrifice at Calvary. The Risen Christ becomes present on the altar and offers Himself to God as a living sacrifice. Like the Mass, Christ words at the Last Supper are words of sacrifice, “This is my body . . . this is my blood . . . given up for you.” So, the Mass is not repeating the murder of Jesus, but is taking part in what never ends: the offering of Christ to the Father for our sake (Heb 7:25, 9:24). After all, if Calvary didn’t get the job done, then the Mass won’t help. It is precisely because the death of Christ was sufficient that the Mass is celebrated. It does not add to or take away, from the work of Christ—it IS the work of Christ.

When the Lord tells us: “I have given you an example so that you may copy what I have done to you,” it is not just the ritual of foot-washing that He is asking us to imitate. Our Lord is most certainly pointing to His work of salvation on the cross which He offers to us as a gift through the Sacraments. Some people continue to resist Christ because they do not consider themselves sinful enough to require Him to wash them in Baptism or the Sacrament of Penance. Others have the opposite problem: they stay away because they are too ashamed of their lives or secret sins. To both, our Lord and Master gently but firmly speaks these words as He did to Peter: “If I do not wash you, you can have nothing in common with me.”

Labels:

confession,

Cross,

Discipleship,

Feast,

Feast Day Homily,

Holy Thursday,

Holy Week,

Lent,

Paschal Triduum,

Priesthood,

Sacraments,

Sacrifice,

Sin

Sunday, March 30, 2025

Every Saint has a past; every sinner a future

Fifth Sunday of Lent Year C

There is a clever quote that is often attributed to the Buddha, “Do not dwell in the past, do not dream of the future, concentrate the mind on the present moment." If you do not have a pedantic nature like me, you will most likely take this as gospel truth. The problem is, it’s a fake quote. The Buddha didn’t say this. He said something similar but yet fundamentally different from what the above quote claims. In fact, the Buddha had also asked us to let go of the present - no past, no future, no present.

The Christian version of this quote may sound like this, “don’t dwell on the past, but move forward.” Unlike the above quote, this is founded on scripture, especially the readings we have just heard today.

Most of us would take the above saying as referring to not holding on to painful memories, failures, and past hurts. That is clear. Some people are trapped in the past, in a cycle of regret, resentment, un-forgiveness and despair. Past painful memories keep on re-playing in their minds like a broken record, re-igniting the sense of pain and loss as if the incident had just happened a moment ago. Any counsellor or psychologist or a good friend or relative will tell you, “Best to keep the past in the past. Move on. Learn from it. If you dwell in the past, you will get left behind.”

But our readings bring up additional lessons on why we should not dwell on the past but seek to move forward.

In the first reading, Isaiah writes to a people who are now languishing in exile, regretting their past misdeeds and wallowing in self-pity and despair. Isaiah’s message does not entirely erase the past. He reminds his people of how God had also liberated their ancestors from Egypt during the Exodus and even performed this impossible miracle of leading them through the Red Sea whilst destroying the army of a superpower in pursuit. It was important to remember this less the Jews in exile were to doubt Isaiah’s prophecy that God was going to bring them home and rebuild their nation. But it was also important that the Jews did not feel trapped in the past of their failures and miss out on what God is going to reveal and do in their lives. And so, Isaiah tells them: “No need to recall the past, no need to think about what was done before. See, I am doing a new deed, even now it comes to light; can you not see it? Yes, I am making a road in the wilderness, paths in the wilds.”